Artificial Intelligence (AI) is revolutionising the world. We have self-driving cars, algorithms determining future market patterns, and computers diagnosing disease. We believe that AI is supporting huge developments in healthcare.

Continue readingThe Comfort Trap

A good way of understanding a concept is by looking at the way people use it in everyday conversations. Language embodies the accumulated wisdom of countless speakers who have expressed their understanding to others over long periods of time. By analysing the way we use the term ‘comfort zone’ we can better understand what we actually mean when we use it.

Continue readingWipe your shoes and clean your mask

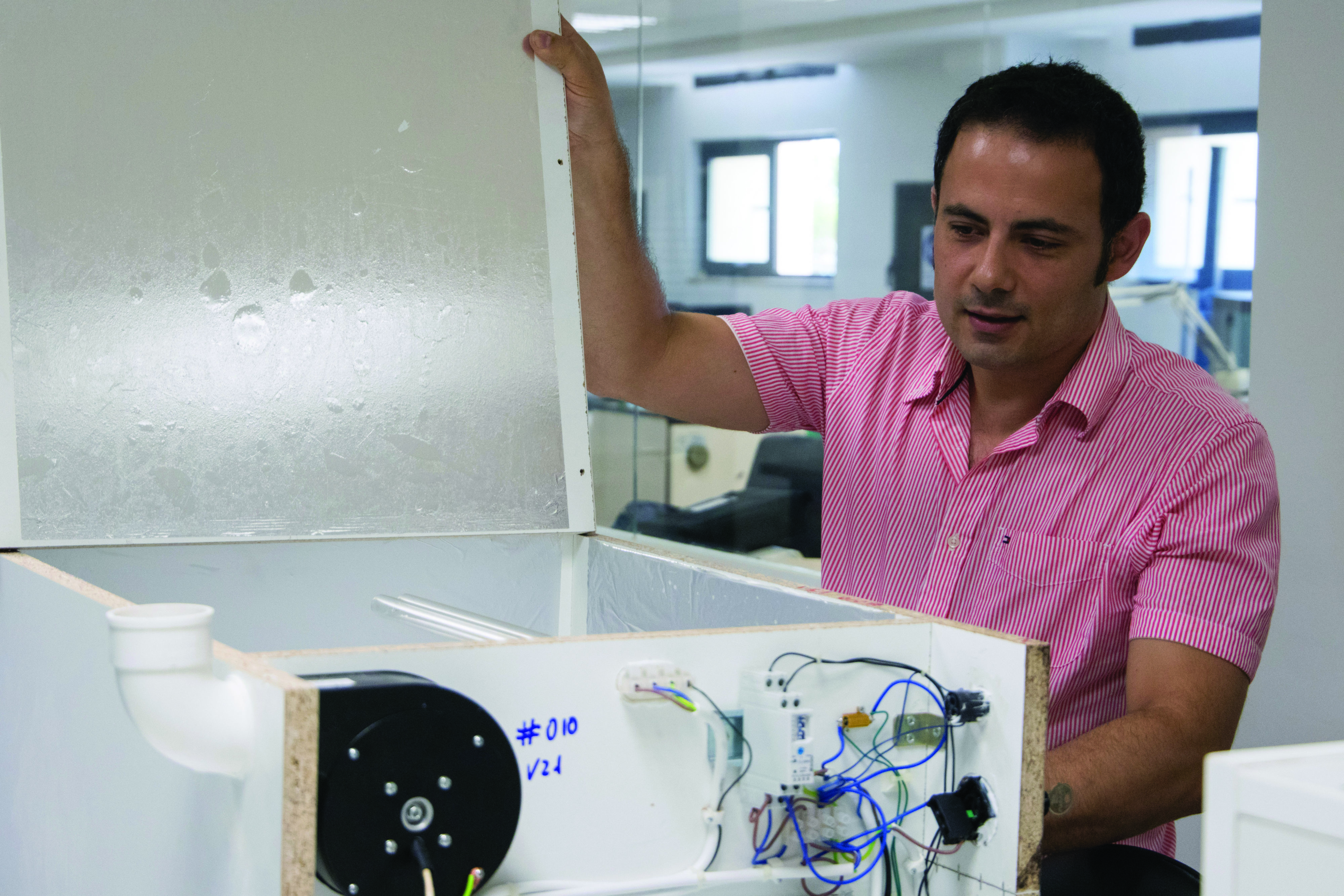

Face masks are the new essential accessory. Have you ever cleaned your mask and wondered if you’re doing it properly? What can front line workers do if they run out of clean masks at hospitals? Can they disinfect their single-use speciality masks, called respirators? Can they wash them like we do our cloth face coverings? Dr Ing. Marc Anthony Azzopardi, from the Electronic Systems Engineering Department, talks to THINK about how our doctors and nurses are extending their stock of speciality face masks by cleaning them in an equally special way.

While many were hoarding toilet paper for the impending apocalypse, others were planning ahead, scavenging for parts to create a machine that could sanitise face masks. The idea is to protect citizens and front line workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr Ing. Marc Anthony Azzopardi told THINK about his new invention. He has developed an electronic method of disinfecting face masks. The idea started germinating in Azzopardi’s mind in January, when some of the earliest cases began. Back then, masks started selling at €10 each. By April the price had skyrocketed to €300 — that is, if you could even find one. In Malta they were sold out!

Azzopardi spoke about N95 and N100 respirator masks, which filter at least 95% and at least 99.97% of airborne particles respectively. They aren’t usually worn by medical professionals, except when treating dangerous respiratory diseases like tuberculosis. Instead they are more routinely used by scientists and engineers when handling toxic materials and fine dusts.

These masks sit tighter against a wearer’s face, forming a seal. They are made up of several layers: an external hydrophobic layer that repels water, a stiffener layer, an electrically charged, non-woven melt-blown fabric, and finally a comfort layer on the inside. The electrical charge is applied during manufacturing. Once this charge is dissipated (through washing) the masks stop working properly.

Coronavirus is killed when washed in 70% alcohol or with bleach containing 5.25%–8.25% sodium hypochlorite. The problem is that, unlike regular cloth masks, these respirator masks cannot be washed in liquids, as they then lose their electrical charge and become much less effective at filtering particles. So how can you disinfect them after use?

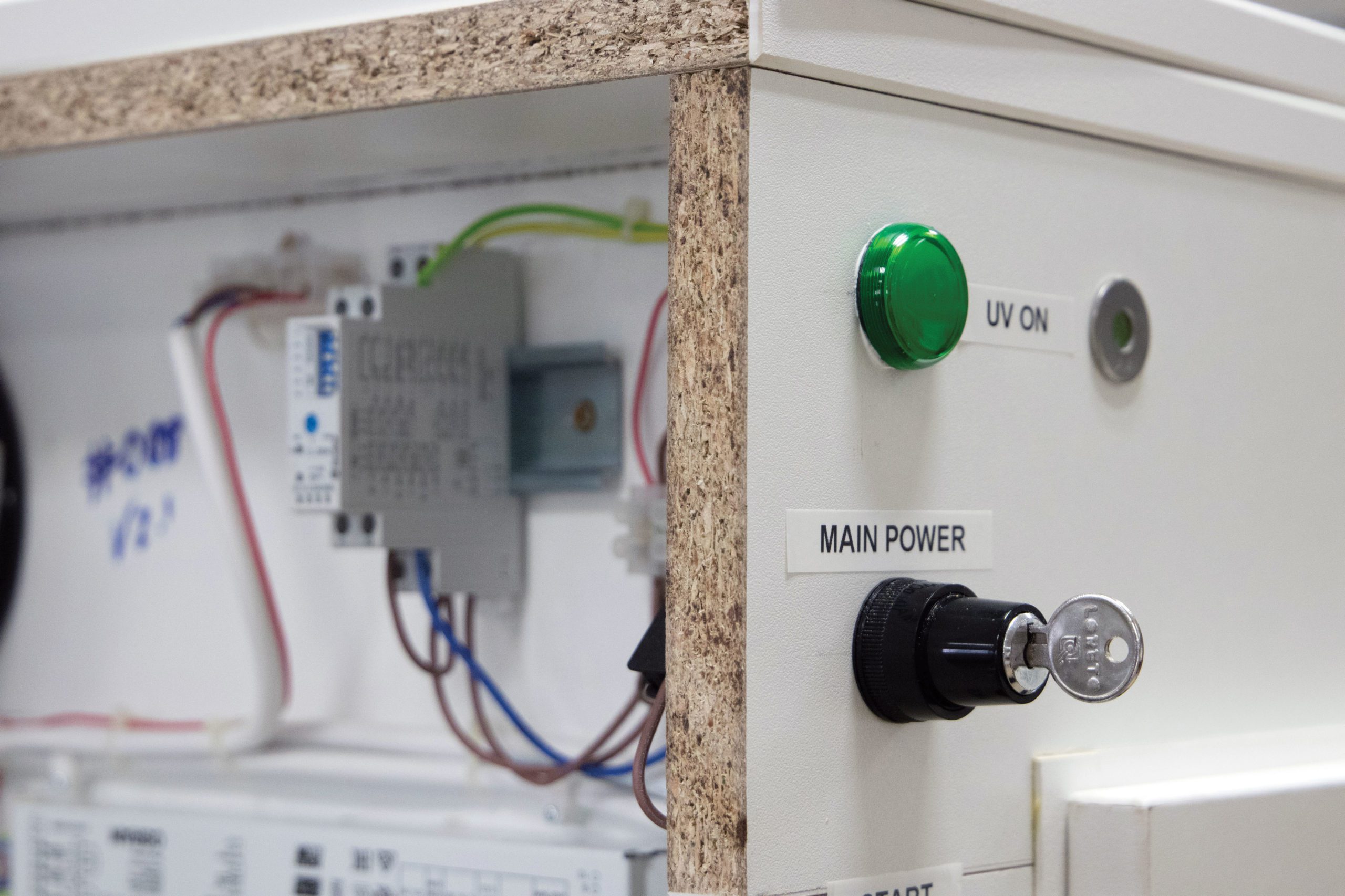

Azzopardi realised that by using UV light, it was possible to disinfect the mask without affecting its electrical charge. His solution was elegant and simple: a sealed box which would store the mask and expose it to UV light from all directions — effectively creating a sanitisation chamber.

Essentially, the sanitisation chamber is an enclosure which uses a low-pressure mercury lamp to generate UV inside. Following a discussion with the Infectious Disease Unit at Mater Dei, the design evolved and was adjusted to suit the masks being used by the hospital staff.

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, similar methods were being trialed in the US, the difference being that instead of using a box, US scientists were using a room to leave the masks hanging. The room would then be exposed to UVC through a small tower, disinfecting the face masks. Contaminated masks would be brought to this room from all over the hospital for cleaning, the hazards created by the complicated logistics notwithstanding.

Disinfection was made possible by using UV light, of which there are 3 types: UVA, UVB, and UVC. Very few organisms have evolved to resist UVC, and upon exposure, DNA gets tangled up, making it impossible for the virus to replicate in our cells. COVID-19 uses ribonucleic acid (RNA), which is also susceptible to UVC. Using UVC light at around a 260 nanometer wavelength can “inactivate” the RNA code for COVID. This makes it harmless if breathed in.

The system itself is foolproof. It prevents the user from getting exposed to dangerous UVC radiation. A timer makes sure that users leave the masks for the right amount of time. And, it tests that all of its systems are functioning before starting. When the team started building this system, they didn’t have access to UV measuring instrumentation. This meant they worked solely off calculations to get it right. However, after weeks of work, the team managed to perfect their design.

Nonetheless, face masks do not last forever. Even UV exposure can wear them down eventually, but only in large doses. You would have to get rid of your respirator masks long before the UV damage became significant, because of dirt or mechanical wear and tear breaking the mask down.

Azzopardi and his team’s efforts have helped to safeguard numerous front line workers from running short on clean supplies, and their system has earned them an award for the top solutions in response to the MDIA / Covid initiative. It is thanks to the scientific community and their efforts that we can have the technology for a safer future. However, creating that ideal future is up to all of us. Stay Safe!

Further reading

Covid-19 – Malta Digital Innovation Authority. Mdia.gov.mt. (2020). Retrieved 23 October 2020, from https://mdia.gov.mt/covid19/.

Keepers of the Past and Pioneers of the Future

Museums are a portal into the past. To create a sustainable future demands understanding and learning from this past. From Art Strikes to Biomimicry, Sandro Debono explains how many modern museums are taking a more active role in shaping the way our future unfolds.

My museum and curatorial practice have always been informed by theory and hands-on practice. Thinking through problems to find appropriate solutions informs my practice throughout, and recent circumstances have made me aware that this has become a highly sought-after skill. The COVID-19 pandemic can be seen as a negative disruptor. I prefer, instead, to consider the silver lining whereby the pandemic becomes an accelerator for change. The silver lining is for that potential for change to happen in significant and tangible ways — which is where museums come into the picture.

We rarely think about museums as public spaces where collections become resources that inform discussions and rethinks of long-established narratives and perspectives oftentimes considered by many as cast in stone. The museum is often understood as a tangible metaphor or a stereotypical idea rather than a response to the needs of a particular ecology to which it relates and responds to.

At the other end of the spectrum, climate action has been on the national agenda in fits and starts, with the country now unveiling an ambitious climate action plan to achieve net-zero emissions over three decades. Perhaps the most symbolic action is the unanimous declaration of a climate emergency by Malta’s national parliament in 2019. The reduction of greenhouse gases and extensive use of renewable energy resources has been on the national agenda for close to a decade or so. There is no question that Malta will be impacted in one way or another through rising sea levels and other effects. There is much that needs to be done, and the willingness to address this ever-pressing challenge requires increased awareness and outreach. Museums and climate action are far from being dissonant, disconnected voices. Indeed, one can become the voice of the other in meaningful ways.

Climate Action Advocacy

Museums have a voice. They also have things to say that are equally relevant to the present as much as they are to the past. One of these pressing matters, temporarily displaced to the shade of the COVID-19 pandemic, is climate change and the ever-more-pressing need for action. The obvious choice of institutions to take action would be science and natural history museums. Indeed, the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Natural History (part of the International Council of Museums), has been exploring ways and means to stimulate conversations about climate change. The international museum landscape has welcomed new museums dedicated to climate change in Hong Kong (Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change), Germany (Klimahaus 8°), China (Low-Carbon Science and Technology Museum) and Oslo (Klimahuset) since 2013. The entire international museum landscape has been active on this issue for quite some time. An ever-increasing number of museums have featured climate change in their public programming, and some are joining forces more than ever before. One example is the Coalition of Museums for Climate Justice, mobilising Canadian museum workers and their organisations to develop public awareness, mitigation, and resilience in the face of climate change.

Last year, the Museums for Future movement was launched. It is a global collection of museum workers, cultural heritage professionals, and many others in support of Greta Thunberg’s Fridays For Future Movement.

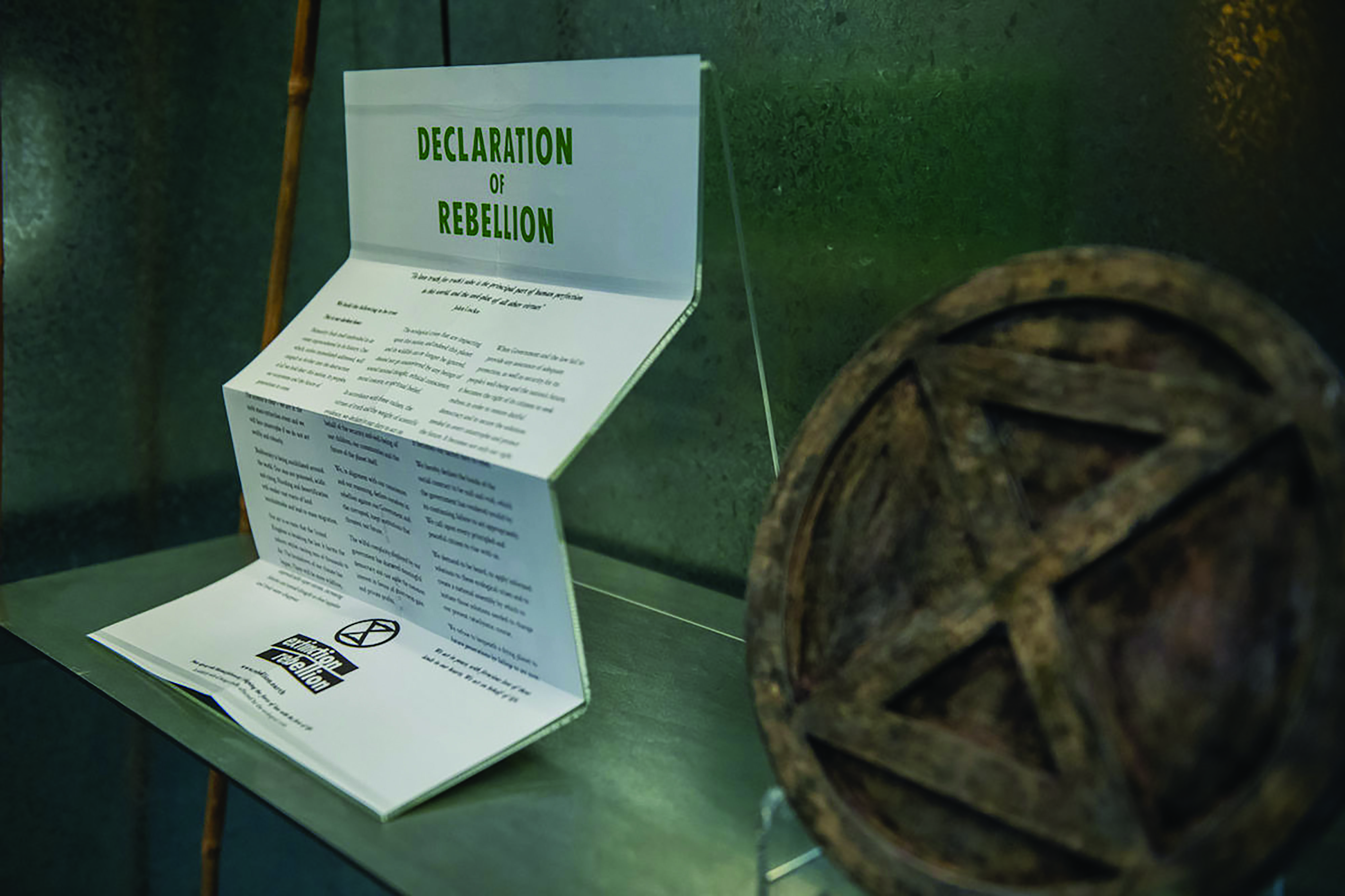

Museums can be both advocates and activists. One particular action hitting the headlines, also promoted by Museums for Future, is the art strike. This works by museums covering artworks on environmental subjects or themes for a day. The platform has a toolkit to guide and support institutions interested in calling art strikes. The Victoria and Albert Museum took things one step further. It partnered with Extinction Rebellion, the activist group calling for urgent climate action, to present exhibitions featuring material culture created for the purpose of protest. Since then, the museum has acquired artefacts produced for the purpose of protest, comparing the visual impact of the group’s campaigns to that of the suffragettes.

The Environment as Mentor

Protests have a flipside. Museums can become more aligned to natural processes. Museums can reduce their carbon footprint. Another step is to recycle and use eco-friendly materials in exhibition displays. Aligning museum institutions and their role in contemporary societies as public spaces is where biomimicry thinking comes into the picture.

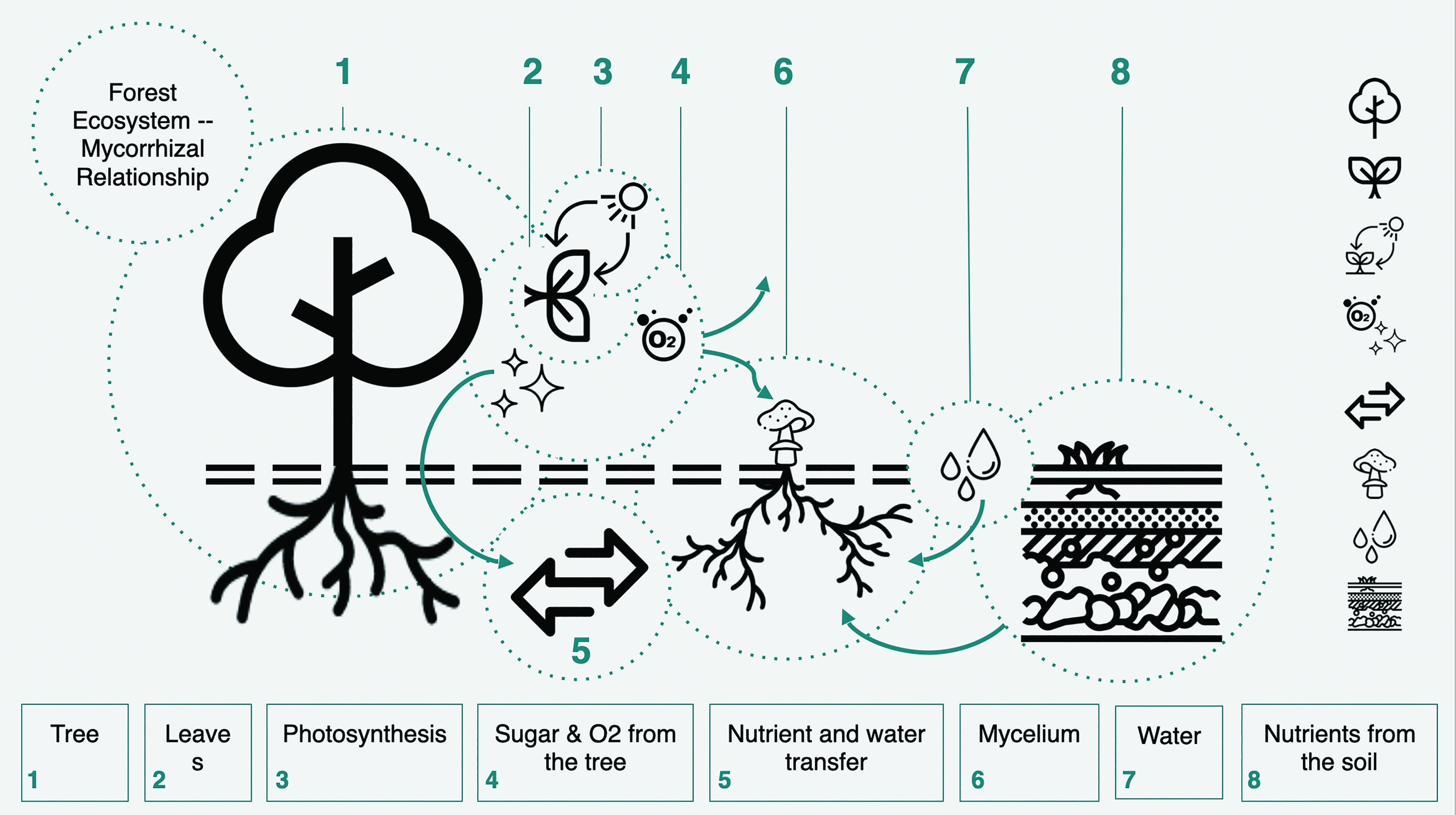

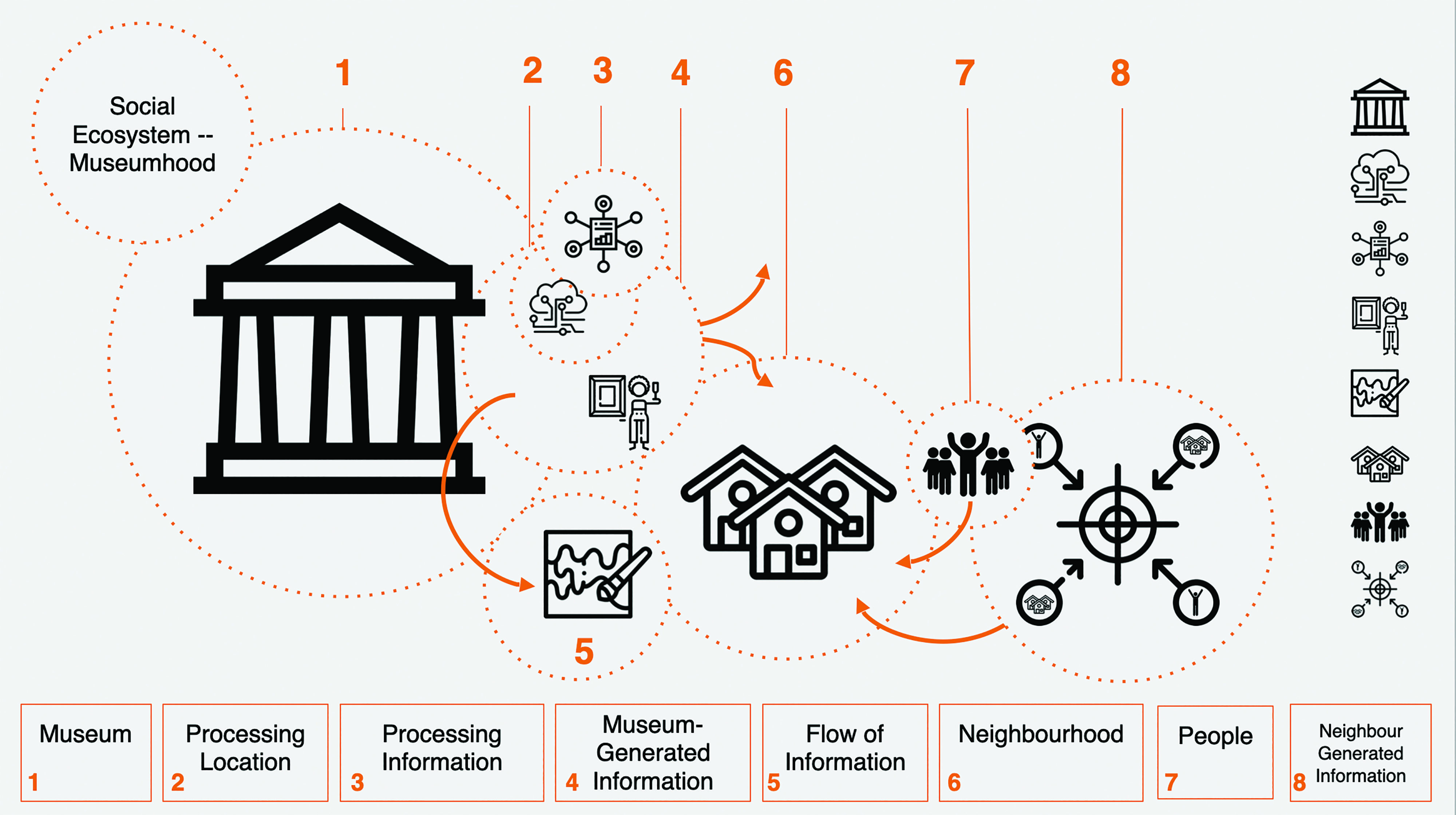

Biomimicry is an approach to innovation informed by adopting strategies found in nature for the purpose of developing sustainable solutions to human challenges. Janine Benyus’ book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature (1997) popularised this thinking. For biomimicry, innovation is informed by the natural world, leading to rethinking workings, management models, programming, and outreach. It is about the willingness to shift from ‘how might we’ to ‘how would nature’ do it in order to understand the underlying principles of nature for museums to create symbiotic relationships with their neighbours.

Biomimicry thinking can inspire museums to adapt, rethink, and reinvent themselves. Biomimicry can help museums understand the ecosystem they exist in and how it differs from nature. The institution would also need to translate science-driven and nature-informed biological data into design principles. Impact and sustainability would need to shift from the yardstick of efficiency and numbers, to the extent of systemic innovation introduced and the impactful change it has on the museum.

By looking closely at natural ecosystems, we can reinvigorate and reimagine the way museums operate, expanding their outreach and engagement in sustainable and innovative ways.

Further Reading

Museums & Climate Change Network. Museums & Climate Change Network. Retrieved 1 November 2020, from https://mccnetwork.org.

Museums For Future – Culture in Support of Climate Action. Museumsforfuture.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020, from https://museumsforfuture.org.

The Biomimicry Institute. Biomimicry.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020, from https://biomimicry.org.

Do you speak ‘Dance’?

From professional globe-trotting performer to populist teacher, Cassi Camilleri speaks to dancer and choreographer Karolina Mielczarek about her mission to bring dance to the masses as a form of self-expression and communication.

Continue readingMalta’s Paganism: A Dance Between Archaeology and Anthropology

The prehistoric Megalithic Temples found around Malta were once home to an ancient civilization. We have no records of how their spirituality was practised—only limited archaeological evidence. However, conducting an anthropological study of contemporary Neopagan communities may provide insight into the rituals of these mysterious people.

Continue readingI’m dreaming of a Green Christmas

Cultivating a healthy planet requires us to shift from a consumerist mindset towards sustainability. Eco-sustainable gifts are a great way to spread Christmas cheer while promoting sustainability.

Celebrating a ‘Green’ Christmas

Covid has taught us many valuable lessons. One of the most important is the need to live on a healthy planet with a healthy ecosystem. Climate change is real and caused by human action, as is biodiversity loss and air and sea pollution. All of these contribute to unsustainability. Everyone needs to be accountable for their own actions and habits. Christmas and New Year are traditionally the most ideal times to bring about change; that change could be living sustainably.

Conscious consumption

To be sustainable means to be able to maintain a balanced level of give and take. Right now, the planet is in an unsustainable state. We are currently using around 1.7 times what planet Earth can give. Overconsumption is a big player in this unsustainability and one of the forces driving the climate crisis. Many items are bought and consumed without thinking about a real need, especially during Christmas time. We are relentlessly driven into an over-consumption race with the excuse of gifting and celebrating.

Becoming a conscious consumer means that you put in thought and care before purchasing anything. Asking yourself questions such as: Where was this made? How did it arrive here? Who made it? Who or what suffered so that this product could be created? Celebrating a ‘green’ Christmas is possible when you choose eco-sustainable products. It means that the products were sourced, manufactured, produced, packaged, and transported with respect to the environment. An eco-friendly product is a product that was made with sustainability as a priority.

What is good for the planet is also good for people

Eco-sustainable products are those products which provide environmental, social, and economic benefits while protecting public health and the environment over their whole life cycle. If you care about what you put in — and on — your body and want to live a healthy lifestyle, choosing sustainable products is the way forward.

Choosing eco-sustainable options

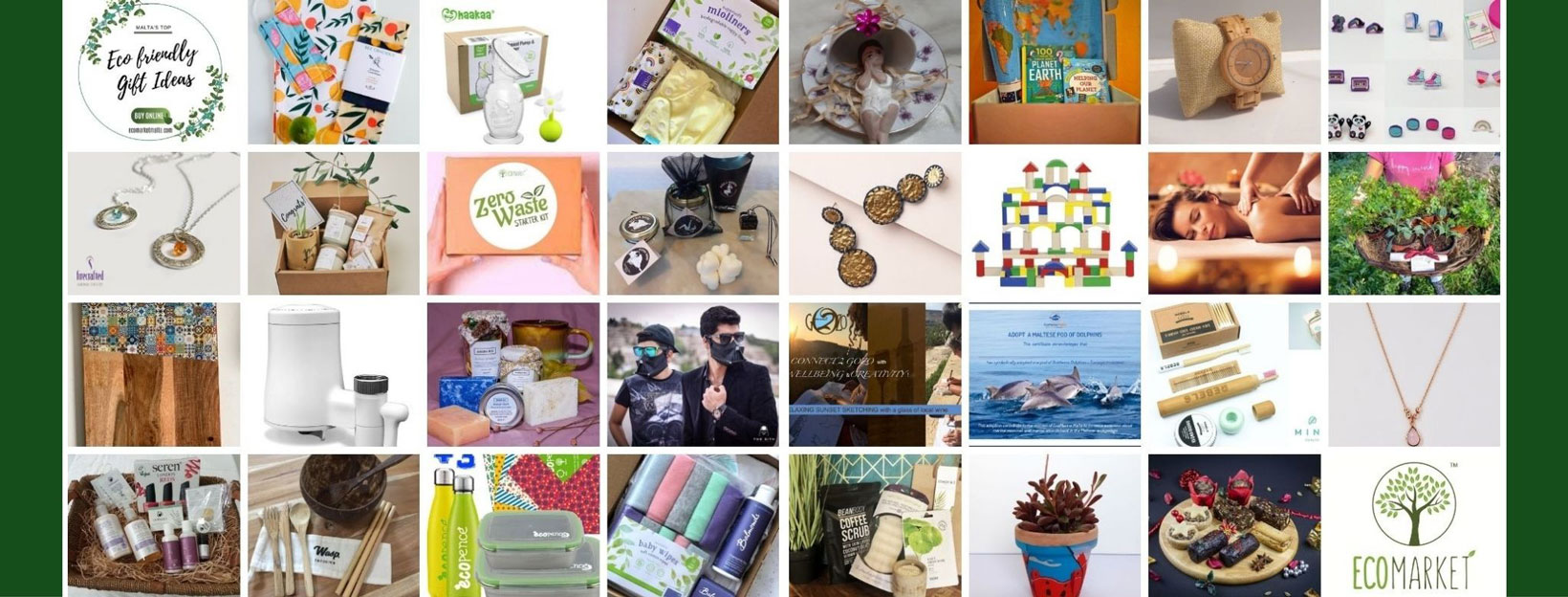

This year can end on a good note. Let us start taking responsibility for our actions and choose ethical and sustainable gifts for our loved ones, taking inspiration from Malta’s Top Eco-friendly Gift Ideas, a list created and curated by Eco Market Malta, a Social Enterprise advocating for UN Sustainable Development Goal #12; ‘Responsible Production and Consumption’.

The list contains a beautiful and well-curated collection of gift ideas from local green start-ups, artisans, and small to medium enterprises. Shopping local is a huge factor for sustainability, as it reduces the product’s carbon footprint. Many items are elegantly boxed but reduce plastic use, while others help people grow their own food, herbs, and flowers.

There are also several gift options for sustainable home appliances, such as jewellery, clothing, beauty, décor, wellness, children’s toys, gifts for new parents, and unique original ideas such as ‘adopt a dolphin’.

Be the change

Whether you are buying for an eco-conscious person or someone who is not yet environmentally aware, this list offers amazing gift ideas for everyone. As consumers, we can make a conscious choice to bring positive change into our lives, and since actions speak louder than words, your eco gift will also be a message inviting others to make their own positive impact. A meaningful and thoughtful gift can be more appreciated than a high-priced item. This year, let’s choose to shop sustainably and responsibly, avoid waste, be kind to the planet, and enjoy a simple and ‘green’ Christmas.

To view Malta’s top Eco-friendly Gift Guide please visit: ecomarketmalta.com.

This article is sponsored by EcoMarket Malta.

Quality Education for All

In today’s society, more than 262 million children and youth are not in school. To combat this, the United Nation established Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in order ‘to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all’ by 2030. One of these goals, SDG4, is on the importance of quality education, which inspired two art pieces created by Zarifa Dag and Martina Camilleri.

Both artists took part in a design competition organised by the University of Malta’s Faculty of Education, asking participants to submit creative designs inspired by the theme of SDG4, which focuses on inclusive and equitable quality education.

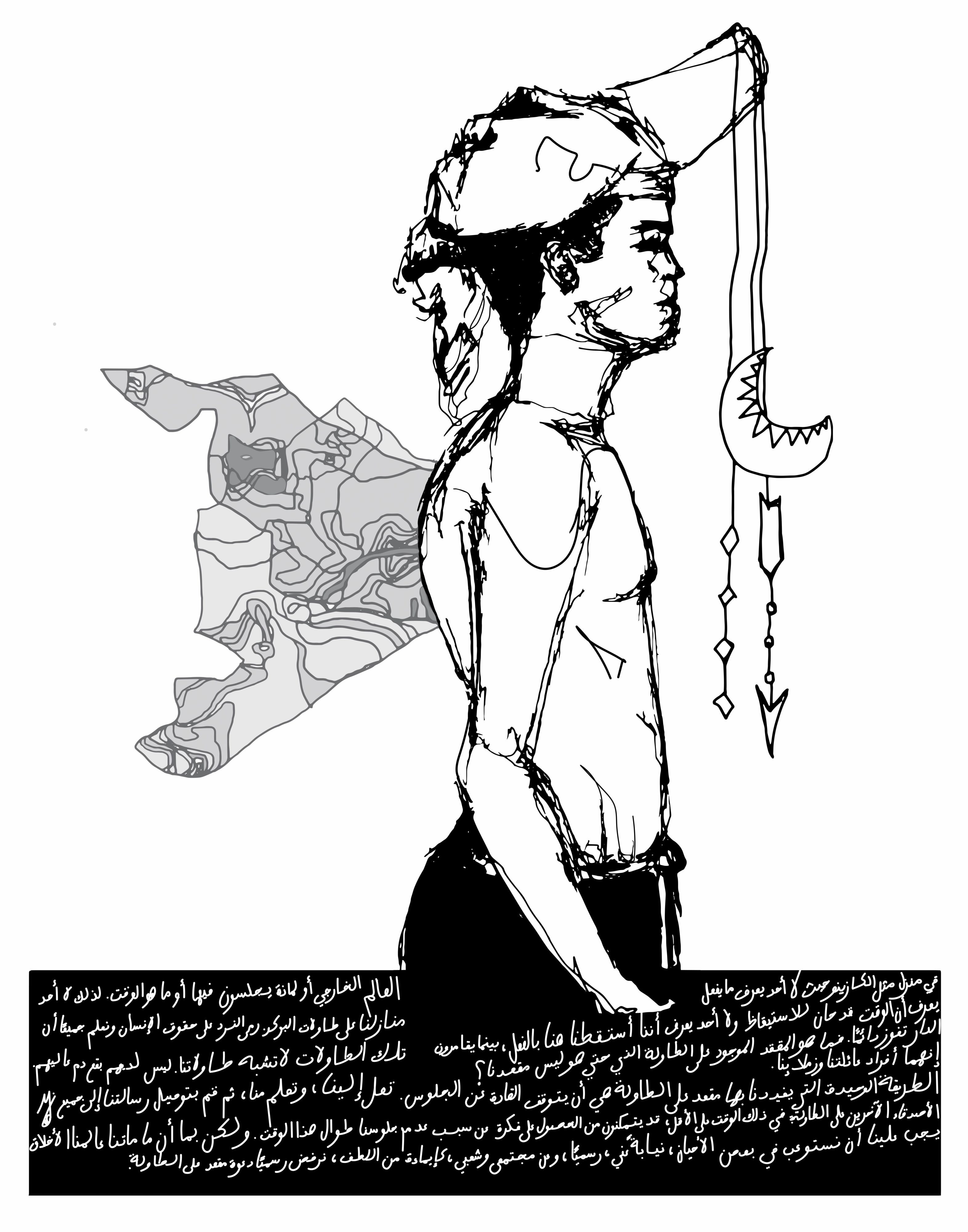

Zarifa has a background in graphic design and digital arts, and her submissions for the competition were heavily inspired by her dual cultural identity, as she has both European and Middle Eastern roots. She travelled to Lebanon in 2018 and volunteered in refugee camps, working with the children of immigrants who fled to Lebanon because of conflicts happening in countries like Syria. This experience allowed her to witness first hand the differences in quality of life and education between children in Malta and refugees.

Zarifa’s piece is titled Halep’te, which is Turkish for “In Aleppo”, referencing one of the major cities in Syria. Her illustrations centre around an adolescent, representing the younger generation and their future, as well as the people that are at the centre of SDG4. She brings in multiple cultural references through the turban (the Middle and Far East) and crescent (Islam). While her narrative begins with a somewhat bleak representation of the current situation in children’s education, it ends with an element of hope that the situation may improve.

Martina Camilleri, who is currently reading for a Masters of Art in Social Practice Art and Critical Education, presented her take on SDG4 and quality education through a piece titled En Root – a play on the term ‘en route’ – which explores the journey someone takes to get their education. For her first artwork, Seeds We Sow, she asked 40 participants about why they keep looking for education or teaching opportunities. She then photographed their hands and transferred the images onto wooden planks, writing their responses behind each individual plank.

Her second artwork, titled One Piece, consists of five distinct pieces made from ceramic and mixed media. They represent the five objectives outlined in the Universal Agenda towards quality education: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership. The pieces do not embody any of the terms individually. Instead, the art views the terms as a unified whole.

Zarifa and Martina’s artworks can be viewed along the main staircase of the Faculty of Education in the Old Humanities Building at the University of Malta. Although the artists interpreted the SDG4 in different ways, they both emphasised the importance of human-centred design. In essence, if somebody is going to use the product, then they should help construct it. The same approach could help achieve quality education for all children, despite socio-economic factors.

Ilħna mill-imgħoddi

Biex taqra l-artiklu bl-Ingliż, agħfas hawn.

Kaxxi fuq kaxxi, miksijin bl-għabra, jistennew is-sekondiera tagħmel ir-ronda tagħha. Is-sekondi jsiru minuti. Isiru sigħat. Ġranet. Xhur. Snin sħaħ. Deċennji, sewwasew.

Il-Prof. Edward Fenech wirithom mingħand il-Prof. Ġużè Aquilina, imma ġara li l-kaxxi u ta’ ġo fihom ingħataw il-ġenb għal ħafna żmien. Parti ġmielha mill-istorja lingwistika u kulturali tagħna konna bil-mod il-mod qed nitilfuha minn taħt imneħirna.

Mistura fil-kaxxi nstabu r-reel-to-reels li l-Prof. Aquilina, missier il-Lingwistika Maltija, kien uża biex jimmortala l-ilħna bil-kisra djalettali ta’ bosta kelliema minn lokalitajiet differenti f’Malta u Għawdex.

Illum, kulma jmur qed nagħrfu u napprezzaw il-ġmiel ta’ mużajk li jsawru d-djaletti tal-gżejjer Maltin. Iżda, sa ftit snin ilu, min jitkellem bid-djalett aktarx li kien jitqies ta’ klassi baxxa. Ħtija tal-preġudizzju, xi wħud ippruvaw jinfatmu minn dan l-aspett ewlieni tal-identità kulturali tagħhom. Il-preżenza tad-djalett qajl qajl bdiet tiddgħajjef. In-nies tħalltu fiż-żwieġ, u magħhom tħalltet il-lingwa. Min mar joqgħod f’raħal ieħor kien espost għal djalett differenti, u t-tfal bdew imorru l-iskola u jitgħallmu l-Malti standard, ‘il-pulit’, sajjem minn xi karatteristiċi li jżewqu t-taħdit.

Il-Prof. Aquilina minn kmieni għaraf li ħaġa daqstant sabiħa ma kellniex nerħuha tiżolqilna minn idejna (jew ħalqna f’dan il-każ), u fis-snin sittin u sebgħin, irħielha lejn xi rħula Maltin u Għawdxin, idur bir-reel-to-reel recorder, jitħaddet man-nies dwarhom infushom, dwar is-snajja’ tagħhom, u dwar it-tradizzjonijiet li wirtu bil-fomm u bl-id. Bil-mikrofonu kien qed jaqbad il-ħsejjes u l-forom tad-djaletti, imma mhux biss. Ma’ kull intervista, kien qed jiddokumenta stil ta’ għajxien li llum jinħass tant ’il bogħod. Bl-għajnuna ta’ Benedikt Isserlin mill-Università ta’ Leeds ġabar 92 audio file b’madwar 50 siegħa taħdit djalettali, mhux kollu tal-istess kwalità. Bil-materjal miġbur, Aquilina u Isserlin fl-1981 ħarġu pubblikazzjoni li tittratta elementi fonoloġiċi tad-djaletti. Daqs tletin sena wara, John Paul Grima sema’ l-audio files wieħed wieħed, u b’reqqa kbira ddokumenta u kkataloga l-ħidma fit-teżina tal-Baċellerat tiegħu.

Fost l-ilħna li ltaqa’ magħhom Aquilina, hemm tal-iskarpan mill-Għarb, li, hu u jmertel il-ġild, jispjega l-proċess tal-ħjūta bl-aktar ġild fin Ingliż. Tħaddet mal-għaġġiena mix-Xagħra, li tispjega kif ħobża titwieled mid-dqiq, tingħaġen u tinħadem sakemm issib ruħha fuq it-tilar, lesta biex tinħema. Tkellem mar-raħħala Żurriqija fuq kif iġġiżż in-nagħġa biex tħaffilha s-suf, fuq nagħġa żgħira li għad ma kellhiex ħaruf (għabura), u n-nagħġa li qatt ma kellha (ħawlija). Skopra kif ix-Xlukkajri jaħslu l-ħwejjeġ bl-ilma salmastru fil-Fawwara tal-Ħasselin, u sema’ kif tinħadem u titħejjet il-bizzilla f’Ta’ Sannat, skont il-bixra li l-lingwa tieħu f’kull post.

Dan il-materjal prezzjuż inżamm f’kaxxi li maż-żmien għoddhom intesew. Kien b’kumbinazzjoni li wara ħafna snin ir-reel-to-reels sabu ruħhom fl-istudio ta’ Anthony Baldacchino. U minn hemm, fuq l-inizzjattiva tal-Prof. Alexandra Vella, beda l-proċess biex il-materjal maħżun fihom jiġi ddiġitalizzat. Xejn ma kien faċli li l-kontenut tar-reel-to-reels l-antiki jinqaleb f’format diġitali. Illum, l-ilħna tal-imgħoddi f’dan il-format, ftit ftit qed jittellgħu fil-portal tar-riċerka malti.mt, li d-Dipartiment tal-Malti se jniedi fix-xhur li ġejjin, ħalli jkunu aċċessibbli għall-istudjużi u għal kull min għandu interess fid-djaletti, is-snajja’ tradizzjonali, u b’mod ġenerali l-ħajja fl-ewwel snin ta’ wara l-Indipendenza.

Bis-saħħa ta’ dan il-proġett, ikkoordinat mill-Prof. Alexandra Vella, il-Prof. Ray Fabri u Dr Michael Spagnol, dan il-felli tal-istorja tagħna jista’ jitgawda mill-pubbliku u jiġi studjat mir-riċerkaturi ħalli nifhmu aħjar il-qagħda lingwistika tant rikka fil-gżejjer żgħar tagħna. Għax dawn l-ilħna jsawru ħolqa f’katina li tixhed li, għalkemm minn fuqhom m’għaddewx aktar minn ħamsin sena, il-ħsejjes, ir-rakkonti, l-għerf u d-drawwiet li fihom inewlulna pinzellati minn ħajja li m’ilha xejn imma ilha ħafna.

What did the Past Sound Like?

The way Maltese sounds has evolved over the decades. While written examples of Maltese have survived, records of how it was spoken are much more scarce. However, thanks to the efforts of Prof. Alexandra Vella (UM), Prof. Ray Fabri (UM) and Dr Michael Spagnol, we now have the opportunity to hear firsthand what Maltese sounded like 60 years ago!

Continue reading