Computer, Help Me Play

A Faculty Reborn

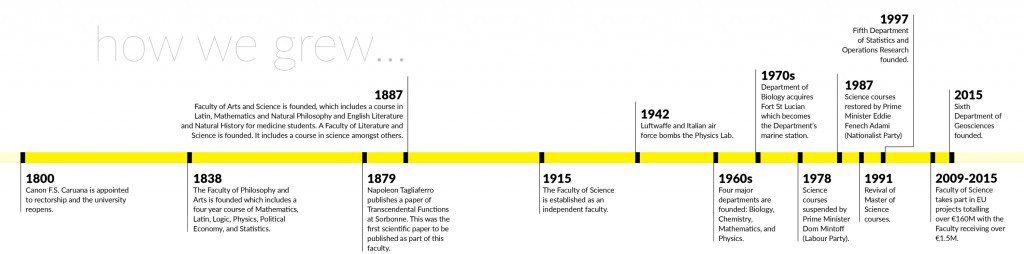

During the mid-1970s, the Faculties of Science and Arts were closed down, and the Bachelor programmes phased out. Most of the foreign (mainly British) academics left Malta, as did some Maltese colleagues. Those few who stayed were assigned teaching duties at the newly established Faculty of Education and Faculty of Engineering. Relatively little research took place, except when funds were unneccessary, and it is thanks to these few that scientific publications kept trickling out.

In 1987, the Faculties of Arts and Science were reconstituted. The Faculty of Science had four ‘divisions’ which became the Departments of Biology, Chemistry, Physics, and Mathematics. In the same year, I returned from the UK to join the Faculty.

Things gradually improved as more staff and students joined. However, equipment was either obsolete or beyond repair. The B.Sc. (Bachelor of Science) course was re-launched with an evening course. Faculty members worked flat out in very poor conditions. The Physics and Mathematics building was still shared with Engineering. Despite these problems, we had a Faculty and identity. Nevertheless, we wanted our courses to be of international repute—our guiding principle.

During the 1990s, yearly budgets had improved slightly along with experimental facilities. Computers and the occasional capital investment helped immensely. Research output increased, as did student numbers, while postgraduate Masters and Ph.D. students started to appear.

Since 2005, some faculty members have been working hard to secure European Regional Development Funds (ERDF) by submitting proposals to reinforce our research infrastructure. A total of six projects were approved with a combined budget of nearly €5 million. This has resulted in new, state of the art research facilities and an exponential increase in research output, bolstered by additional academic staff and research student numbers of close to 80.

Students are now organised and active through S-Cubed, the Science Students’ Society. This leading organisation is one of the three faculty pillars: the academic and support staff, and the student body. Together, we have made giant strides and the future looks bright.

Special thanks to Prof. Stanley Fiorini who helped us compile our timeline, aided by Prof. Josef Lauri.

Treating stone to save Maltese Culture

Malta has three UNESCO world heritage sites which need constant conservation. Generally, it is better to preserve the original building material than replace it. The conservation method called consolidation can glue deteriorating stone material to the underlying healthy stone maintaining it, but few consolidants have been tested on local Globigerina limestone. Sophie Briffa (supervised by Daniel Vella) tested a new set of consolidants which are stronger than other compounds but affected the colour of the stone. She applied five different conditions on the stone. The first three were novel treatments. They were based on a hybrid silane (tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) and 3-(glycidoxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GPTMS)) but one had nanoparticles, one had modified nanoparticles, and the other lacked them. The fourth was a simple laboratory-prepared TEOS silane. The fifth was untreated limestone samples for comparison.

The treatments successfully penetrated the stone’s surface. Microscopy coupled with other techniques including mercury intrusion porosimetry carried out in Cadiz, Spain, confirmed this infiltration and the stone’s physical qualities: strength, drilling resistance, and so on. Half of the treated stones underwent accelerated weathering. The consolidants with nanoparticles or modified nanoparticles were stronger than the other treatments. They also maintained the original surface colour and improved the stones’ ability to absorb water. On the other hand, they were less resistant to salt crystallisation that can damage the stone making it brittle.

The best consolidant for Maltese stone has not yet been found. Ideally, it should have a good penetration and good weathering properties that preserve the stone’s appearance. It should allow ‘breathability’ and be reversible. Current stone consolidation techniques are irreversible since they permanently introduce new material into the stone. These are only acceptable since consolidation is a last attempt to save the stone before complete replacement.

French writer Victor Hugo summed up the importance of this research when he said, ‘Whatever may be the future of architecture, in whatever manner our young architects may one day solve the question of their art, let us, while waiting for new monuments, preserve the ancient monuments. Let us… inspire the nation with a love for national architecture’.

This research was performed as part of an M.Sc. in Mechanical Engineering at the Faculty of Engineering. The research was funded by the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship (Malta).