Residents are generally willing to put up with the inconveniences caused by tourism because of its financial and reputational benefits. But is there a tipping point when tourism and leisure become unbearable? Having focused on Valletta as an urban planner, activist, and researcher, Dr John Ebejer warns against the risks of overtourism.

Valletta was always a subject of public debate. In the 1990s, it was bleeding residents, undergoing a takeover by offices, deadlocked traffic, vacant properties, and deteriorating structures. During the day, it was full of life with shoppers, office workers, and residents, but it was far too quiet after sunset, turning into a ghost town. Today, Valletta’s issues are different. Valletta has become tourists’ Instagram darling – but is it becoming unliveable?

Let us zoom out a little. My involvement with Valletta started in the mid-1990s when I was working on local plans at the Planning Authority. Before the year 2000, public investment in urban conservation was limited to minor restoration, with noteworthy projects being few and far between. Moreover, scarce investment in private properties created a gradual, downward spiral and increased dilapidation.

After the year 2000, authorities consolidated their efforts to bring about positive change in our capital city. They extended pedestrian areas to encompass the main spaces of St George’s Square, Merchants Street, Castille Square, and Triton Fountain. Moreover, the City Gate project, by renowned architect Renzo Piano, provided new pedestrian spaces at Valletta’s entrance. Before 2005, I distinctly remember instances of tourist groups crowding onto narrow pavements on Merchants Street, blocking other pedestrians, while listening to their guide. Doing away with car traffic created pleasant spaces, allowing visitors to better appreciate Valletta’s urban heritage.

To be successful, pedestrianisation needs a holistic transport strategy. Vehicle access was controlled through an automatic payment system for all non-residents parking in Valletta, coupled with a park and ride system, as well as extensive parking outside Valletta. Bus terminus facilities got a facelift, and a passenger lift connected the waterfront to the city centre.

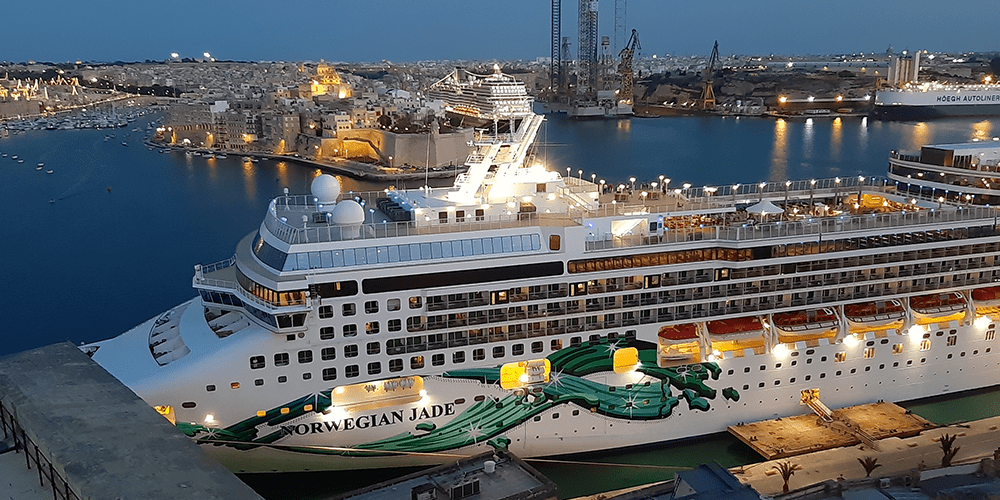

The government invested heavily in Valletta. The most notable was the City Gate project with the new parliament building, an open air performance space and a new entrance to the city. Other important projects were the Centre for Creativity (Spazju Kreattiv), Valletta Cruise Passenger Terminal, Fort St Elmo, the Fortifications Interpretation Centre, extensive restorations of fortifications, MUŻew Nazzjonali tal-Arti (MUŻA), and the Old Valletta Market. Coupled together, they gave Valletta the facelift it needed.

Three primary motives drove major public investment in Valletta. Firstly, Valletta is a World Heritage Site and includes a concentration of historic buildings and monuments. This imposes a moral obligation upon the authorities and society to take good care of our urban heritage. Secondly, these investments aimed to make Valletta attractive for people to live and work. Thirdly, Malta’s tourism policy shifted to attract cultural tourists, while retaining its market share as a sun and sea destination.

Public investments gave people added confidence to invest in Valletta properties, either for private residential or for commercial use. When Valletta was designated as a European Capital of Culture for 2018, private investors realised the opportunities that a revitalised Valletta offered. Many historic private properties were reborn as high-end residences, boutique hotels, short-term tourist rentals, and catering establishments.

Tourism is typically considered to benefit host communities because it generates income and employment. But when the level of intrusion and inconvenience becomes excessive, like in Venice, Barcelona, and Amsterdam, it becomes overtourism. The impacts from overtourism are overcrowding in the city’s public spaces, traffic congestion, excessive touristification, inappropriate visitor behaviour, and displacement of long-term residents.

Global changes in the tourism industry impacted the dynamics of Malta’s tourism sector. In 2006, Malta opened up to low cost airlines. Independent online booking made travelling easier and cheaper, resulting in a more diversified and less seasonal industry. For Malta, that meant moving away from dependence on tour operators. In 2006, two of every three tourists used tour operators. Today that figure hovers around one in three. With increased seat capacity and the ease of independent travel, the number of arrivals ballooned from 1.2 million in 2006 to around 2.6 million in 2019. Of course, more tourists to Malta signifies more visitors in Valletta.

The demand for boutique hotels and short-term rental accommodation has pushed property prices up. People with family roots in the City are moving out, replaced in part by new and somewhat detached residents. Ongoing gentrification is a process of change that may result in the loss of community-based social and cultural activities. On the other hand, new residents bring cultural diversity and much needed investment into the capital. Properties which would otherwise decay are restored and brought back into use.

Increased tourism activity has reduced Valletta’s liveability in many ways. Over the last two decades, more bars and restaurants have opened and extended their working hours. Many catering establishments have sprawled onto the streets, placing tables and chairs outside their premises. Their pleasant ambience for diners and passers-by is a source of noise and nuisance to residents in the immediate vicinity, more so in the summer when locals leave their windows open. Apart from noise, external tables and chairs also have aesthetic implications. The canopies and umbrellas that go with them are often visually intrusive and undermine the aesthetics of the historic environment. In some streets, tables and chairs impede the flow of pedestrians, resulting in crowding. Weak enforcement exacerbates the problems.

On top of this, building alterations and additions are compromising the value and integrity of historic buildings. The Valletta Local Council, supported by three environmental NGOs, appealed for urgent action to safeguard the city. In a joint press conference on 28 January 2017, they expressed concern that Valletta was undergoing ‘an unprecedented barrage of new developments, many of which are not sensitive to the values and fragile nature of the historic setting’. They argued that ‘the intensification in activity is giving rise to new threats to the liveability of the city and to the safeguarding of its Outstanding Universal Value, which is the basis of its World Heritage Status.’

Valletta is home to a resident community with a strong social and cultural life. Living in Valletta has always been subject to some inconveniences, but these have increased in recent years. This is problematic as it will further deplete Valletta’s resident community, which lost one in seven residents over 10 years and currently stands at around six thousand.

Current tourism impacts on Valletta are manageable, but the trends are very worrying, not least because the authorities seem focused on pushing forward the commercialisation of Valletta without considering the detrimental effects on residents. Unless corrective action is taken, twenty years down the line we may be facing the worst case scenario of a Valletta with parishes that can no longer function for lack of residents. We could end up with Valletta’s piazzas and streets becoming open-air restaurants, with little or no space for pedestrians. Valletta may become a leading centre for Malta’s night-time entertainment, but this would be a departure from its cultural and heritage vocation.

To manage unwanted impacts, relevant public authorities must genuinely consult with Valletta residents and other stakeholders. Together, they need to find balance in safeguarding the liveability of Valletta while tapping its tourism and heritage potential.

What do you THINK? What future lies ahead for Valletta? What needs to be done for a better Valletta? Post your comments online on THINK or write to me on john.ebejer@um.edu.mt.

Further reading:

Ebejer, J. (2016) Regenerating Valletta: a vision for Valletta beyond 2020. In Ebejer, J. (ed.), Proceedings of Valletta Alive Foundation Seminar: Valletta Beyond 2020, 35–44.

Ebejer, J. (2019) Urban heritage and cultural tourism development: a case study of Valletta’s role in Malta’s tourism. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 17(3), 306–320, DOI:10.1080/14766825.2018.1447950.

Ebejer, J.; Smith, A.; Stevenson, N. & Maitland, R. (2019) The tourist experience of heritage urban spaces: Valletta as a case study. Tourism Planning & Development. DOI:10.1080/21568316.2019.1683886.

Comments are closed for this article!