When times are hard, frustrated people question why. Conspiracy theories offer attractive answers, sometimes false and sometimes true. Andrew Firbank explores the psychology behind conspiracy theories: Why are they so enticing? What are the risks? And should they be challenged?

Continue readingSafe haven?

Some refer to the Venice Biennale as the pinnacle of the international art world. Last year, feathers were flurried by the Maltese delegation and their representation of Maltese identity. This year, the works question a specific part of the Maltese narrative.

‘We are working around the theme of MALETH,’ says Dr Trevor Borg, artist, curator, and University of Malta lecturer. Maleth refers to the ancient word for Malta. ‘It is also called HAVEN and SAFE PORT.’ These were all terms used in reference to Malta over the centuries. But is our island really that? This is the question being tackled by Borg and his colleagues.

Immigration has been a critical issue in recent years, creating an inflammatory divide in Malta. Borg is using the first immigrants, the animals that travelled to Malta during the ice age, to make his point. ‘They travelled here because of the heat our island provided and the food that came with it. But as the ice in the North started to melt, sea level rose and they were unable to return.’

What is the relation between an (apparent) safe haven and a heterotopia? Here, heterotopia refers to Michel Foucault‘s notion of the ‘other place’. Heterotopias are described as ‘worlds within worlds’, connecting different places. They are places that constitute multiple layers of meaning, that accumulate time, that can be both real and unreal.

To represent this visually, Borg is going to create an archaeological find with hundreds of objects from history. Animal remains will feature, as will unusual artefacts and other strange finds. Borg was inspired by Ghar Dalam and used it as a starting point, but this work is not about history. ‘My work begins at the cave. But I will then leave the cave behind and delve into a distant world that never was! The work responds to fabricated histories, museological conventions, historical interpretations, and hypothetical authenticity. It is based on pseudo-archaeological objects and imaginary narratives,’ he explains.

Collaborating on this work, bringing the artefacts to life is Dr Ing. Emmanuel Francalanza (Faculty of Engineering). The process began at the National History museum in Mdina. ‘Together we selected and scanned a number of animal bones from their archives,’ Francalanza says. This included femurs, teeth, and skulls among others. ‘I then supported Trevor in reconstructing the 3D model and preparing it for printing.’

For Francalanza, this was a chance to apply engineering technologies in new ways, to allow artists to express themselves. But not just. ‘At the same time, this opportunity provides us engineers and scientists with an avenue to explore concepts and even utilise thinking patterns which are not traditionally associated with our disciplines. It helps us be more creative and open to innovative practices.’

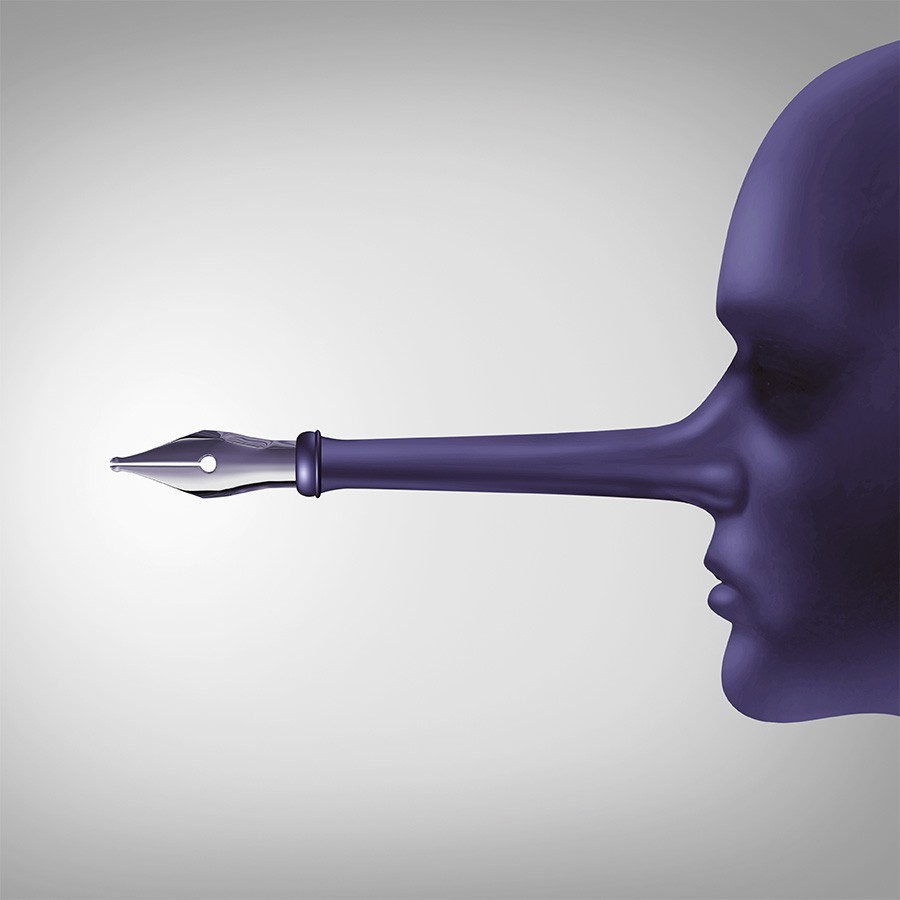

Working together, Borg and Francalanza are blurring the lines between what is real and what is fake. By recreating the original artefacts in such a way that a viewer cannot determine whether what is being seen is authentic, the project is poignant commentary for the post-truth era we are living in.

The great siege of fake information

Information is under siege.