Artist Matthew Attard uses eye-tracking to spark intriguing conversations, challenging us to see the world through new eyes and explore the intersection of art and activism.

When I was teaching art, students would come up to me to say how they had an image in their heads that their hands couldn’t really translate onto paper. But what if you could draw using only your eyes?

Well, eye-tracking technology can’t really create a perfect image; however, for artist Matthew Attard, they do lead to some fascinating questions about the nature of art and social activism.

Cast off!

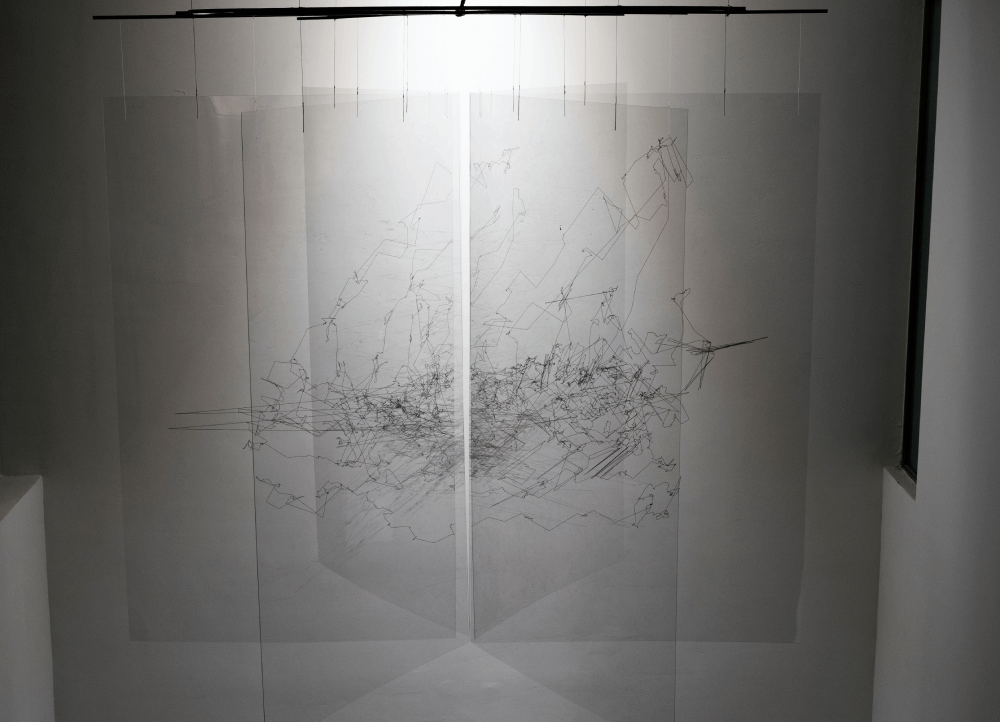

Waiting for me just outside the Valletta Contemporary, I met Elyse Tonna, the curator behind the Rajt Ma Rajtx… naf li rajt exhibition. After a warm greeting we head inside, and immediately my eyes are drawn to 6 large perspex screens hanging from the ceiling. Looking up from below, the screens are set about 60 degrees apart from each other, forming what looks like a ship’s helm.

At first glance, straight lines criss-cross the perspex screens like a tangled net. But the more I focus on the lines, a rough outline of a corsair ship begins to form like a magic eye picture: the lonely masts standing tall, the shoulder-of-mutton sails, and the prow.

‘It’s like doodling with the eyes,’ Tonna explains.

Doodling with the eyes

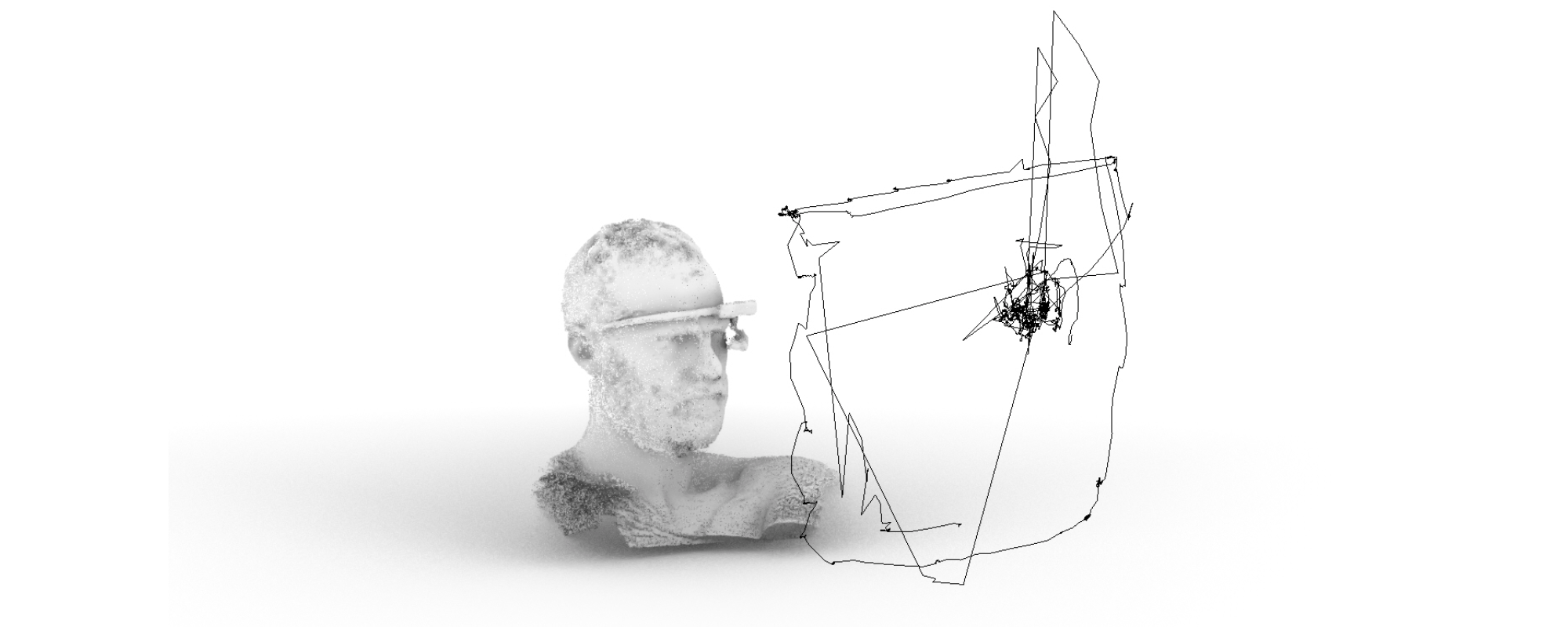

Matthew Attard, the artist behind the exhibition, uses an eye-tracker to make his art. It’s the first art of its kind. The eye-trackers function like a pair of glasses which are calibrated to record eye movement. The tracker ‘observes’ where Matthew’s eyes go and plots those points. Matthew explains how the tracker records footage of his eye as well as his view. ‘The points are then exported as raw data through its software, after it estimates my eye movements. I then use 3D software to develop these into a drawing, and eventually some are projected as video, others are digitally printed, and some are drawn with a pen-plotter.’

In an adjoining room, a complimentary exhibition, Ħars fuq ħars (roughly translated to Looks upon looks) curated by Margerita Pulè, is taking place. Artists were asked to look at one of their own artworks and gaze at it creatively through an eye-tracker. This footage was recorded and superimposed on their art. Seeing how the artists’ looked upon their own art suggests how multifaceted and personal the act of looking can be.

Seeing is believing

Going back to Matthew’s exhibition, Rajt ma rajtx … naf li rajt translates to I/you saw, but I/you did not see… I know that I/you saw. The original phrase in Maltese suggests a code of silence, usually uttered in whispered tones and accompanied by a mischievous wink when turning a blind eye to impropriety. Perhaps the closest analogy would be the three monkeys, ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.’

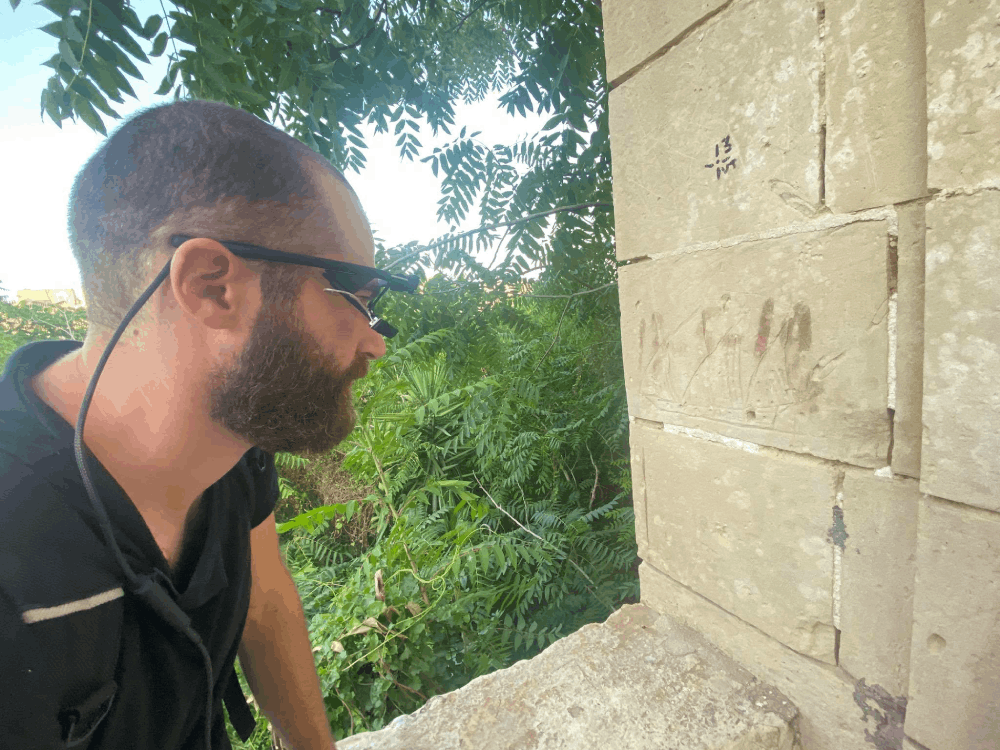

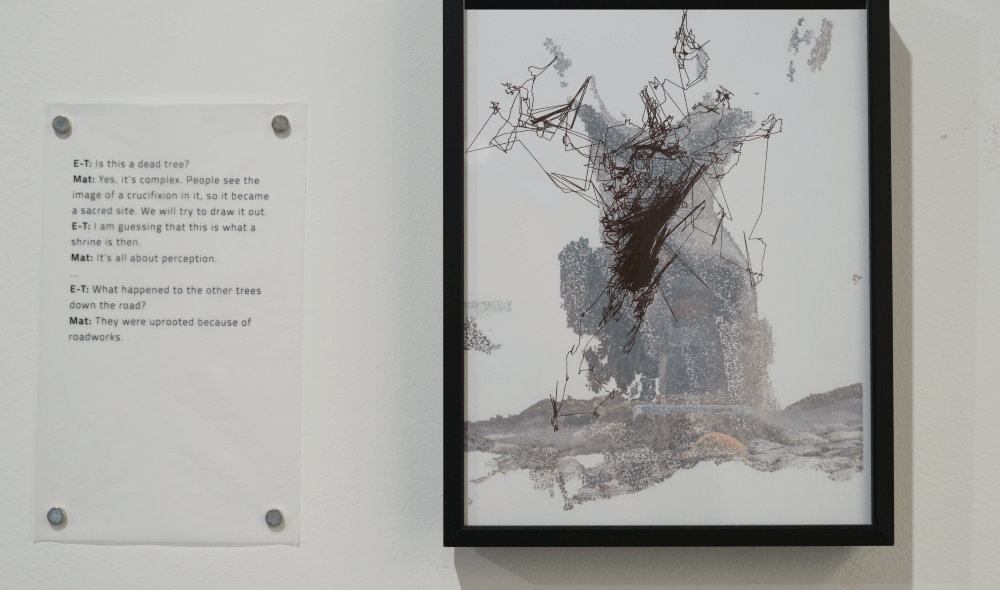

While we can choose to turn a blind eye to injustices around us, the eye-tracker does not. In fact the eye-tracker, personified as an inquisitive entity trying to understand human culture, acts as a foil to our willful ignorance. It points out inconsistencies or abnormalities in the way society acts, inviting us to reflect. For Matthew, this opens a dialogue with technology which he playfully presents alongside the various exhibitions. One of these dialogues accompanies a sketch of the ‘Crucifix Tree’ in Rabat;

Eye-Tracker: Is this a dead tree?

Matthew: Yes, it’s complex. People see the image of a crucifixion in it, so it became a sacred site. We will try to draw it out.

Eye-Tracker: I’m guessing that this is what a shrine is then.

Matthew: It’s all about perception.

Eye-Tracker: What happened to the other trees down the road?

Matthew: They were uprooted because of roadworks.

The Ship of Fools

Besides opening the question on the role of technology in art, Matthew’s exhibition presents us with a more politically charged question. ‘You cannot lie to the eye-tracker, likewise you cannot lie about what’s happening around us,’ Elyse explains. The eye-tracker presents, with scientific indifference, what is ‘actually’ there. If you decide to act upon it, it’s up to you.

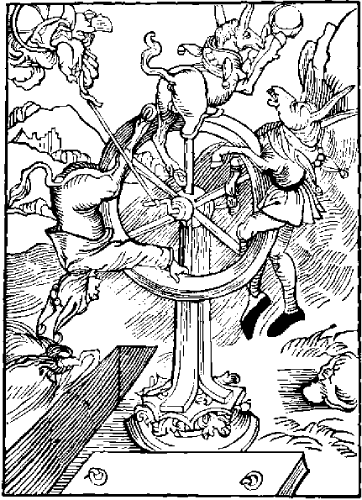

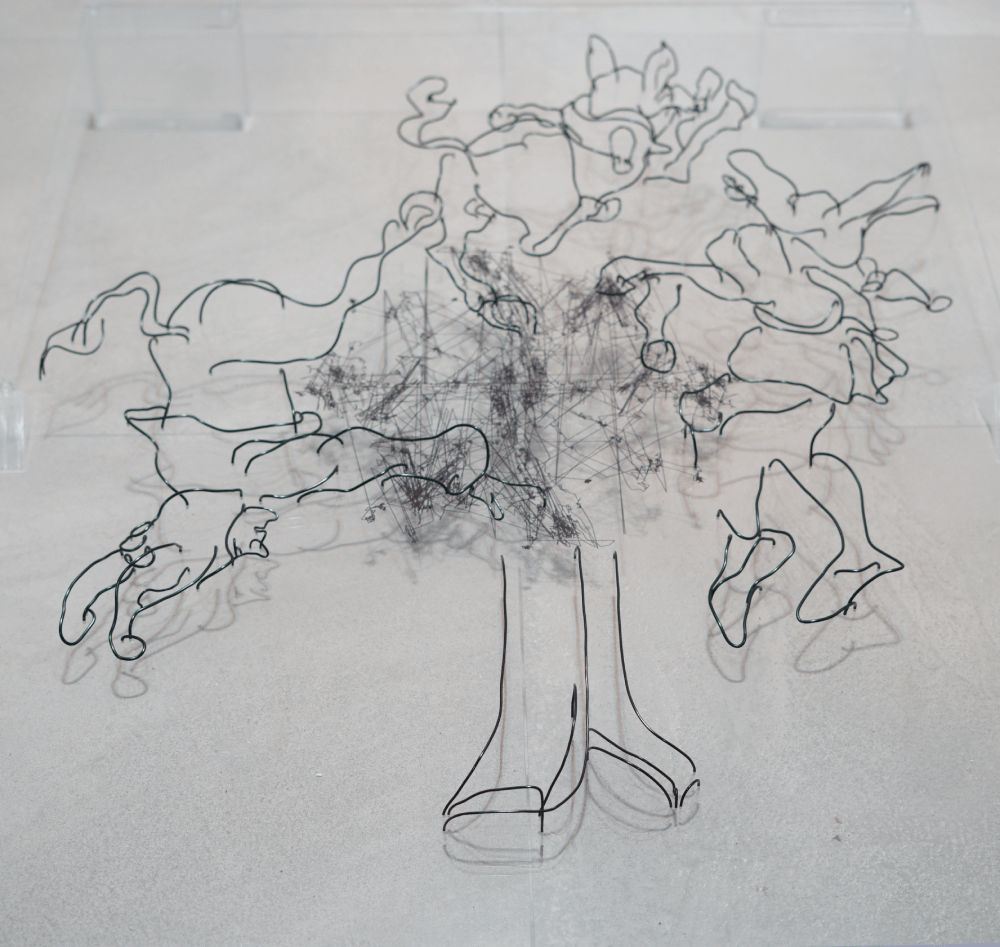

Underneath the floating ship, another perspex screen lies flat on the floor. This time, the mesh of points and straight lines are surrounded by the outlines of donkeys and a court jester.

‘It’s based on an attributed image of Albrecht Durer’s illustration in the Ship of Fools,’ Tonna explains. The ship of fools is an allegory by Plato presenting the problems of governance that is not based on expert knowledge. There’s a delicious irony when one translates this into Maltese. The Maltese translation for fool, ‘fidil’ has a double meaning. It could refer to being faithful or being an idiot.

For Matthew, ‘the allegory was just a starting point from which to delve into a different commentary, starting by re-working the title into: Id-Dgħajsa tal-Fidili.’ Besides being a fool, the ‘fidil’ is consumed by blind faith and willfully ignores what happens around them. While they might witness an injustice, they do not actually see it, nor do they act upon it. It is a sobering reminder that while we can lie to ourselves about what we’re seeing, we need to make an active choice to act upon it.

While we can choose to ignore the stinging barbs of art, there is no hiding from what is actually there. We may sweep our concerns under the carpet or try to salvage a sinking ship. In the end, it is history and our children that will judge whether we were fidili or not.

Comments are closed for this article!