What is Malta doing to address this very prevalent problem? Dr Sarah Cuschieri writes about a project called SAĦĦTEK.

In Malta, diabetes has been a health concern since 1886. In 1981, the World Health Organization performed the first national diabetes study in Malta and reported that the total prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is 7.7% (5.9% previously known diabetics and 1.8% newly diagnosed diabetics).

Since then, we have seen that percentage increase through self-reported questionnaire studies such as 2008’s Maltese European Health Interview Survey, which reported a T2DM prevalence of 8.3% in the population aged between 20 and 79. In 2010, it rose again to 10.1%, according to the Maltese European Health Examination Survey. And while this information is definitely useful, it cannot help researchers and doctors investigate what elements contribute to the diabetes epidemic in Malta.

The economic boom over the last four decades has permanently changed the Maltese Islands. With it came a change in lifestyle habits, like car use and diet, and an influx of different cultural and ethnic populations settling on the islands, which meant that it was time to update our understanding of T2DM in Malta; its prevalence, determinants, and risk factors.

I undertook the project “SAĦĦTEK – The University of Malta Health and Wellbeing study” to find out more about T2DM in Malta. SAĦĦTEK was a cross-sectional study that will effectively act like a snapshot in time.

The study population included a randomised sample of adults that had been living in Malta for at least six months and held a permanent Maltese identification card, irrelevant of their country of origin.

How is your health?

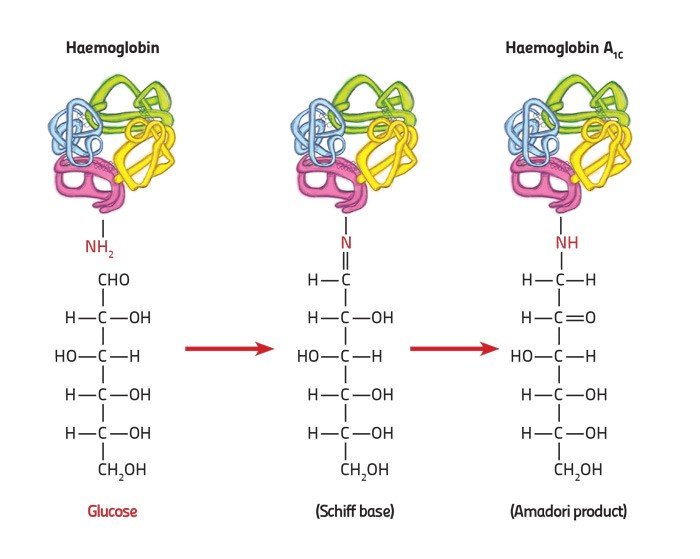

The survey took place between November 2014 and November 2015, and involved 4,000 people (18 to 70 years of age) who were statistically chosen from the national registry. We set up examination hubs in each town where the participants came in to complete socio-demographic questionnaires. While participants were there, we also took several measurements, including blood pressure, weight, height, and waist circumference. Finally, we took blood samples to check for their glucose levels during fasting periods, genetic analysis, and lipid profile (cholesterol and fats in the blood).

In the end, 47.15% of the invited adults actually attended the health survey. From these, we found that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was 10.39%, with males being more affected than females. From the total T2DM group, 6.31% were known diabetics, while the remaining 4.08% were newly diagnosed with T2DM during the study. The numbers mean that over the past couple of decades there has been a rise in the diabetes rate in adults. Higher levels of T2DM mean that related diseases, such as obesity and heart problems, will also be more common.

In fact, study participants were often overweight (35.66%) or obese (34.11%). The weight increase is very relevant because it puts pressure on the body’s organs, including the pancreas, which has a direct link to T2DM development.

An increase in weight increases waist size, and this too comes with its own set of problems called the metabolic syndrome—increased blood pressure being one of many. A third of survey participants reported a high blood pressure (30.12%), again with a male majority.

Tobacco smoking was also prevalent at 24.3% (male majority). Smoking is linked to T2DM development, increased blood pressure, and stroke.

What are the implications?

The survey results are a major public health concern. An unhealthier population means higher demands on Malta’s healthcare services.

In 2016 diabetes cost Malta an estimated €29 million, while obesity cost an estimated €24 million. The increased disease rate identified means that Malta’s bills are set to rise.

Men seem to have a worse health profile than women. Older males with a high body mass index (BMI) were more likely to suffer from high blood pressure. The majority had normal levels of glucose but abnormal lipid profiles, so even though the sugar levels were normal, they were still at risk when it came to acquiring diseases such as heart problems. Those diagnosed with a metabolic syndrome were five-fold more likely to also have T2DM. There is no denying—the gender gap is a concern.

The survey shows that more public health research is in dire demand. Malta’s underlying problem appears to be the increasing overweight-obesity problem. A number of initiatives have already been put in place by the Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Directorate as well as the establishment of “Dar Kenn Għal Saħħtek”, but there is more to be done.

Gender sensitive action is needed. Government, private entities, communities, and NGOs all need to work together to change the harmful lifestyle choices that have become the norm today. Sedentary lifestyles need to change and high intakes of fat, sugar, and salt need to decrease to alleviate Malta’s weight and diabetes problem. A diabetes screening programme also needs to be introduced to help citizens help themselves.

Early diagnosis of this disease will benefit all of Malta’s health and wellbeing and safeguard its health services. What more could we hope for?

Read more:

Cuschieri, S., Vassallo, J., Calleja, N., Pace, N., & Mamo, J. (2016). Diabetes, pre-diabetes and their risk factors in Malta: A study profile of national cross-sectional prevalence study. Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics, 1. https://doi.org/10.1017/gheg.2016.18

Cuschieri, S., Vassallo, J., Calleja, N., et al. (2016). The diabesity health economic crisis-the size of the crisis in a European island state following a cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health; 74: 52.

Cuschieri, S., Vassallo, J., Calleja, N., et al. (2016). Prevalence of obesity in Malta. Obes Sci Pract 2016; 2: 466–470.