Why so Serious?

How do you help school children handle fights, bullying, and other conflict properly? You build a game, of course, and you let children take on different roles in a village. But how does that lead to resolving conflicts? Ashley Davis met researchers Prof. Rilla Khaled and Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis to find out more

Do you chuckle at the thought of a serious game? The phrase is an oxymoron. How can a game be serious? Games are meant to be fun, frivolous, a way to pass the time. Or else you sometimes hear that games are anything but frivolous. That video game violence in particular is a threat to social order. The idea that games can be used to advance human understanding about the world, and that they can help us to teach, train, or motivate people in some way, is something that still needs to enter our mentality.

Designing games to explore research questions and to solve real world problems is actually a very important aspect of games research, an area of applied research that now has a strong presence at the University of Malta with the establishment of the Institute of Digital Games. Researchers from the Institute work on European-funded projects to create games that tackle serious problems affecting children and adults alike.

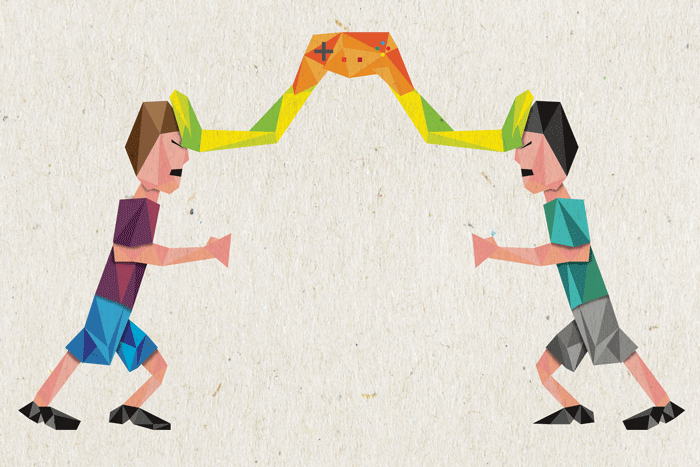

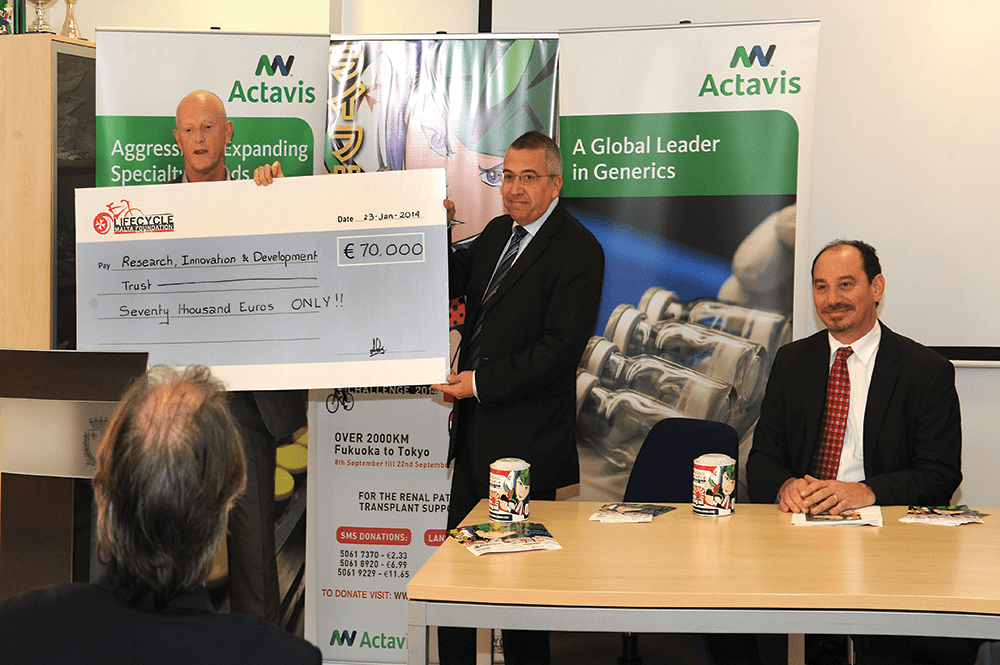

Village Voices has been voted the best learning game in Europe at the 2013 Serious Game Awards

Prof. Rilla Khaled and Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis are two researchers now based at the Institute of Digital Games who work on serious game projects. Khaled’s work focuses on serious game design, while Yannakakis is a specialist in artificial intelligence and computational creativity. Computational creativity tries to build upon the latest technological innovations in human–computer interaction that enable computers to act intelligently to some aspects of human beings. These two areas, game design and game technology, represent a large part of the teaching and research strengths of the Institute.

One game that Khaled and Yannakakis recently helped develop is Village Voices which has been voted the best learning game in Europe at the 2013 Serious Game Awards. It was developed as part of the SIREN project, an FP7-funded interdisciplinary consortium made up of researchers from Malta, Greece, Denmark, Portugal, the UK and the US, along with Serious Games Interactive, a Danish Games Studio.

Let’s take a look at what makes a serious game and think about what made the project a success and what didn’t work so well.

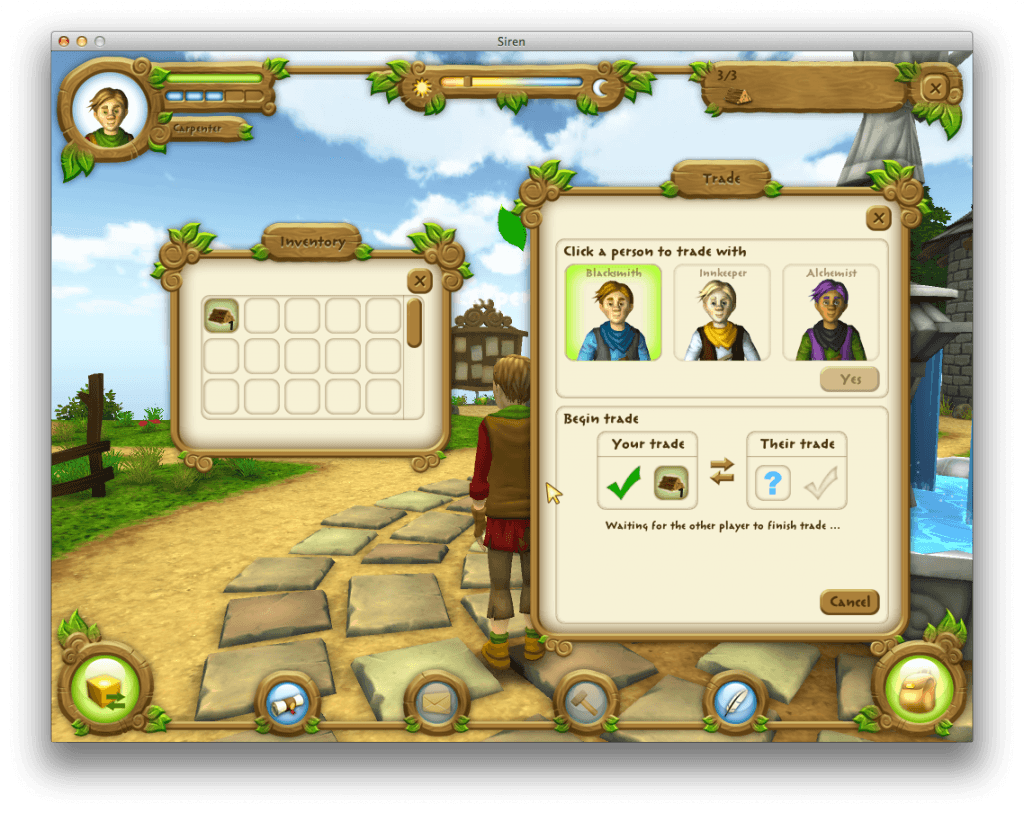

The serious side of Village Voices aims to help school children learn conflict resolution skills. Players take on the role of one of four interdependent villages that are situated in a farm setting and given various quests to complete. Sitting side-by-side at separate computers, they may collaborate, share resources and help each other, or they may spread rumours and steal from each other. Much like any playground setting, children can play nicely, or they can be bullies.

The purpose of the SIREN project was to apply the latest advancements in game technology to the creation of serious games. The brief focused on innovations in procedural content generation, an area of artificial intelligence that automatically builds game elements like game levels or quest structures that would otherwise need to be designed manually. Another part of this innovative technology is detecting the emotions of players. Physiological responses can be measure through various tech like Electroencephalographic (EEG) sensors that can be used to detect a person’s emotional state directly by reading their brain’s electrical signals. Virtual agents were another technology that interested the research team. These agents are believable non-player characters that interact with the player with perceived intelligence.

The idea was to then create a game that would adapt to player behaviour, using emotion recognition tools to create an individual experience for each player. The decision to focus the game on teaching children about conflict resolution came later. Rather than to create a game about bullying behaviour, which is what a lot of people think of when they picture conflict between children, the research team wanted to explore the kinds of everyday conflicts that take place in school-yards. Friendship disputes, differences in opinion, and arguments over the possession of classroom items might seem trivial to adults, but they are important problems for children for whom school is their entire world. The SIREN consortium envisioned a game where players could experience and resolve conflicts in a dynamic setting.

Some people who make serious games say that the serious application of the game should take precedence over fun. They say that serious games should offer players a safe environment to try out new behaviours. Khaled disagreed with this approach to game design. ‘Serious game experiences need to feel real and not trivial. Otherwise why would we then use them to raise a mirror to reality?’

Village Voices allows actions that teachers might find surprising. Players can be destructive in that world. They can steal from each other. The game gives aggressive players a noose with which to hang themselves. Knowing that the person whose labours you just destroyed, or who stole the items you were collecting, is sitting right there next to you intensifies the game’s emotional experience. Exchanges can become heated between players. It is these kinds of heated exchanges that often makes games fun.

Games are usually poor at provoking emotional responses. Village Voices does exactly that. Khaled told me about one session in a British classroom (the game was tested across Europe). A female student had such an upsetting experience that she cried. After reflecting on the incident with her teacher, the researcher, and the other players, the girl later returned to play again. Khaled thought this was a breakthrough learning moment for the student.

So Village Voices is a good learning tool, and it is also fun to play. But how successful was the team in applying game technologies like procedural content generation and emotion detection to its design? Khaled said that the experience of designing a game primarily for the purpose of testing technological innovations was the hardest part of the project. You might think that the role of a game designer is to work out the best solution to a problem given the technologies at hand. However, when the application of technology is the problem, the relationship between design and technology is more complex. Khaled said that the need to include particular game technologies in the design of Village Voices created a situation much like a rock band that needs to accommodate a peripheral member, such as a violin player. ‘While the violin player is not core to the project, the whole project needs to be compromised in some way in order to show off the violin player’s skills. It is not clear that the violinist is going to help the band make a new hit song, but it is clear he has to be there. So the band tries to find the violin player’s most positive qualities because he has got to be there.’

In Village Voices, the violin player’s best qualities are adaptive technologies that make the player experience more personalised. Because support for emotion detection plug-ins was never actually included in the final prototype, the game instead asks players directly how they feel about events in the game and introduces variations to the player experience according to their responses.

So far we have seen that Village Voices was successful according to the popular opinion of game-design peers at the European Serious Games — it won an award. We have also seen anecdotally that it is a provocative, if not fun game, based on the British student’s emotional response. But what does the SIREN team think about the game?

You cannot sit a child down in front of a computer and hope that they will magically learn something

According to Khaled, it can be difficult to implement learning games in classroom settings, and even more difficult to properly evaluate them. Project funding usually runs dry after around three years, and games take most of that time to develop. Gaining access to schools is also difficult. The game is a good fit for classes like social studies that are often held only once or twice a week. Together with the problem of semester breaks and short evaluation periods, as well as the tendency for teachers to have access to only a few computers often equipped with obsolete hardware, researchers would rarely see students engage with Village Voices over a long period of time. All these things place limitations on the design, testing, and evaluation of games for research purposes.

Rigorous evaluation is important as, ultimately, learning games are not black box tools. You cannot sit a child down in front of a computer and hope that they will magically learn something. That vital learning moment comes when players discuss their in-game experiences. As Khaled explained, ‘Playing the game is just half the experience. The other half is the subsequent discussion of the game experience.’

Given that discussion is so essential to the evaluation process, and that it is so difficult to get a sample of those discussions in a research setting, I asked Khaled if it was possible to turn the discussion into a game as well, to include it as part of the package. Khaled mentioned the meta-game, the part of the game where a player is both playing and watching themselves play the game. It is in the meta-game that players achieve the highest level of reflection. It works well as a kind of after-game discussion, a debriefing for players as they leave behind the conflicts of the game world and return to the everyday life of the school-yard; but Khaled added that of course it could be turned into a game. Achieving this level of reflection in the game package itself is just another challenge for the designers of serious games.

The Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta offers word-class postgraduate education and research in game studies, design, and technology. The inter-disciplinary team includes researchers from literature and media studies, design, computer science and human-computer interaction. Visit game.edu.mt or contact Ashley Davis (ashley.davis@um.edu.mt) for information about the Institute’s Master of Science (taught or by research) and Ph.D. programmes. This article forms part of The Gaming Issue.

Find out more:

-

Cheong, Y-G., Khaled, R., Yannakakis, G., Campos, J., Paiva, A., Martinho, C., Ingram, G. A Computational Approach Towards Conflict Resolution for Serious Games (full paper). In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games, 2011.

-

Khaled, R. and Ingram, G. Tales from the Front Lines of a Large-Scale Serious Game Project (full paper). In the Proceedings of CHI ’12, 2012.

-

Vasalou, A. and Khaled, R. Designing from the Sidelines: Design in a Technology-Centered Serious Game Project. In the Proceedings of the CHI Workshop Let’s talk about Failures: Why was the Game for Children not a Success? CHI ’13, 2013.

Some SIREN Gameplay Shots

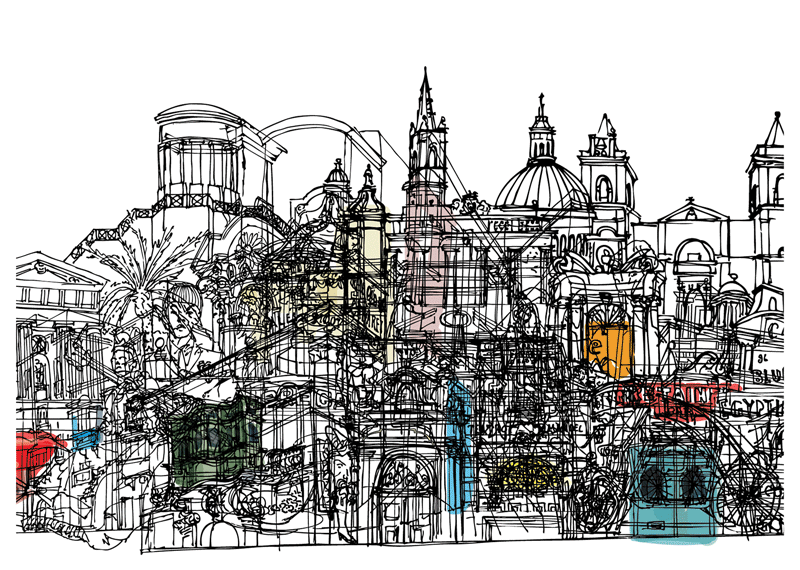

Multicultural Valletta

Valletta will be the European Capital of Culture in 2018 and has served as the centre of multiculturalism in Malta since its beginning. Built soon after the victory of the Hospitaller Order of St John over the Ottoman Empire in 1565, it meant to serve as their Fortress Convent. The knights came from all over Europe and helped attract people from all lifestyles. Valletta had a cosmopolitan atmosphere that impressed itself on the character of the city helping to enrich the country especially in creativity. The Order of St John managed to establish a ruling system which seeped down the social scale and gave character to the Harbour area. The cultural magnetism of the City was underlined by its political centrality. Functioning as an administrative capital, Valletta determined the fashions and values of the Grand Master’s court. Similar to early modern European capitals, Valletta was a powerhouse of cultural change.

British rule in the 19th century introduced new cultural elements with an Anglo-Saxon tone. The Royal Navy and the numerous other ships that anchored in Valletta’s adjacent harbours poured in many foreigners who came for short or long stays and mingled with the locals. This made Valletta a melting pot of nations, cultures, tastes, values and mentalities. Yet novelties did not manage to destroy or replace what had already been entrenched in the life and fabric of the city. All it did was enrich it further. The city put on a new dress but did not renounce its soul, and the residents adapted to the new trends without forgetting their roots.

Valletta continued to grow in its multicultural mentality, a natural process for a central Mediterranean city. It is an administrative and cultural centre. Over five centuries, people from different cultural environments have thrived and lived harmoniously together.

This article is an edited version of the paper delivered at the VIIth Interdisciplinary Conference of the University Network of the European Capitals of Culture (UNeECC) in Marseille in October 2013 by Prof. Carmel Cassar (Rector’s delegate) and Dr George Cassar, members of the Valletta 2018 Foundation Research Coordinating Committee.

Innovation in Business

Being in the second year of my banking, finance and management studies, innovation in these sectors is a key part of my curriculum. In banking one can easily see developments with the introduction of banking by telephone, internet and mobile. Similarly with management, recent growth has allowed the sector to grow and develop expertise in management of projects, accounting and supply chains.

Being in the second year of my banking, finance and management studies, innovation in these sectors is a key part of my curriculum. In banking one can easily see developments with the introduction of banking by telephone, internet and mobile. Similarly with management, recent growth has allowed the sector to grow and develop expertise in management of projects, accounting and supply chains.

Innovation has exponential potential to foster new solutions, initiatives and jobs. Younger graduates need to create new opportunities. For Malta to improve its competitiveness and attract investment we must turn challenges into opportunities. During Ireland’s EU Presidency, in the first half of 2013, the negotiations led by Dublin saw Malta secure €1.128 billion for the 2014-2020 Multi-Annual Financial Framework. The possibilities for Malta are endless. On top of this framework lies the Horizon 2020 Programme, where countries can compete for over €80 billion set aside for innovation. These funds should be used strategically in Malta to improve existing sectors and to find a way to create new markets and jobs. This growth would build Malta’s competitiveness.

“For Malta to improve its competitiveness and attract investment we must turn challenges into opportunities”

SMEs (small and medium sized enterprises) are being greatly encouraged by the EU since they are seen as a route out of the recent economic crisis. The Horizon 2020 programme gives priority to SMEs.

Malta can win more of these funds by looking at what Horizon 2020 aims to achieve, that is leadership in a world of competitive science and to realise innovations leading to societal change. These could be in the areas of biotechnology, clinical research and green technologies. We need systems that change the way we live and think.

In the global economy, it can be hard to be innovative and entrepreneurial as we have grown accustomed to depending on other countries to do our work. Instead of waiting for new technologies and developments to emerge so that we can replicate them, we should encourage the young generation to open new doors that could lead them to success. Thus, inspiring people to think outside the box and to be creative starts from an early age. This train of thought must be cultivated at the heart of the education system where students start to think about jobs and the future.

Last December, I had the opportunity to see this when I visited Facebook’s Headquarters in Dublin as part of the ASCS study trip. There is considerable scope for further research into virtual platforms linking social media with innovation in business.

Albert Einstein once said ‘Most people see what is, and never see what can be,’ which is exactly why we need to shift the focus on what can be done, rather than what has already been done.

Getting the Rhythm

Music has changed society. Stephanie Mifsud met ethnomusicologist Dr Philip Ciantar to talk about music from all over the world. Studying diverse musical traditions has taught him about himself and how music can bridge cultural divides to bring us together

Classical, romantic, baroque, rock, hip hop… music continues to change throughout the years, yet we all look for that beat that gets us moving. How can we not when music is such an important part of our life?

Music is found everywhere: on television adverts, films, on the radio and at places of worship. Our society immerses us in it for hours every day. A person will listen to music that represents the way they feel. Music has the potential to influence moods, feelings, and thoughts.

“Music opens infinite thinking modes unknown to us and uncovers situations we wouldn’t otherwise experience”

Legendary rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix, told Life magazine in 1969, ‘I can explain everything better through music. You hypnotise people to where they go right back to their natural state, and when you get people at their weakest point, you can preach into their subconscious what we want to say.’

Music, like language, has a common factor: a person’s active role. People create music. No music can exist without the people who make it.

The Ethnomusicologist Dr Philip Ciantar (University of Malta) is interested in both the music itself, as a humanly organised sound, and the musicians. His research focuses on understanding how people worldwide think about music and how that affects their music. He meets and interviews countless musicians and their audiences. People’s thinking about music is shaped by who they are, their world-view, and how they use their creative imagination to create music. Take John Lennon’s song Imagine. The song has touched countless around the world. It might have changed the way people see themselves, relate to the people around them, and influenced future songs.

Music to say ‘Hello!’

Ciantar explains that ‘by listening to and exploring music from different countries we can understand other cultural and social realities. Music opens infinite thinking modes unknown to us and uncovers situations we wouldn’t otherwise experience.’ According to him, ‘music can highlight social issues or it can make a connection with different cultures when many other avenues fail’. This is the acceptance of ‘otherness’, the concept of what makes us different from each other culturally and socially. Music can be a very effective medium.

Acceptance of different cultures needs to be taught from a young age. Music can help in showing people the advantages of multiculturalism. Ciantar suggests that, at school, children can be taught instruments used in different cultures. This would help students understand and appreciate not just the instruments but also the musicians playing them. He continues, ‘you need to be open to other opinions, cultures, and traditions’ and music provides the right scenario.

Understanding music globally should lead to appreciation of diverse sounds and how they are made, communicated, and transformed into meaning. The musical process reveals humanity and here otherness surfaces as a challenge for us to deal with. It is up to us to then connect with different cultures we might consider alien.

People come together through music. The village feast is Malta’s best example of unity through music. During a feast a quiet pjazza transforms into a music concert, a fireworks festival, and a food extravaganza — uniting the whole community. These celebrations bring people together ignoring their differences.

Multiculturalism is a worldwide phenomenon. Malta is becoming multicultural and, as Ciantar comments, ‘music is an indicator of what is going on. Performances of African music at the Marsa Open Centre can be interpreted as a plea for social acceptance and cultural integration. Slavic street players in Republic Street play Bach’s violin partitas to make us connect with them culturally. Once we are connected they play a nostalgic lullaby from their homeland to make us feel the pain of distance and sympathise with them. Undoubtedly, music serves as a social text; in itself, an intriguing sonic document that links the evident with the untold or even ignored.’ This is the power of music and the concept of otherness that can shape our thoughts on multiculturalism and readiness to accept others’ views.

“Undoubtedly, music serves as a social text; in itself, an intriguing sonic document that links the evident with the untold or even ignored”

He became even more aware of multiculturalism while conducting his Ph.D. research. He went to Libya to experience different cultural backgrounds and traditions. He worked with Libyan musicians, attending their rehearsals, talked to people on Tripoli’s streets about the musical tradition of ma’lūf (a tradition valued for its Andalusian legacy), and sneaked in percussion performances with Libyan musicians. Apart from writing a book, these experiences helped Ciantar understand otherness and the challenges it implies.

Ciantar’s first experience with ethnomusicology and otherness goes back to 1991, when he was inspired by the writings of John Blacking and Bruno Nettl, and started researching Maltese folk music għana. He saw how the għanejja performed in two different contexts and their music changed accordingly. The music they sang was more elaborate in their regular bars when compared to stage music with an unknown audience.

Otherness can also be scrutinised through musical translation. Ciantar researches musical translation: how we digest and eventually accept music that might not be initially appealing to us. Recently, he composed a Maltese festa band march out of tunes that he had recorded in Libya. The process allowed him to investigate the music and himself. He had to take elements of one musical tradition and apply it to another that was culturally remote, using himself to understand the process of how a person thinks and transforms thought into music.

Ciantar is very hopeful of the musical evolution in Malta as this is being influenced by the different cultures that people encounter everyday. This will create a more varied musical scene. Ciantar can already feel the difference.

Stephanie Mifsud is part of the Department of English Master of Arts programme.

[ct_divider]

Find out more:

-

‘The Process of Musical Translation: Composing a Maltese Festa Band March from Libyan Ma’lūf Music’, Ethnomusicology, 57(1): 1-33 (2013).

-

The Ma’lūf in Contemporary Libya: An Arab Andalusian Musical Tradition. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. (2012).

-

‘From the Bar to the Stage: Socio-cultural Processes in the Maltese Spirtu Pront.’ Music and Anthropology in the Mediterranean Online (2000)

John Lennon’s Imagine

Andalusian Music

Għana Maltija—Traditional Maltese music

Forgetting what you can’t remember

How does the loss of memory change a person? Can media replace memory? Giulia Bugeja asks several researchers to find out the affect on cultural memory and she also touches on dementia

When Mike* went to the nursing home that evening to visit his grandmother Maria*, she was worried that he wouldn’t be able to find her because the caretakers had changed her room. Mike tried explaining to her that her room on the 4th floor had been refurbished a year ago, but she couldn’t remember.

‘Can life without memory be considered a meaningful existence?’ asks Dr Charles Scerri (Malta Dementia Society, and Department of Pathology, University of Malta). Dr Scerri researches dementia. He is currently examining which physical environments and what sort of psychosocial wellbeing can improve life in local dementia hospital wards. In fact, Dr Scerri reports that today there are over 44 million people suffering from some form of dementia. That is around 100 times the Maltese population. He asks, ‘what type of society can we end up with if we are wholly made up of individuals with no past and an uncertain future?’

With more people relying on new media technology to record information and experiences, Dr Scerri’s question faces a future society where media could replace memory. ‘It would be short-sighted to think that new media will have no long-term influence on the complex nexus of personal and cultural memory’, says Dr James Corby (Department of English, UoM).

Photography already acts as a surrogate for memory. But, it does not stop there; theorist Roland Barthes goes one step further saying how photography can capture details missed by the human eye. As developers of new media strive to enhance experiences, more users are adopting them. In the final quarter of 2012 alone, Apple sold 37.4 million iPhones. This smartphone, equipped with HD video, an in-built camera, calendar, and interactive 3D map helps people capture memories and avoid having to remember appointments or directions. It even comes with Siri, your own ‘personal assistant’, to use Apple’s words.

Despite these abilities, Dr Corby is sceptical. As a researcher working on the interfaces between literature, philosophy and culture, Dr Corby thinks that the rich tradition of the humanities should inform debates about cultural memory. ‘The idea that a facility to record memories leads to the diminishment of personal memory is by no means a new idea. Indeed, it is precisely the accusation that, in Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates makes against writing.’ Writing did not steal our ability to remember and neither should new technologies.

“You can never really know if what she’s saying is true because her memories are not always real”

So what would happen if old or new media failed us? When the accounts office of the family business burned down, Mike could relate to his grandmother’s anxiety due to her lack of personal memory. All the accounting records, invoices, transaction records, and overseas payments were destroyed. The accountant was so shocked that he still will not enter his old office after 15 years.

The accountant had to keep paper records. There was too much information to remember and they couldn’t memorise it all. Although they recorded the information they still lost it in the fire.

| More about Alzheimer’s in Malta |

Dr Scerri has collaborated with the Department of Pathology to launch the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Group (University of Malta). Their objective is to gather several multidisciplinary professionals to ‘promote and facilitate research and scientific collaboration in Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia’. Together with Trevor Zahra, he recently released the publication X’ħin hu? Fatti dwar id-dimensja (What time is it? Facts about dementia). Dr Scerri has collaborated with the Department of Pathology to launch the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Group (University of Malta). Their objective is to gather several multidisciplinary professionals to ‘promote and facilitate research and scientific collaboration in Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia’. Together with Trevor Zahra, he recently released the publication X’ħin hu? Fatti dwar id-dimensja (What time is it? Facts about dementia). |

We all risk losing both valuable information and the recollection of experiences. So what would happen if Malta became a nation of people without a memory of important events? For Dr Corby, a society which relies on new media and less on memory ‘might then lead to a complete eliding of any difference between personal memory and an increasingly undifferentiated surfeit of readily available cultural memory — a sort of technologised and globalised cultural eidetic memory’.

There’s also the possibility that media such as photographs could lead to the creation of cultural memories which never took place. ‘I imagine false memory to be the norm—it would be naïve to think that the visual representation of a culture […] is free from ideology’ says Dr Corby. Our national identity will instead be formed around uncertain events.

Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of American soldiers raising the American flag on Mount Suribachi on the island of Iwo Jima signifies a moment of national pride for Americans. Few Americans are aware that the photograph shows the flag being raised for a second time. The first flag was too small but the second larger flag would be seen by incoming ships.

Similarly, on the 4th floor of a nursing home, an old woman recalls how the nurses refused to take down the Christmas decorations. In her room, there was only a lone poppy. ‘She often creates stories in her head’, says Mike. ‘You can never really know if what she’s saying is true because her memories are not always real.’

‘Memories are created by altering a set of connections between brain cells so that one cell stimulates the others,’ says Jonah Lehrer, Wired Magazine. By creating memories, we are literally rewiring our brains. Every time a memory is recalled, the connection between brain cells is restructured and the memory altered depending on the stimuli of the current situation. This means that whilst media may fail us, so might our memories.

Will a nation inevitably make the same mistakes because its people cannot remember past experiences or because they replace them with false ones? When asked how memory recall can be assisted, Dr Scerri acknowledges that media is a useful tool in improving memory, as ‘memory albums are extremely valuable for individuals with dementia in facilitating memory events and in reducing anxiety and confusion’. Perhaps these tools can help Mike’s grandmother.

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of the people mentioned in the article.

Giulia Bugeja is part of the Department of English Master of Arts programme.

Look out for an in-depth feature on dementia in the next issue.

A Good Cause for Research

Why should public, private, and non-profit entities invest in research? Several reasons exist.

Firstly, research is key for our future. Research helps drive new knowledge that will improve the world. Society depends on research, across a wide range of disciplines, to strengthen our quality of life and sustain economic stability. By raising funds for University research the RIDT is surely not trying to reinvent the wheel. On the contrary, throughout Europe, the US and Asia public universities are enhancing their Government funding through various initiatives to sustain important research. Universities all across the globe appeal to public entities, private individuals and NGOs to fund research and invest in our society’s future.

Locally, we have just started scraping the surface of fundraising for research. Recently, the RIDT received a number of important donations which shall serve to continue fostering local research. In the first of its kind, we received €55,000 from local NGO ‘Action for Breast Cancer Foundation’ (ABCF), raised through the ALIVE Cycling Challenge. They are being used to launch a Ph.D. studentship in breast cancer research. The Lifecycle Foundation has also donated €70,000 towards kidney disease research. These NGOs have followed a stream of public and private entities, as well as students, who have been donating money for research for the last three years.

Secondly, don’t you want to be part of something bigger? You probably cannot find the cure for cancer yourself, but everyone can contribute to make that a possibility. As the University’s Research Trust, we do not only want to attract big corporate companies or NGOs to donate money, but we also want you — the students, the alumni, the professionals, the workers, the parents, to realise that donating for research is a noble cause. A recent Christmas campaign at the University of Malta that was spearheaded by KSU, the UoM staff and the Chaplaincy managed to raise €12,000 from students, staff, and academics on campus. A third of these funds were donated to the RIDT, which were devolved to the Department of Anatomy. They will be invested in specialised research projects focusing on specific strands of cancer, such as leukaemias, sarcomas, brain tumours, breast and colon cancer.

Research affects our day-to-day lives. Though research discoveries take time and need constant investment to benefit our society, we can come together as a Maltese community by investing in research for good causes. Ultimately, let us imagine a world where we have cured all major diseases, where we can move objects with our thoughts, and unravel the mysteries of the universe.Imagine, and let’s make it happen!

RIDT is the University’s Research Trust aimed towards fostering awareness and fundraising for high-calibre local research. We aim to achieve this by raising funds for various research projects undertaken at the University of Malta. Please visit www.ridt.eu to donate and our Facebook page on www.facebook.com/RIDTMalta for more information about our latest events and initiatives.

Cybersexuality

Relationships have changed hand in hand with society. More couples are living far apart from each other. Marc Buhagiar speaks to Mary Ann Borg Cunen to explore how technology can lend a hand. Illustrations by Sonya Hallett.

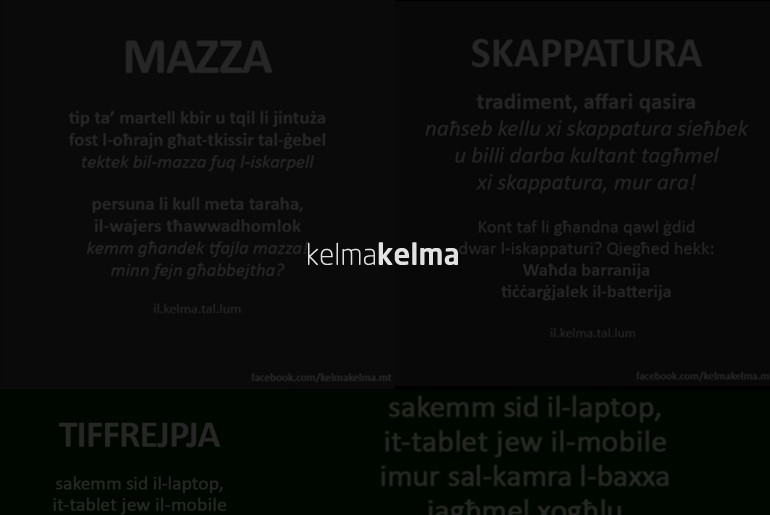

Kelma Kelma

With a massive following of 25,000 people, Kelma Kelma is the Facebook page that has taken Malta by storm. From a simple collection of linguistic curiosities borne from one man’s love of the Maltese language, it has developed to become an unconventional but highly effective teaching tool. This is the journey of Kelma Kelma from the man behind the computer screen, Dr Michael Spagnol.

A think-tank for Humor