Nika Levikov virtually sits down with Dr Sandro Lanfranco to understand what it means to be human, how our understanding of humanity has changed over time, and whether any of it matters.

Continue readingVoices for freedom and choice

Author: Dr Alexander Clayman

Abortion is a criminal offence in Malta. This means Maltese women who wish to end their pregnancy have severely limited choices. Those more affluent can pay to terminate their pregnancy abroad. Those who do not have the money can either continue the pregnancy against their will or terminate locally under unsafe conditions, risking both their health and freedom.

Any woman who undertakes an abortion potentially faces three years in jail. Anybody who assists, such as a doctor, could also be sentenced to four years behind bars. This flies in the face of best medical practice which states that safe abortion services should be accessible to women who need them.

A few weeks ago a group of doctors, including myself, came together to set up Doctors for Choice Malta in order to advocate for sexual and reproductive health. This includes comprehensive sex education (NOT abstinence-only education) and access to free contraception (condoms, pills, and intrauterine devices). Increased use of contraception alone results in fewer unwanted pregnancies and subsequent abortions. Putting contraceptives in the hands of comprehensively sex-educated individuals can do even more. This said, abortion still needs to be available to those people who need it.

As a doctor, I feel I have a duty to use my knowledge and skills to better my community’s health. Together with Doctors for Choice, we are basing our efforts not on opinions or morality, but on years of medical and sociological research which shows that sex education, contraception, and accessible abortions make a society healthier.

The irony was not lost on me when comments accusing me of being a baby-killing-mad-axe-murderer-who-doesn’t-understand-what-a-real-doctor-is started rolling in. Luckily for me, forewarned is forearmed, and the negativity failed to penetrate very deep.

What did strike me was the contrast between the way people communicate their derision and their support. Abusive comments come in fast, prominent, and loud. Supportive comments are usually sent in private. At present, it’s clearly very easy to be openly anti-choice, but very difficult to be openly pro-choice.

To those afraid to raise their voice and speak the truth, I say: whatever dogma, tradition, or a battalion of angry keyboard lieutenants might tell us, those who advocate for reproductive choice have nothing to be ashamed of. We are on the right side of history.

Read more: Marston, C., & Cleland, J. (2003). Relationships between Contraception and Abortion: A Review of the Evidence. International Family Planning Perspectives, 29(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.2307/3180995

Stanger-Hall, K. F., & Hall, D. W. (2011). Abstinence-Only Education and Teen Pregnancy Rates: Why We Need Comprehensive Sex Education in the U.S. PLoS ONE, 6(10), e24658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024658

Written in blood

Maltese researchers are leading the way in developing new diagnostic tools for cancer. Dawn Gillies finds out more from Prof. Godfrey Grech and Dr Shawn Baldacchino.

Breast cancer survival rates have been improving steadily in recent years. In Malta, 86.9% of patients currently survive, up 7% over the last decade. Thanks to new targeted therapies, the outlook is increasingly bright. But precision therapies need precision testing.

Breast cancer diagnosis has reached new heights and with current tests using tissue biopsies, pathologists can classify patients for specific treatment. Precision medicine goes a step further. It provides more information, predicting the aggressiveness of the cancer and measuring the number of cells from the tumour that spread into the bloodstream.

This does not mean that all requirements in precision therapy have been met.

At the time of writing, there is no simple method to test patients’ ongoing benefit from treatment or to measure different tumour areas from one sample. For this to be possible, we need super-sensitive tests. This is where Prof. Godfrey Grech and Dr Shawn Baldacchino at the University of Malta come in.

Detecting the undetectable

During his PhD, Baldacchino studied a new class of breast cancer representing most cases of the triple negative type, which affects 12% of breast cancer patients in Malta.

In triple negative breast cancers, tests for estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and excess HER2 protein all result in negatives and are associated with aggressive tumours.

To detect this new class of breast cancer, Grech’s team have created a new test that uses molecular substances we naturally produce in our body—biomarkers. By pinpointing the right combination of certain biomarkers, they can test for this new class within the triple negative breast cancer cases.

They initially used the test to look at biopsies from past patients. These exercises showed that they could accurately detect the cases—even in samples that were over a decade old! In fact, the test was so successful that the team is now working with biological testing industry giant Luminex to use it in hospitals worldwide. With a patent filed, research labs will get their hands on it later this year with the hope that by 2021 it will be used to directly help patients in hospitals.

However, there is more work ahead. Encouraged by the results so far, the team wants to take the test and other current biomarker tests a step further. They want to use a simple blood sample which is less invasive, allowing patients to be monitored during therapy.

Pushing boundaries

With the method Grech and his team have optimised, obtaining information on new classes of patients that predict therapy use, detecting different tumour areas in one sample, and the use of blood to monitor the benefits of therapy have become a

Photo by James Moffett

possible reality. With technologies from Luminex and Thermo Fisher, they can now read over 40 biomarkers in one test simultaneously. But with blood they need a new angle. And that is happening through another test using particles that originate from cells called exosomes.

Exosomes are tiny messenger bubbles which cells release into the blood . ‘We believe that when there is a tumour in the patient, there will be a signature in these exosomes circulating in the blood,’ says Baldacchino.

Finding these exosomes could mean detecting cancer at an earlier stage than is currently possible. The team believes they would be able to detect the exosomes that point to cancer long before a tumour shows up in scans and other regular tests—and so, they would be able to nip the cancer in the bud. But to do this, they need to be able to decode the messages the exosomes are carrying.

Positives for patients

It’s not only in the realm of breast cancer diagnosis and classification that the team can help patients—they might also be able to improve treatment. ‘Most targeted therapies currently try to inhibit specific receptors and proteins to stop the uncontrolled growth of cancer cells,’ Grech says. But through their research, the team has found that targeting the low activity of specific complexes of proteins in tumour cells is key. Their research models show that increasing the activity of these protein complexes is possible using specific drugs.

This is true for triple negative breast cancer, where the amount of PP2A protein is extremely low. The PP2A protein enables the body to fight the cancer, so increasing its activity would create a chain reaction in the body which could limit the growth and spread of that category of cancer cells.

This approach to treatment has applications beyond triple negative breast cancer. Grech is hopeful that PP2A production could be amped up for different types of cancer too, and lead to positive results.

Managing the unmanageable

When organising a project like this, it’s expected that things won’t go to plan. One of the biggest challenges for Grech’s team has been establishing collaborations with other groups across the globe. They need these connections to provide the samples required to test their systems. With other groups working on similar projects, time is a limited resource. Thankfully, the team found collaborators in Leeds (UK), and Barcelona (Spain), allowing the group access to the samples they need.

What is certain is that support for this work has come in many shapes and forms. The project received funding both from public donations and the Malta Council for Science and Technology. Baldacchino also found an ally in the charity foundation Alive with the help of the Research Trust of the University of Malta (RIDT). He is the first recipient of funding from them, and their first graduate.

Predicting the future

Thanks to projects like these, cancer research has a bright future in Malta. The team has their product launch to look forward to later this year, which will see a drastic reduction to the time and effort it takes researchers and doctors to determine the type of breast tumour.

But a lot of challenges lie ahead. The biggest challenge will come in the move to early stage cancers. These cancers have low levels of substances to detect, which means that any test they develop will have to be extremely sensitive in order to be effective. Successfully identifying these cancers would signal a massive breakthrough for the global medical community—and, more importantly, for patients. Early detection through basic blood tests would open the door to early stage treatment and a higher rate of survival. Nothing could matter more.

Project ‘Accurate Cancer Screening Tests‘ financed by the Malta Council for Science & Technology through FUSION: The R&I Technology Development Programme 2016.

A scientist and a linguist board a helicopter…

A scientist and a linguist board a helicopter, and the scientist says to the linguist, ‘What is the cornerstone of civilisation, science or language?’ It might sound like the opening line of a joke, but it’s actually from the opening sequence of the film Arrival (2016). In the film, aliens have landed on our doorstep, and our scientist and linguist have been chosen as suitable emissaries to establish contact. The scientist, perhaps wishing to size up his new colleague, then poses the question. Whose field has been more important to the advancement of the human race? Science or language?

In reality, they are both wrong (or both half-right). It is true that language was necessary for us to organise as a species, forming complex networks of cooperation over vast distances and time. Without specialising our efforts and collaborating, we could not have built our great structures, supported large communities, or migrated over all continents. Yet, without science, without improving our understanding of the natural world, we would still be at its mercy.

Science is the tool we use to change circumstance. When populations are dying from an infectious disease, we create a vaccine. When we’re unable to grow enough food to support ourselves, we develop a better strain of crop. When we struggle to transport materials over great distances, we create machines that will do it for us. Science is our secret weapon, transforming problems into possibilities. However, science alone means little. If innovation dies with its creator, who does it help? Science must be communicated to others before it can make a difference in any meaningful way.

It would be incomplete to bestow language or science with the title of ‘the cornerstone of civilisation.’ It was science communication that really drove our development. And I don’t just mean this in the external sense. After all, is the transfer of genetic information from one generation to the next not science communication? What are we but a biological game of Chinese Whispers, the message mutating through each host but somehow continuing to make sense over millions of years?

The human race not only benefits greatly from science communication; we are the product of it. It is embedded into our biological and cultural history. Proof that it is not just knowledge but the sharing of knowledge that is the real root of power.

Hopefully the aliens agree.

Author: Amanda Mathieson

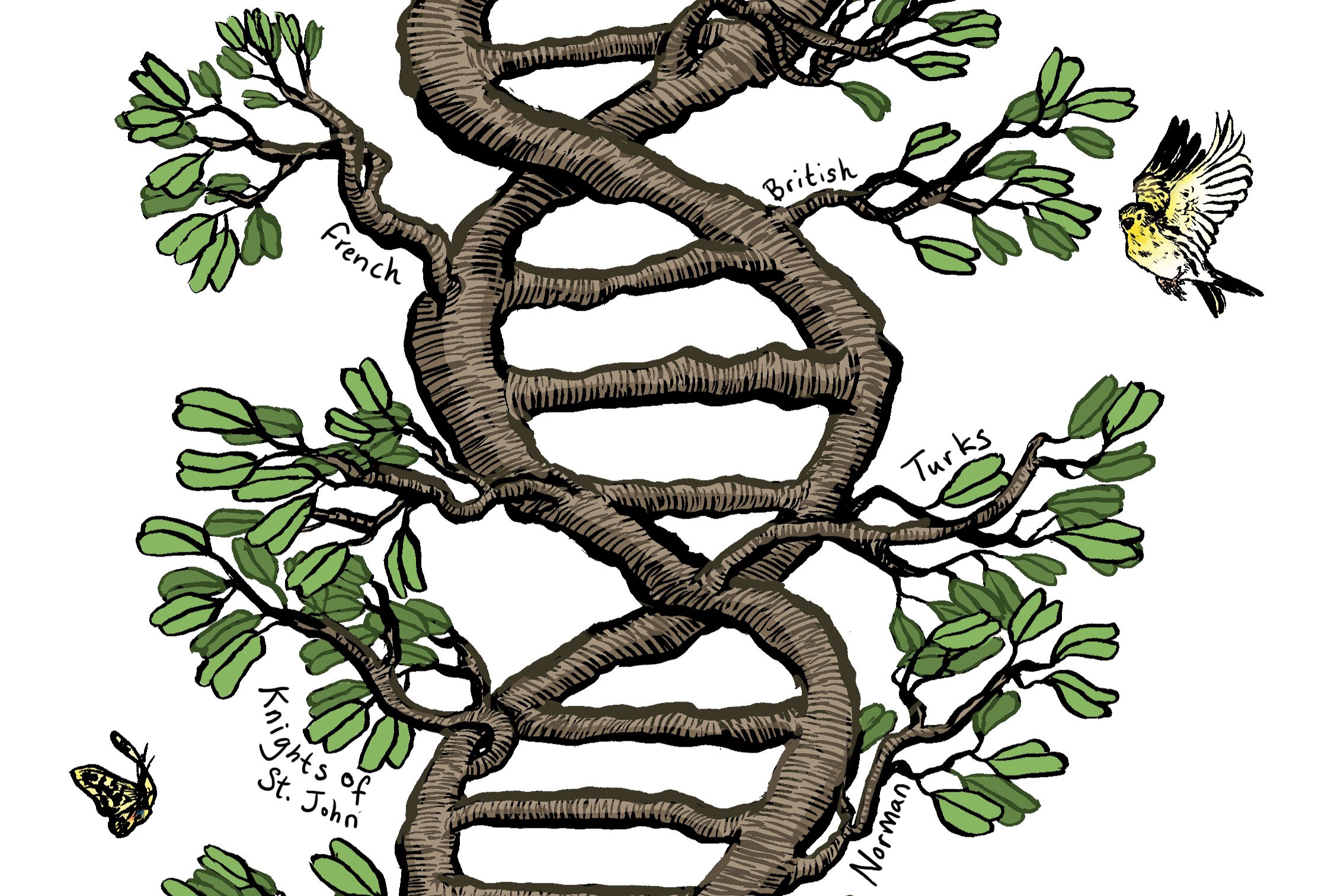

The Hidden History of the Maltese Genome

By reading someone’s DNA one can tell how likely they are to develop a disease or whether they are related to the person sitting next to them. By reading a nation’s DNA one can understand why a population is more likely to develop a disease or how a population came to exist. Scott Wilcockson talks to Prof. Alex Felice, Dr Joseph Borg, and Clint Mizzi (University of Malta) about their latest project that aims to sequence the Maltese genome and what it might reveal about the origins and health of the Maltese people.

Marijuana for Epilepsy

Over the last few decades researchers have been unravelling the truth behind marijuana. Prof. Giuseppe Di Giovanni tells us more about its use in medical research.

Continue reading