From research-based interventions in New York to a children’s local council in Malta, international minds look for ways to create better urban design to increase residents’ quality of life. Martina Borg and Daiva Repeckaite tune in to hear their thoughts.

Continue readingTourism in Valletta: have we gone too far?

Residents are generally willing to put up with the inconveniences caused by tourism because of its financial and reputational benefits. But is there a tipping point when tourism and leisure become unbearable? Having focused on Valletta as an urban planner, activist, and researcher, Dr John Ebejer warns against the risks of overtourism.

Continue readingCultural Regeneration through Urban Spaces and Places

The effects of a European Capital of Culture are felt through both the cultural activities that take place and through the interactions people have with each other as well as the space around them in their everyday lives.

The Valletta 2018 Foundation has been working tirelessly on several projects preparing Valletta for its title as European Capital of Culture in Malta in 2018. More so, it is researching how these projects are changing the lives of people.

These interactions between communities and their surrounding space are key issues being investigated by the Valletta 2018 Evaluation & Monitoring research process. This is a five-year research study examining the impacts of the European Capital of Culture on Malta’s society and economy.

Dr Antoine Zammit, with the Valletta 2018 Foundation, has been studying the relationship between community inclusion and space in cultural infrastructural projects. His research focuses on four specific infrastructural projects taking place in Valletta as part of the European Capital of Culture: The Valletta Design Cluster (il-Biċċerija) and its surrounding neighbourhood; Strait Street; the relocation of MUŻA – Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti (Malta’s National Museum of Fine Arts) – to Auberge d’Italie and Pjazza de Valette; and the area surrounding the Valletta Covered Market (is-Suq tal-Belt).

The four projects are in different stages of their implementation, and have been dispersed throughout Valletta in a way that allows them to collide with many of the different districts of the capital. While none lack cultural significance, each project has displayed different strengths in implementation. The Valletta Market and Strait Street Projects have a particularly strong commercial value, while the Valletta Design Cluster is aimed at creative design and encouraging entreprenuership. MUŻA, more overtly than any of the other three projects, is an attempt at traditional forms of cultural engagement and regeneration through the development of a national, community-driven musuem of art. Zammit, together with two M.Arch. (Architecture and Urban Design) students—Daniel Attard and Christopher Azzopardi—carried out extensive studies to gain a deeper understanding of the sites.

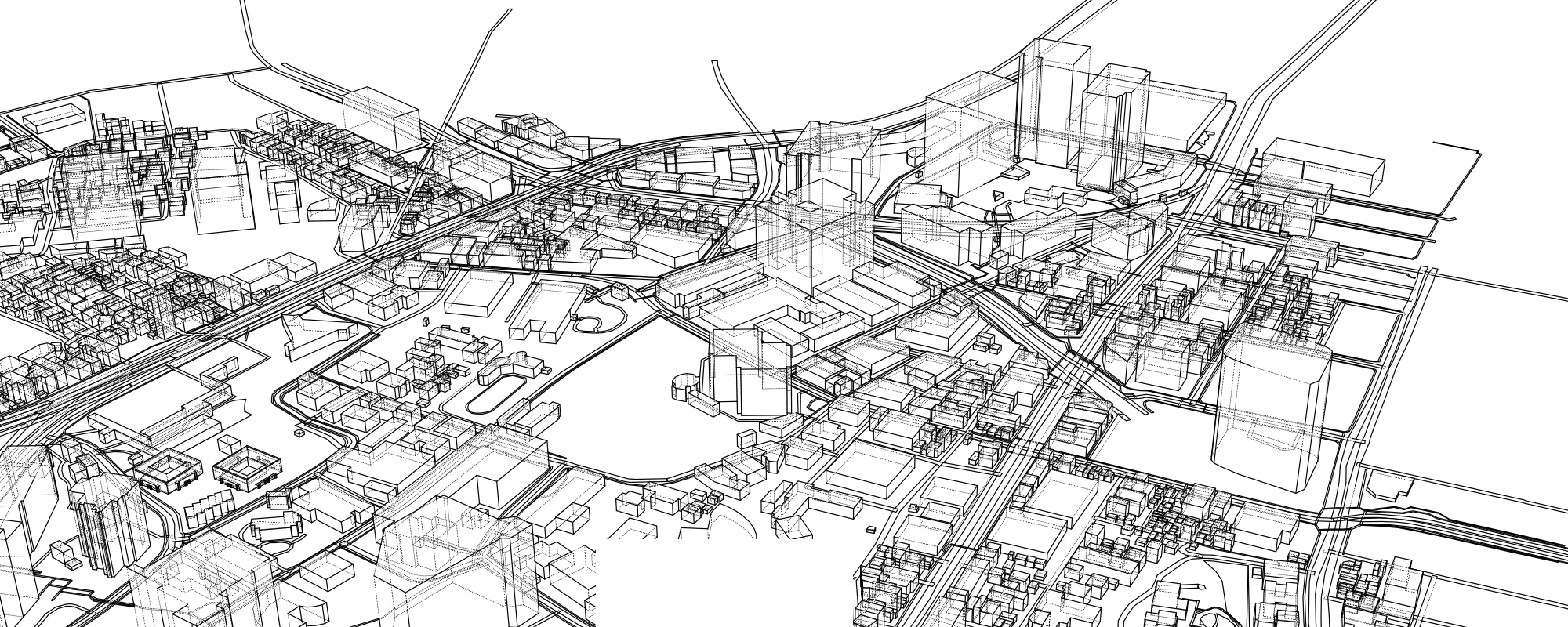

“Quality urban design has increasingly become about creating these habitable places. It is ultimately all about the quality of life of residents.”

Attard developed a matrix in order to score the different types of interactions within each site. Split into categories such as ‘aural’, ‘user categories’ and ‘actual use of space,’ the sections help identify emerging patterns and traits from the implementations of the projects. The Biċċerija and Strait Street all score high in the ‘aural’ category, meaning various elements that contributed to noise, or the lack of it, were observed. MUŻA and the Covered Market both qualified for the ‘user categories’ section, meaning that a relatively diverse demographic was observed making use of the place. The Valletta Design Cluster was noted for having a higher level of human interaction take place daily (balcony conversations, loud conversations in general, and so on). Finally, all four sites qualified for the category of ‘actual use of space,’ meaning that people actively show awareness of the space by taking photos, complaining due to lack of public conveniences, construction work, and shops setting up or closing down, among other things.

On the other hand, Azzopardi focused on the spatial quality of the sites by looking at their accessibility and permeability, perception and comfort, and the vitality of the four sites. Of the four, Strait Street, more specifically the intersection with Old Theatre Street, scored highest, followed by MUŻA and the Valletta Market. The Valletta Design Cluster obtained the lowest score, suggesting that the site in its current state is poorly perceived and somewhat inaccessible. Matching Azzopardi’s findings with statistical data, obtained at a neighbourhood level through the NSO’s evaluation of the available 2011 Census Data, Zammit has determined some relationship (but not statistically significant), between the buildings’ current state of repair and the community’s achievements in literacy, education, and employment.

| Museum of the People |

|

Naqsam il-MUŻA is a branch project inspired by MUŻA. Currently in progress, participants in the Naqsam il-MUŻA project were selected from different communities around Malta and taken to see the art collection of the National Museum of Fine Arts. They will then exhibit their choice of artwork from the museum in their localities. It brings the museum to the people, rather than the other way round. |

The diversity of the four sites were key to Zammit’s studies. He studied the effect their differing cultural infrastructure had on the cultural regeneration of Valletta. ‘Cultural infrastructure entails those interventions, which generally have some kind of physical implication, in an urban space which tends to enhance and broaden people’s cultural appreciation,’ explains Dr Zammit, ‘but I see it as requiring an added value. In my opinion, art for art’s sake in these cases doesn’t mean anything. Which is why the question which I try to answer in my research is, “what will that infrastructure give back to the community at the end of it all?”’ Other research, similar to Zammit’s, holds that more than just creating spaces, cultural regenerative projects should aim to create places which result from quality urban design. ‘Over the past two years, I started to realise that the real difference is ‘between places that are alive, versus habitable places,’ comments Zammit, who thinks that, ‘quality urban design has increasingly become about creating these habitable places. It is ultimately all about the quality of life of residents.’ This issue of liveability is key to being a European Capital of Culture. Its goals are to create high-quality cultural and artistic activities while improving the quality of life of communities through culture. Zammit’s study highlights many potential issues such as an increase in noise pollution, gentrification resulting from a rise in property values and rental prices, and other potential impacts on Valletta residents. The Valletta 2018 Foundation is discussing these issues in its upcoming conference Cities as Community Spaces in November 2016, which will bring together a number of international speakers to explore how different communities make use of public spaces for creativity, contestation, and interaction.

For more: valletta2018.org