The prehistoric Megalithic Temples found around Malta were once home to an ancient civilization. We have no records of how their spirituality was practised—only limited archaeological evidence. However, conducting an anthropological study of contemporary Neopagan communities may provide insight into the rituals of these mysterious people.

Many are surprised to learn that there are Neopagan communities scattered throughout Malta, many of whom look to the Neolithic past as a source of inspiration.

It is important to first clarify what Paganism is. To begin, it is not an organised religion: beliefs of individual practitioners vary widely. As in Buddhism, adherents may also be Roman Catholic, Jewish, atheist, and so on. Some Neopagans believe in pantheons of deities; others are agnostic practitioners who only consider ‘gods’ to be symbolic archetypes. Similar to shamanism, Pagan practices often involve trance-evoking meditation, music, and movement. There is no set hierarchy or dogma. Rituals are as varied as the organisers’ talents.

Maltese Pagan History

Paganism has a rich history on the Maltese islands. From 5,900–2,500 BCE, Malta’s Late Neolithic Civilization created a rich cosmology, as evidenced by the temples and artefacts left behind. Later, Bronze Age visitors, Phoenicians, and Romans who settled in Malta also brought with them their own Pagan gods, goddesses, practices, and beliefs.

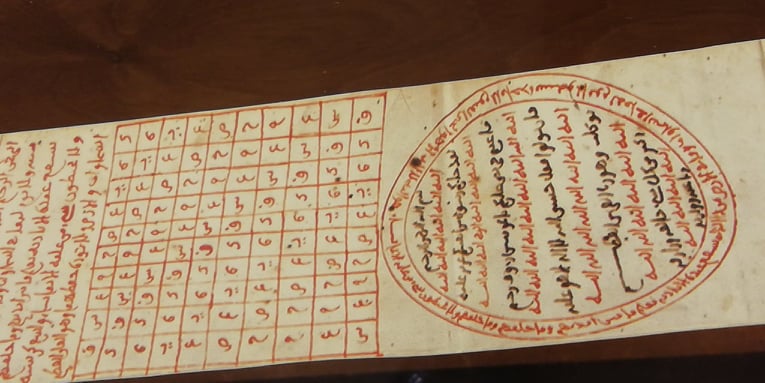

Throughout the early modern era, undercurrents of Paganism were retained, even if practitioners were monotheistic. One Muslim slave, Sellem bin al-Sheikh Mansur, was imprisoned by the Roman Inquisition for practising geomancy (a form of divination). His student, Vittorio Cassar, a Knight of the Order of St. John, also suffered run-ins with the Inquisition for fortune-telling. Today, an exhibit at the Grand Inquisitor’s Palace showcases ‘magical spells’ from this era, including one inscribed upon a paper hat for headaches. Two-hundred years later, Grognet de Vassé, architect of the Mosta Dome (and proponent of the Malta-as-Atlantis hypothesis), modelled its structure on the Pantheon of Rome, a once-renowned Pagan site.

In the 1920’s, archaeologist Margaret Murray visited Malta to excavate while authoring a text that became a foundation for modern Paganism. She argued that a cult in Europe worshipping a female goddess and male god had been present since prehistoric times. Anthropologist Gerald Gardner built upon her work and in the 1930’s spread the new philosophy of ‘Wicca’, a spirituality incorporating worship of feminine and masculine deities. His influential 1954 book forms the bedrock of today’s Neopaganism, which later reached Malta’s shores by the 1970’s. In the 1990’s, Starhawk pushed the practice towards ecofeminism, and Scott Cunningham presented Wicca as a paradigm of radical modernity. Concurrently, Marija Gimbutas popularised Malta as a site of ancient goddess worship. Today, this 21st century progressive ideology attracts many, and the temple sites of Malta are still a Mecca for the movement.

The Feminine Divine

For many Maltese Neopagans, their relationship to Malta’s prehistory is intimately tied to the era’s famed statues, often considered embodiments of a primeval Earth Mother or ‘’The Goddess’. Today’s altars often highlight Neolithic figurines such as ‘The Venus of Malta’ or ‘The Skorba Goddess’, placed there as evocations of the ancient past. Such presentation of sacral objects may reflect rites from millennia past.

Honouring this feminine-divine, especially as ‘Gaia’, the embodiment of nature, is an element that binds many of the tribe together. Kirsten Saliba notes in her 2018 ethnography of Malta’s Neopagans, such worship empowers women ‘to look at themselves as divine, their bodies as sacred, and the evolving phases throughout their lives as holy’. As Anna, one Neopagan states: ‘She is the land itself; Malta itself; climate itself’. Men, too, have found the worship of ‘The Goddess’ to be a source of inspiration. Adam believes that ‘She restores something that has been robbed from us in the West, and returns a wholeness to the broken worldview that we have inherited’.

Neolithic Inspired Rituals

Today, Maltese Pagans often enter the ancient structures in an effort to experience transcendence. For Adam, walking amidst the temples in bare feet is a recognition that we tread upon holy ground. When Steve enters a site, he ‘connects’ with stones to render the barrier between the material and spiritual worlds ‘porous’. His partner, Br’er expresses similar sanctity. For him, the juxtaposition of unchanging rock with the ever-changing soil is a dance.

In 1990, Veen, a cultural anthropologist, collected such historical accounts of rituals. She documents those at the Stone of Qala in Gozo, where women who wished to become pregnant encircled and sat upon the megalith.

Today, this stone is still a focal point for Neopagans. In a recent ceremony, broad beans were placed around the stone, a homage to the legendary Maltese giantess who was believed to have lived off such beans. Such rites may echo the prehistoric past, where excavations have shown possible food offerings at the temple sites.

The enigmatic spiral is characteristic of the Maltese Neolithic, and many Maltese Neopagans still resonate with the symbol. Adam recounts how within the Hypogeum, a water droplet once significantly fell in the middle of his forehead, so he traced a spiral with it. For Aiden, the shape represents the ‘eternal cycle’. For Celaeno, it is the dance between life and death.

The spiral also forms a basis for sacred dance. During Samhain (the Pagan celebration that falls near Halloween), Anna, Ivy, and Celaeno all participated in a joyful, impromptu ‘widdershins’ around a bonfire. Perhaps such movements are similar to those practiced by the ancient Maltese.

Fighting Stigma

Although Malta’s Pagan communities are growing, there are challenges. Adam argues that accessibility is needed for those who wish to worship within the ancient temples. ‘The spiritual approach shouldn’t be seen as fringe, but as a valid way of approaching these sites.’

Others feel stigmatised by misinformed beliefs that they are a cult, out of touch with reality, or ‘follow the devil’. Several live in fear of such judgment.

Ivy and Aiden both expressed experiences of castigation. Ivy’s parents, upon discovering some jewelry with pentacles and moons, became convinced that their daughter was worshipping Satan. They couldn’t understand that she simply worshiped nature. Likewise, Aiden described waking from nightmares where Pagans were persecuted by modern day forces.

A few years ago, a Mater Dei Hospital nurse accused an expectant Pagan mother of being a ‘Satanist’ after seeing her pentacle tattoo. They called in a priest to ‘bless’ the areas of the hospital that the patient had ‘contaminated’. As Rountree noted in 2016, such antiquated thinking is ‘evocative of eighteenth-century witch-hunts’ and leaves Malta’s Neopagans vulnerable. Sarah makes the emphatic argument that acceptance is needed. As she extolls, ‘We are good people.’

Pagan Activism

Maltese Pagans are also deeply upset by reckless environmental and archaeological destruction. Some wishing to protest against the over-development and commercialization of ancient landscapes formed Malta ARCH. In 2017, they rallied around the battle to save Tal-Qares, a Roman site. One member created an installation featuring a supermarket shelf of rusting cans etched with Neolithic symbols to signify its devastation.

Although they lost the battle to save Tal-Qares, they did win a significant victory protecting the archaeological site of Tal-Wej from development. This ignited the hope in many of becoming a political force, one born of a subversive ‘Spiritual Revolution’.

The Future

Although there are some profound differences between competing Maltese Neopagan groups, they are all united in their wish to empower their community and create safe, inclusive spaces. Crucially, they teach acceptance and respect for all humanity—particularly the marginalised—through their creative, eco-friendly, and female-centric practice. All want the acceptance and respect that their Northern European counterparts enjoy—and they deserve it.

Names have been changed

Further Reading

Rountree, K. 2016 Crafting Contemporary Pagan Identities in a Catholic Society. Burlington: Ashgate.

Saliba, K. 2018 Nature, Femininity and the Sacred: Constructing Spirituality in Catholic Malta. A dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts, University of Malta, in part-fulfillment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Anthropology.

Veen, V. 1990 Female Images of Malta: Goddess, Giantess, Farmeress. Haarlem: Inanna-Fia.

Comments are closed for this article!