How do you help school children handle fights, bullying, and other conflict properly? You build a game, of course, and you let children take on different roles in a village. But how does that lead to resolving conflicts? Ashley Davis met researchers Prof. Rilla Khaled and Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis to find out more

Do you chuckle at the thought of a serious game? The phrase is an oxymoron. How can a game be serious? Games are meant to be fun, frivolous, a way to pass the time. Or else you sometimes hear that games are anything but frivolous. That video game violence in particular is a threat to social order. The idea that games can be used to advance human understanding about the world, and that they can help us to teach, train, or motivate people in some way, is something that still needs to enter our mentality.

Designing games to explore research questions and to solve real world problems is actually a very important aspect of games research, an area of applied research that now has a strong presence at the University of Malta with the establishment of the Institute of Digital Games. Researchers from the Institute work on European-funded projects to create games that tackle serious problems affecting children and adults alike.

Village Voices has been voted the best learning game in Europe at the 2013 Serious Game Awards

Prof. Rilla Khaled and Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis are two researchers now based at the Institute of Digital Games who work on serious game projects. Khaled’s work focuses on serious game design, while Yannakakis is a specialist in artificial intelligence and computational creativity. Computational creativity tries to build upon the latest technological innovations in human–computer interaction that enable computers to act intelligently to some aspects of human beings. These two areas, game design and game technology, represent a large part of the teaching and research strengths of the Institute.

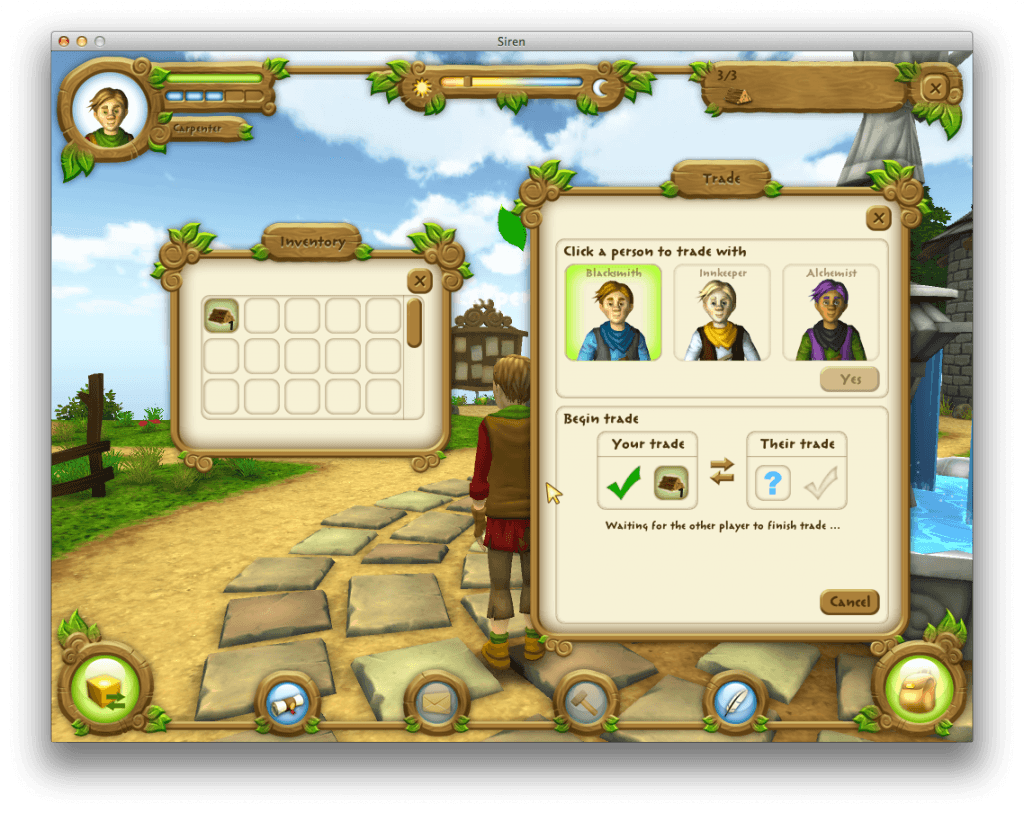

One game that Khaled and Yannakakis recently helped develop is Village Voices which has been voted the best learning game in Europe at the 2013 Serious Game Awards. It was developed as part of the SIREN project, an FP7-funded interdisciplinary consortium made up of researchers from Malta, Greece, Denmark, Portugal, the UK and the US, along with Serious Games Interactive, a Danish Games Studio.

Let’s take a look at what makes a serious game and think about what made the project a success and what didn’t work so well.

The serious side of Village Voices aims to help school children learn conflict resolution skills. Players take on the role of one of four interdependent villages that are situated in a farm setting and given various quests to complete. Sitting side-by-side at separate computers, they may collaborate, share resources and help each other, or they may spread rumours and steal from each other. Much like any playground setting, children can play nicely, or they can be bullies.

The purpose of the SIREN project was to apply the latest advancements in game technology to the creation of serious games. The brief focused on innovations in procedural content generation, an area of artificial intelligence that automatically builds game elements like game levels or quest structures that would otherwise need to be designed manually. Another part of this innovative technology is detecting the emotions of players. Physiological responses can be measure through various tech like Electroencephalographic (EEG) sensors that can be used to detect a person’s emotional state directly by reading their brain’s electrical signals. Virtual agents were another technology that interested the research team. These agents are believable non-player characters that interact with the player with perceived intelligence.

The idea was to then create a game that would adapt to player behaviour, using emotion recognition tools to create an individual experience for each player. The decision to focus the game on teaching children about conflict resolution came later. Rather than to create a game about bullying behaviour, which is what a lot of people think of when they picture conflict between children, the research team wanted to explore the kinds of everyday conflicts that take place in school-yards. Friendship disputes, differences in opinion, and arguments over the possession of classroom items might seem trivial to adults, but they are important problems for children for whom school is their entire world. The SIREN consortium envisioned a game where players could experience and resolve conflicts in a dynamic setting.

Some people who make serious games say that the serious application of the game should take precedence over fun. They say that serious games should offer players a safe environment to try out new behaviours. Khaled disagreed with this approach to game design. ‘Serious game experiences need to feel real and not trivial. Otherwise why would we then use them to raise a mirror to reality?’

Village Voices allows actions that teachers might find surprising. Players can be destructive in that world. They can steal from each other. The game gives aggressive players a noose with which to hang themselves. Knowing that the person whose labours you just destroyed, or who stole the items you were collecting, is sitting right there next to you intensifies the game’s emotional experience. Exchanges can become heated between players. It is these kinds of heated exchanges that often makes games fun.

Games are usually poor at provoking emotional responses. Village Voices does exactly that. Khaled told me about one session in a British classroom (the game was tested across Europe). A female student had such an upsetting experience that she cried. After reflecting on the incident with her teacher, the researcher, and the other players, the girl later returned to play again. Khaled thought this was a breakthrough learning moment for the student.

So Village Voices is a good learning tool, and it is also fun to play. But how successful was the team in applying game technologies like procedural content generation and emotion detection to its design? Khaled said that the experience of designing a game primarily for the purpose of testing technological innovations was the hardest part of the project. You might think that the role of a game designer is to work out the best solution to a problem given the technologies at hand. However, when the application of technology is the problem, the relationship between design and technology is more complex. Khaled said that the need to include particular game technologies in the design of Village Voices created a situation much like a rock band that needs to accommodate a peripheral member, such as a violin player. ‘While the violin player is not core to the project, the whole project needs to be compromised in some way in order to show off the violin player’s skills. It is not clear that the violinist is going to help the band make a new hit song, but it is clear he has to be there. So the band tries to find the violin player’s most positive qualities because he has got to be there.’

In Village Voices, the violin player’s best qualities are adaptive technologies that make the player experience more personalised. Because support for emotion detection plug-ins was never actually included in the final prototype, the game instead asks players directly how they feel about events in the game and introduces variations to the player experience according to their responses.

So far we have seen that Village Voices was successful according to the popular opinion of game-design peers at the European Serious Games — it won an award. We have also seen anecdotally that it is a provocative, if not fun game, based on the British student’s emotional response. But what does the SIREN team think about the game?

You cannot sit a child down in front of a computer and hope that they will magically learn something

According to Khaled, it can be difficult to implement learning games in classroom settings, and even more difficult to properly evaluate them. Project funding usually runs dry after around three years, and games take most of that time to develop. Gaining access to schools is also difficult. The game is a good fit for classes like social studies that are often held only once or twice a week. Together with the problem of semester breaks and short evaluation periods, as well as the tendency for teachers to have access to only a few computers often equipped with obsolete hardware, researchers would rarely see students engage with Village Voices over a long period of time. All these things place limitations on the design, testing, and evaluation of games for research purposes.

Rigorous evaluation is important as, ultimately, learning games are not black box tools. You cannot sit a child down in front of a computer and hope that they will magically learn something. That vital learning moment comes when players discuss their in-game experiences. As Khaled explained, ‘Playing the game is just half the experience. The other half is the subsequent discussion of the game experience.’

Given that discussion is so essential to the evaluation process, and that it is so difficult to get a sample of those discussions in a research setting, I asked Khaled if it was possible to turn the discussion into a game as well, to include it as part of the package. Khaled mentioned the meta-game, the part of the game where a player is both playing and watching themselves play the game. It is in the meta-game that players achieve the highest level of reflection. It works well as a kind of after-game discussion, a debriefing for players as they leave behind the conflicts of the game world and return to the everyday life of the school-yard; but Khaled added that of course it could be turned into a game. Achieving this level of reflection in the game package itself is just another challenge for the designers of serious games.

The Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta offers world-class postgraduate education and research in game studies, design, and technology. The inter-disciplinary team includes researchers from literature and media studies, design, computer science and human-computer interaction. Visit game.edu.mt or contact Ashley Davis (ashley.davis@um.edu.mt) for information about the Institute’s Master of Science (taught or by research) and Ph.D. programmes. This article forms part of The Gaming Issue.

Find out more:

-

Cheong, Y-G., Khaled, R., Yannakakis, G., Campos, J., Paiva, A., Martinho, C., Ingram, G. A Computational Approach Towards Conflict Resolution for Serious Games (full paper). In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games, 2011.

-

Khaled, R. and Ingram, G. Tales from the Front Lines of a Large-Scale Serious Game Project (full paper). In the Proceedings of CHI ’12, 2012.

-

Vasalou, A. and Khaled, R. Designing from the Sidelines: Design in a Technology-Centered Serious Game Project. In the Proceedings of the CHI Workshop Let’s talk about Failures: Why was the Game for Children not a Success? CHI ’13, 2013.