For the price of a coffee

The global pandemic is a further blow to already struggling local media. Prof. Mary Anne Lauri, media researcher and Editorial Board member at Beacon Media Group, unpacks this trend.

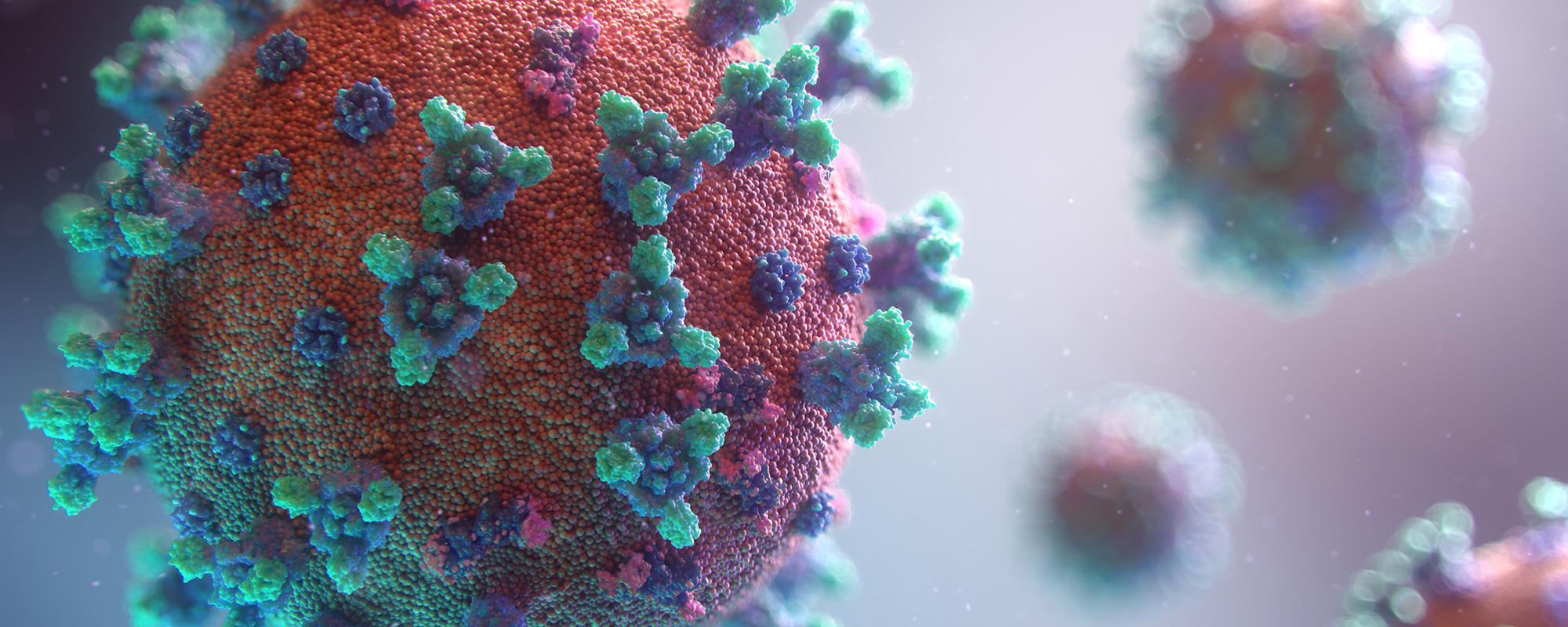

Continue readingSocial networks to support mental health

The COVID-19 situation has taken a toll on people’s wellbeing. The constant flow of information can amplify the stress. Dr Josianne Scerri and Dr Paulann Grech, together with their colleagues and students, carved out a space on social networks where people could practise self-care – and get their facts right. They share their experience here.

Continue readingCoronanomics in Malta

In 2019, 2.8 million tourists came to Malta and spent on average over €800 each. Maltese households spent in total €826.8 million on eating out and takeaways in 2018. In March 2020, the COVID-19 global pandemic arrived in Malta. Subsequent containment measures swept most of this spending away. Prof. Joseph Falzon crunches the numbers of the predicted economic impact.

Continue readingUnmute yourselves!

COVID-19 pandemic containment measures pushed lecturing and studying to home environments. Some academics appreciated it more than others – they share their experience with editor Daiva Repeckaite.

Continue readingCOVID-19 Crisis: have we done this before?

Popular wisdom warns that those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it. Will the current COVID-19 pandemic prove the adage true? Cassi Camilleri writes.

Continue readingWhen trust is lost in translation

Author: Marcelle Bugre

Social workers are in close contact with people; it’s the nature of their job. But when migrant survivors of domestic violence seek help, they often perceive social workers to be representatives of a more powerful group. Thus, survivors may be wary of trusting social workers, or fear losing their children, being reported to immigration authorities, or blamed for what happened. To engage with a growing number of migrants and minorities today, social workers need cross-cultural competence – the ability to work effectively across cultures.

Continue readingReorganising space for the climate emergency

Author: Miguel Azzopardi

Merely counting greenhouse gas emissions will not address climate change. The solution is closer than we think: our own use of space. Look at land use: switching to a flexitarian, vegetarian and vegan diet is one of the greatest individual contributions. To produce meat, the industry puts heaps of land aside for animals and their fodder. Plant-based diets would mean less land is used for agriculture. Economising space can apply to other areas.

Our transportation model is heavily dependent on car usage. Segregated bus and cycle lanes are rare in Malta, even if these modes of transport allow more people to travel using the same space. Car-pooling in Malta is picking up, but not yet mainstream. COOL is one example of car-pooling initiatives that are slowly gaining traction. Various eNGOs, like Extinction Rebellion Malta, are lobbying for the government to further incentivise public transport. This way, there would be no need to sacrifice agricultural land for road-widening and car-mania. Instead, Malta could start looking into reforestation and rewilding.

Our approach to urban planning would benefit from environmentalist reorganisation. In Malta, developers enjoy a free-for-all. Numerous charming one- or two-storey buildings are choked by neighbouring high-rises. In some instances, people have installed solar panels on their roof only to have them covered by shade. Shade has wasted away gardens and affected mental health — all on a sunny Mediterranean island. Proper planning would allow more uniform streetscapes, urban greening and better utilisation of roof space. The environment minister Aaron Farrugia’s ‘green revolution’ should encompass all planning on the Maltese Islands.

Land reclamation has been proposed as a possible solution to Malta’s limited space. The process does not create space, it repurposes space that already exists. In Malta, this means more environmental destruction as we bury natural habits like meadows of protected seagrass (Posidonia oceanica), which are also valuable carbon sinks. Reclamation is not an option due to the climate crises and widespread presence of Posidonia around our shores. We should be protecting and restoring natural habitats, not destroying them.

Maltese authorities have ignored spatial planning suggestions. Faced with the crisis, Malta needs to acknowledge that if we want to meet ambitious climate emission targets we need to have coherent planning policies and direction that give the environment the priority it deserves.

Miguel Azzopardi is a history student at the University of Edinburgh and an activist with Extinction Rebellion Malta.

Subtitling against exclusion in Malta

Author: Luisa Castorina

Imagine watching a documentary or movie without hearing any voices, background noises, and music. You would miss a source of entertainment and information, and be excluded from conversations around movies and TV series. How annoying and frustrating would that be?

Continue reading