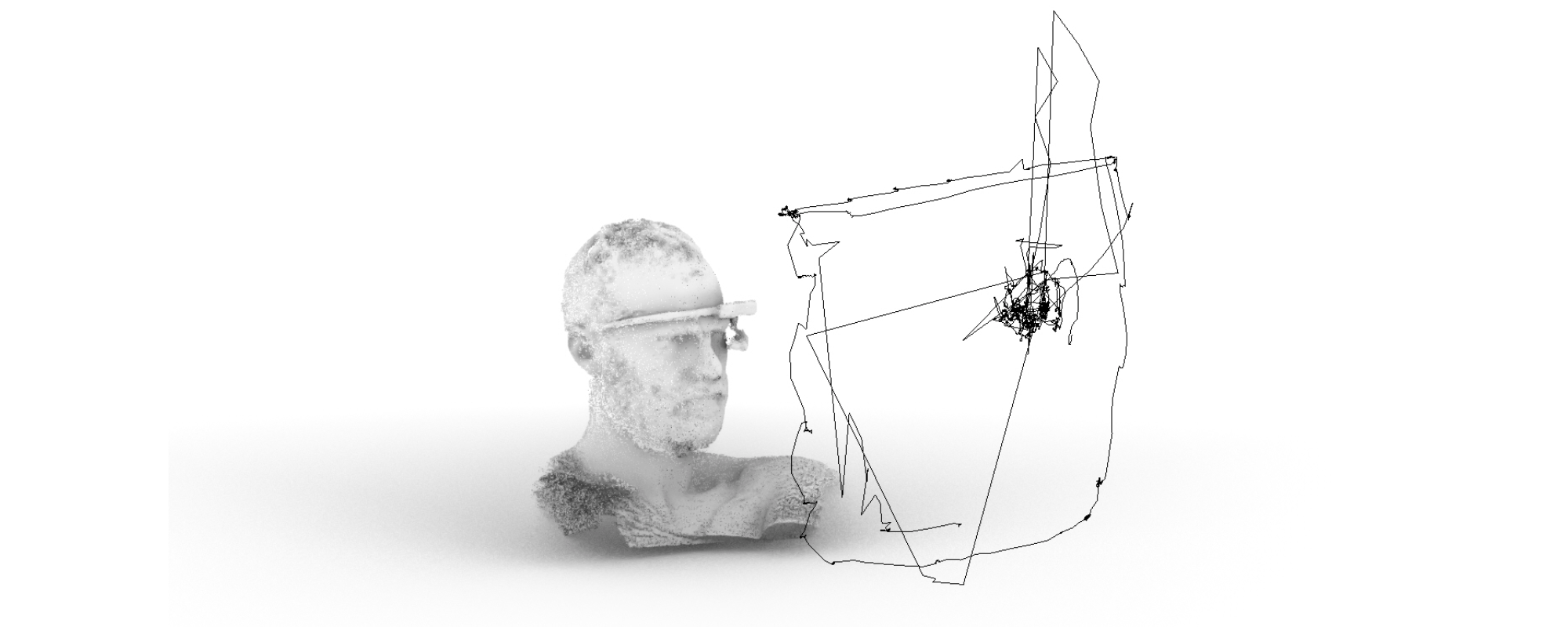

Artist Matthew Attard uses eye-tracking to spark intriguing conversations, challenging us to see the world through new eyes and explore the intersection of art and activism.

Continue readingWhat’s your Face Worth?

While most European citizens remain wary of AI and Facial Recognition, Maltese citizens do not seem to grasp the repercussions of such technology. Artificial Intelligence expert, Prof. Alexiei Dingli (University of Malta), returns to THINK to share his insights.

The camera sweeps across a crowd of people, locates the face of a possible suspect, isolates, and analyses it. Within seconds the police apprehend the suspect through the capricious powers of Facial Recognition technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

A recent survey by the European Union’s agency for fundamental rights revealed how European citizens felt about this technology. Half of the Maltese population would be willing to share their facial image with a public entity, which is surprising given that on average only 17% of Europeans felt comfortable with this practice. Is there a reason for Malta’s disproportionate performance? Artificial Intelligence expert, Prof. Alexiei Dingli (University of Malta), returns to THINK to share his insights.

Facial Recognition uses biometric data to map people’s faces from a photograph or video (biometric data is human characteristics such as fingerprints, gait, voice, and facial patterns). AI is then used to match that data to the right person by comparing it to a database. The technology is now advanced enough to scan a large gathering to identify suspects against police department records.

Data is the new Oil

Facial Recognition and AI have countless uses. They could help prevent crime and find missing persons. They are prepared to unlock your phone, analyse, and influence our consumption habits, even track attendance in schools to ensure children are safe. But shouldn’t there be a limit? Do people really want their faces used by advertisers? Or, by the government to know about your flirtation with an opposing political party? In essence, by giving up this information, will our lives become better?

‘Legislation demands that you are informed,’ points out Dingli. Biometric data can identify you, meaning that it falls under GDPR. People cannot snap pictures of others without their consent; private data cannot be used without permission. Dingli goes on to explain that ‘while shops are using it [Facial Recognition Technology] for security purposes, we have to ask whether this data can lead to further abuses. You should be informed that your data is being collected, why it is being collected, and whether you consent or not. Everyone has a right to privacy.’

Large corporations rely on their audiences’ data. They tailor their ad campaign based on this data to maximise sales. Marketers need this data, from your Facebook interests to tracking cookies on websites. ‘It’s no surprise then,’ laughs Dingli, ‘that Data is the new oil.’

The EU’s survey also found that participants are less inclined to share their data with private companies rather than government entities. Dingli speculates that ‘a government is something which we elect, this tends to give it more credibility than say a private company. The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data breach scandal of 2018 is another possible variable.’

China has embraced Facial Recognition far more than the Western World. Millions of cameras are used to establish an individual citizens’ ‘social score’. If someone litters, their score is reduced. The practise is controversial and raises the issue of errors. Algorithms can mismatch one citizen for another. While an error rate in single digits might not seem like a large margin, even a measly 1% error rate can prove catastrophic for mismatched individuals. A hypothetical 1% error rate in China, with a population of over 1.3 billion, would mean that well over ten million Chinese citizens have been mismatched.

Is privacy necessary?

‘I am convinced that we do not understand our rights,’ Prof. Dingli asserts. ‘We do not really value our privacy and we find it easy to share our data.’ Social media platforms like Facebook made its way into our daily lives without people understanding how it works. The same can be said for AI and facial recognition. It has already seeped its way into our lives, and many of us are already using it—completely unaware. But the question is, how can we guarantee that AI is designed and used responsibly?

Dingli smiles, ‘How can you guarantee that a knife is used responsibly? AI, just like knives, are used by everybody. The problem is that many of us don’t even know we are using AI. We need to educate people. Currently, our knowledge of AI is formed through Hollywood movies. All it takes is a bit more awareness for people to realise that they are using AI right here and now.’

Everyone has a right to privacy and corporations are morally bound to respect that right, individuals are also responsible for the way they treat their own data. A knife, just like data, is a tool. It can be used for both good and evil things. We are responsible for how we use these tools.

To Regulate or Not to Regulate?

Our data might not be tangible, but it is a highly valued commodity. Careless handling of our data, either through cyberattacks or our own inattention, can lead to identity theft. While the technology behind AI and Facial Recognition is highly advanced, it is far from perfect and is still prone to error. The misuse of AI can endanger human rights by manipulating groups of people through the dissemination of disinformation.

Regulating AI is one possibility; it would establish technical standards and could protect consumers, however, this may stifle research. Given that AI is a horizontal field of study, fields such as architecture and medicine must consider the implications of a future with restricted use. An alternative to regulation is the creation of ethical frameworks which would enable researchers to continue expanding AI’s capabilities within moral boundaries. These boundaries would include respecting the rights of participants and drawing a line at research that could be used to cause physical or emotional harm or damage to property.

While the debate regarding regulation rages on, we need to take a closer look at things within our control. While we cannot control where AI and Facial Recognition technology will take us, we can control whom we share our data with. Will we entrust it to an ethical source who will use it to better humanity, or the unscrupulous whose only concern is profit?

Further Reading:

The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data breach involved millions of Facebook users’ data being harvested without their consent by Cambridge Analytica which was later used for political advertising;

Chan, R. (2019). The Cambridge Analytica whistleblower explains how the firm used Facebook data to sway elections. Business Insider. Retrieved 8 July 2020, from https://www.businessinsider.com/cambridge-analytica-whistleblower-christopher-wylie-facebook-data-2019-10.

Malta’s Ethical AI Framework;Parliamentary Secretariat For Financial Services, Digital Economy and Innovation. (2019). Malta Towards Trustworthy AI. Malta’s Ethical AI Framework. Malta.AI. Retrieved 8 July 2020, from https://malta.ai/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Malta_Towards_Ethical_and_Trustworthy_AI_vFINAL.pdf

Blockchain: Not just bitcoin

Blockchain is still a big unknown, even for some professionals. Blockchain and the Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) have been made infamous by Bitcoin, a digital payment and peer-to-peer monetary transaction system that bypasses banks and third party endorsements. But DLT and the Blockchain protocol can be used for other purposes. Blockchain’s greatest strength lies in its decentralised architecture. It allows transactions to be shared openly across independent nodes, verified by encrypted checksums that give each closed block a distinct, indelible signature. All these connected transactions, chained within a common system, make tampering practically impossible. Blockchain is irrevocable, affordable, flexible, and secure.

But what about other applications of these concepts. What if we were to apply such technology to every data exchange? Data and information in the digital age is spearheading the evolution of services and product development, serving a continuum of user demands at all levels and scales, boosting research and innovation applications. Indeed, data is nowadays considered a key ingredient for competitiveness, and this is not about to change anytime soon.

The greatest bottleneck is data sharing. Data production is growing and covering many realms but unfortunately most of it remains locked up in closed databases, enterprises, and institutions. Unofficially it is estimated that the world generates 16 zettabytes of data annually (that’s 16 billion terabyte laptops), but only 1% is analysed. The problem is that data is withheld by data collectors who consider data hoarding to be a right. Where data is released it does not usually flow to users. As a result, we now have institutions running massive centralised databases, often conducting data archaeology, compiling it at local, regional, and global scales. They address the needs of different user groups, but they also impose licensing procedures that ultimately restrain the power of free data flows, establishing unnecessary monopolies.

Blockchain can unleash the full power of data by providing a system for seamless, efficient and secure data transactions. It can lead to so many applications, such as eliminating the need for shipping documents in the transportation of goods, and making the freight and logistics industry more time and cost efficient. Data could be funnelled into artificial intelligence systems to create high performance human-machine interfaces, self-automated robots, cars, and ships. These devices, with information from big data, would be able to learn from their mistakes and autonomously adapt to changing environments. In medicine, large data sets would prove priceless in drug and treatment design, doing away with the constraints of limited sample sizes. The application of such technologies is limited only by our own imagination.

A new digital revolution is looming ahead. Are we ready to be amongst the first to take this leap into the future?