Assisted Conception — IVF and other procedures

Assisted conception procedures arose as a type of treatment for infertility. They opened a whole new range of possibilities for couples that were unable to have children due to a variety of problems. Initially, the difficulty addressed was of blocked or absent fallopian tubes in women. This prevented the oocyte from making contact with sperm, hence preventing the formation of an embryo. Naturally, this also prevented an embryo from moving into the uterus, implanting itself, and developing into a foetus.

In vitro fertilisation bypasses tubes by obtaining oocytes from the ovaries and fertilising these oocytes outside the body (in vitro — in glass). The procedure became a reality in humans with the pioneering work of Steptoe and Edwards and the delivery of Louise Brown in 1974. She gave birth naturally in 1999.

“In our society, infertility is becoming more common and 8 out of 10 couples can experience problems”

With the further development of ICSI (Intra cytoplasmic Sperm Injection) it was possible to fertilise an oocyte (egg) with an individual sperm. This was a breakthrough therapy for men with low or absent sperm counts.  When sperm are lacking in the ejaculate, a doctor can retrieve them directly from the testicles, or the epididymis (a tightly coiled tube from the testes to the rest of the body). The procedure is known as TESA or PESA. In combination with ICSI, these techniques made it possible for these men to father children.

When sperm are lacking in the ejaculate, a doctor can retrieve them directly from the testicles, or the epididymis (a tightly coiled tube from the testes to the rest of the body). The procedure is known as TESA or PESA. In combination with ICSI, these techniques made it possible for these men to father children.

In our society, infertility is becoming more common and 8 out of 10 couples can experience problems. This simple statistic makes these procedures increasingly important. Nowadays, even couples with the most severe problems can become parents.

These procedures have been mixed in controversy from the beginning, with most countries allowing science to proceed within certain safeguards. This restrained approach allows for progress.

Regrettably, infertility still carries a large stigma. The thousands who have benefited from these and other simpler infertility procedures (they precede attempts for assisted conception) do not speak out. Normally they don’t because of how society would perceive them or their children.

IVF is a physically, psychologically, and financially demanding procedure. Couples normally only proceed after having spent a considerable time beforehand seeking help, investigating, and trying alternative simpler treatments. It is usually the final recommended solution to the problem.

IVF essentially means that fertilisation of the oocytes occurs out of the body. The oocytes are then fertilised with sperm and in a percentage of cases this is successful and an embryo starts to develop.

This article continues the focus on IVF from last year’s opinion piece by Prof. Pierre Mallia. Other local experts have been contacted and we are open for further opinions and comments from our readers.

Discovering Depression Treatments

Over 100 million people suffer from depression. Prof. Giuseppe Di Giovanni talks about his life’s work on the brain chemical serotonin to find a new treatment for this debilitating disease that touches so many of us

The winter rays of sunlight reflected off the snow upon Mount Maiella and the beautiful Adriatic Sea. They lit up the room where I was sitting with Dr Ennio Esposito (head of the Neurophysiology unit, Mario Negri Sud, Italy). On this cold day in February the light was blinding and it was difficult to make out my long time friend and colleague. Together we had studied the brain chemicals serotonin and dopamine vital for love, pleasure, addiction, and linked to depression — my research subject.

‘Ennio, I am tired and frustrated, I am increasingly convinced that our in vivo (whole organism) experimental approach is not the right one. There is too much variability in the results and if we really want to understand the cause of depression and find a new cure we need to get some reproducible data and change our tactic.’

“We still do not understand how many psychoactive drugs actually work, meaning that more research is needed”

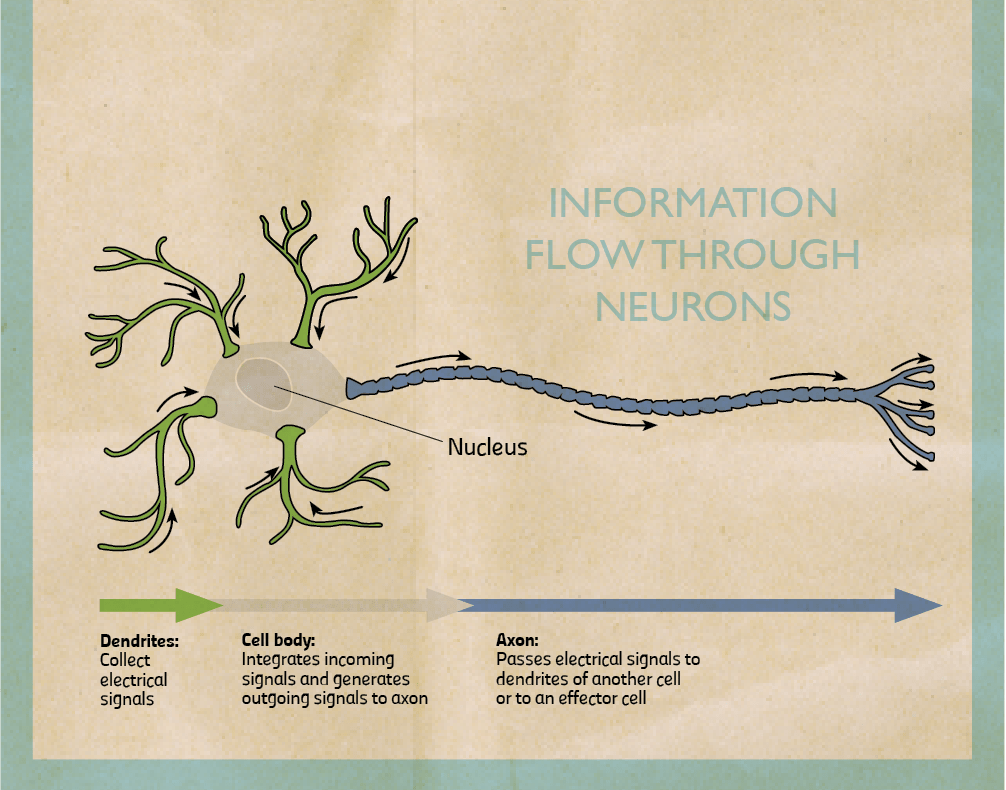

At that time, I was using glass electrodes to study changes in the electrical activity of single neurons in brains. Additionally, I used a technique (microiontophoresis) that registers neuron electrical activity and also applies a very small amount of the drug. In this way, I could see which brain cell was active and how different chemicals might influence it. Surprisingly, though introduced in the 1950s, these techniques are still some of the best ways to study drug effects on a living brain.

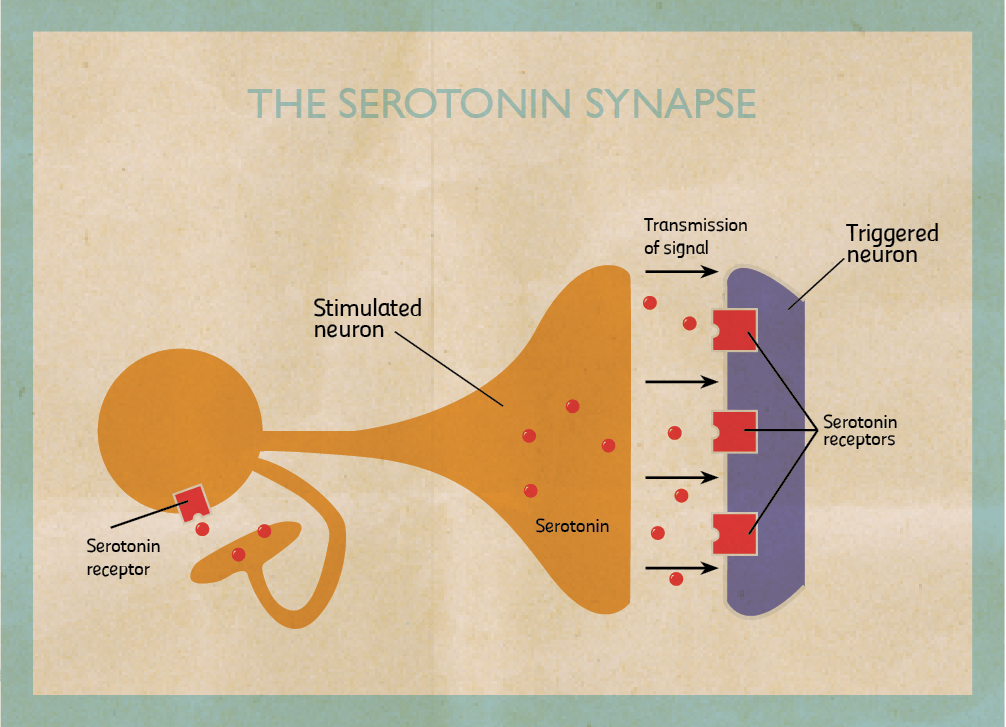

My research focuses on the role of two brain chemicals, dopamine and serotonin, in mental disorders. When stimulated neurons release chemicals (neurotransmitters). I am interested in dopaminergic neurons which release dopamine and serotonergic neurons that release serotonin. Once released, chemicals can pass through the spaces in between neurons and bind to another neuron stimulating or inhibiting it. They bind on proteins called receptors. When they do, they trigger the cell to fire or shut down. By triggering certain neurons in our brains, they reinforce or change our behaviour.

Dopamine is involved in the pleasure pathway. It switches on for behaviours like emotional responses, locomotion, and reinforcing good feelings. Changes in the level of dopamine effect a person’s reward and curiosity-seeking behaviour, like sex and addictive drugs. On the other hand, serotonin seems to have a more subtle role. One of serotonin’s major roles is to modulate or control the effects of other neurotransmitters, such as dopamine. In the words of Carew, a Yale researcher, ‘Serotonin is only one of the molecules in the orchestra. But rather than being the trumpet or the cello player, it’s the band leader who choreographs the output of the brain.’ The belief that serotonin is the brain’s ‘happy chemical’, that low serotonin levels cause depression and antidepressants work by boosting it is a very simplistic view. In truth, no one knows exactly how dopamine and serotonin levels induce depression.

“I have spent my life trying to figure out the role of dopamine and serotonin in the brain”

A lot of what we do know is because of animal research. The animals used to model this disease are given antidepressants to try and understand how effective they are and how they work. By studying their brains we can start to comprehend what causes depression. Right now we do not understand the whole picture behind the causes of depression and patients end up receiving inadequate treatment. We still do not understand how many psychoactive drugs actually work, meaning that more research is needed.

Most drugs were discovered by chance while being used to treat other disorders. For example, the antidepressant Iproniazid was originally developed to fight tuberculosis.

After the researchers saw less depression in patients suffering from tuberculosis they started prescribing it to depressed patients. In another example from the 1950s, clinicians discovered the first tricyclic antidepressant while searching for new drugs against other mental diseases.

Today, we fortunately have a battery of drugs that can treat depression. Unfortunately, the best drugs on the market only completely alleviate symptoms in 35 to 40 percent of patients compared to 15 to 20 percent taking a placebo (a sugar pill), a fact not publicised in pharmaceutical ads. Another problem is that when people begin taking antidepressants, mood changes can take four weeks or more to appear. This delay in action is one of the major limitations of these medications since it prolongs the impairments associated with depression, increases the risk of suicide, the probability that a patient stops treatment, and medical costs. To tackle these problems pharmaceutical companies and academic researchers want to find more effective and faster acting antidepressant drugs.

Ennio and I, together with Vincenzo Di Matteo and other researchers at the Mario Negri have tried to resolve the antidepressant lag time enigma by studying rats. We first inhibited the levels of serotonin for 3 weeks using the latest Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) named fluoxetine, sertraline, and citalopram. Then we measured the electrical activity of dopamine and serotonin neurons in rat brains. We discovered that the therapeutic effect of antidepressants is not only due to their capacity to restore a normal level of serotonin activity. It also induces adaptive mechanisms in the dopaminergic system (that releases dopamine) because of repeated treatment.

How do SSRI’s treat depression? At first, these chemicals only slightly stimulate serotonin release. Long-term treatment kicks in an adaptive process. The receptor type located on serotonergic neurons which inhibit serotonin activity become insensitive. Repeated treatment frees serotonin neurons from this ‘brake’. By repeatedly using these drugs (with a lag time of 2–8 weeks), the levels of serotonin being transmitted increase and stay high for a longer time which is responsible for the SSRIs antidepressive effect.

The perfect antidepressant could lie in blocking the activity of these receptors since there would be no major delay in action. This hypothesis was confirmed by Francesc Artigas and his research group (University of Barcelona). They administered pindololo, a drug capable of blocking these serotonin receptors, and observed an increase of the antidepressive effect of the drugs paroxetine and fluvoxamine. They worked by reducing the latency period. Patients on pindololo did noticeably better and the clinical data matched that from laboratory animals. Blocking this type of serotonin receptors can be a promising therapy to reduce the latency period and possibly, increase antidepressant action.

My colleagues and I formed an alternative hypothesis as to why the clinical effects of drugs are delayed for so long focusing our attention on the dopaminergic system. We showed that acute administration of different SSRIs reduces the electrical activity of dopaminergic neurons, which release dopamine. These drugs increase the levels of serotonin, which decrease dopaminergic neuronal activity (which release dopamine) by over stimulating another inhibitory serotonin receptor this time located on dopaminergic cells. The result? The drugs taken to cure depression paradoxically initially induce a reduction of dopamine, which is meant to be the neurotransmitter of well-being and happiness! Indeed, SSRIs can worsen the depression of patients in the first few weeks of treatment.

When the drugs are used over a long period of time (3–4 weeks), the initial reduction of dopamine reverses. The change happens because the repeated treatment reduces the sensitivity of this type of serotonin receptor on dopaminergic cells freeing them from their serotonin ‘brake’.

“All of our work has made it possible to consider new treatments of depression”

We think we have found the reason why SSRI antidepressants take so long to work. Two different serotonin receptors need to become insensitive to the level of serotonin in the brain, one found on serotonergic cells, the other on dopaminergic cells. Their insensitivity allows the activity of dopaminergic neurons to return to normal even though the serotonin activity has been bumped up.

Other labs have confirmed our results, which is vital step for a theory to become fact. Cremer and his team (University of Groningen, Netherlands) have shown that blocking the same type of serotonin receptor on dopaminergic cells in rats can improve the effect of SSRIs antidepressants. Ultimately all of our work has made it possible to consider new treatments of depression, which I am very happy to see.

Many questions remain unanswered about depression. The most urgent task is to find a more effective way to treat it. This is my goal, I have spent my life trying to figure out the role of dopamine and serotonin in the brain — with some notable successes. I hope to see the next generation of antidepressants which would improve the life of 121 million depression sufferers.

Ennio listened to me as I expressed my frustration after once again obtaining conflicting results in the laboratory. ‘Giuseppe’ he said ‘You are right, billions of neurons in our brain behave differently, but as Douglas Adams said, ‘If you try and take a cat apart to see how it works, the first thing you have on your hands is a nonworking cat. Life is a level of complexity that almost lies outside our vision’ (Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy). If we want to break the code of the brain and hope to treat its diseases we need to take a holistic approach that takes the whole brain into account.

[ct_divider]

Article dedicated to the prominent researcher Dr Ennio Esposito, Prof. Di Giovanni’s (Department of Physiology and Biochemistry, UoM) colleague and friend. In 2011, he died of a heart attack. During his last years, he suffered from a severe refractory bipolar depression. If interested in an M.Sc. or Ph.D. in biological psychiatry please contact Prof. Giuseppe Di Giovanni

Further Reading

Bortolato M., Pivac N., Muck Seler D., Nikolac Perkovic M., Pessia M., Di Giovanni G., (2013) The role of the serotonergic system at the interface of aggression and suicide. Neuroscience, 236:160-185.

Di Giovanni G., Esposito E. Di Matteo V., (2011). 5-HT2C Receptors in the Pathophysiology of CNS Disease. Springer, New York.

Di Giovanni G., Di Matteo V., Esposito E. (2008) Serotonin-Dopamine Interaction: Experimental and Therapeutic Evidence, Progress in Brain Research, 172. Elsevier, Netherlands.

Depression — The Dana Guide

Depression — National Institute of Mental Health, USA

TED talk about targeted psychiatric medications, similarly to Prof. Digiovanni borne on the realisation that current treatments are not good enough for everyone