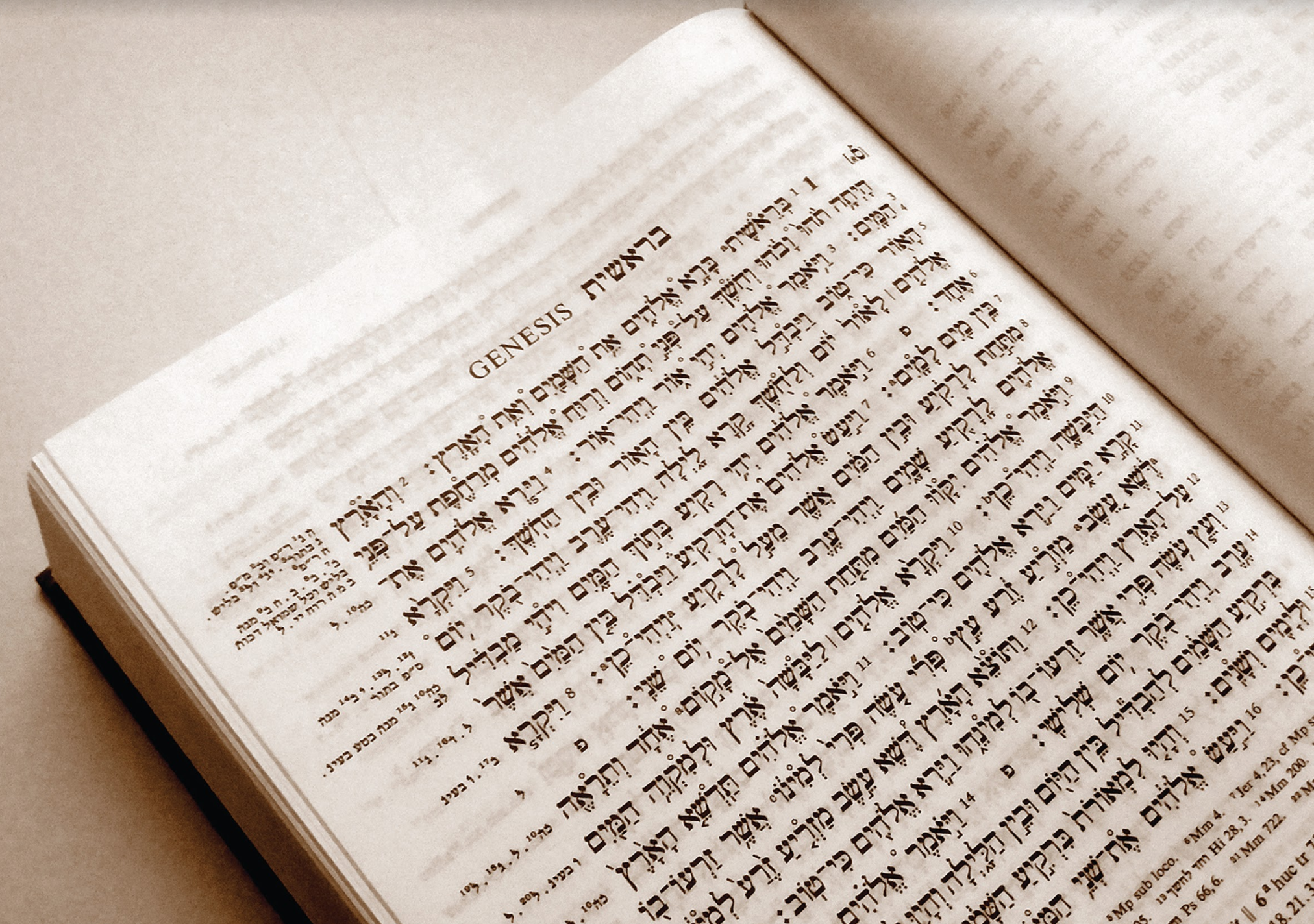

Classical Hebrew is the Hebrew of the Tanakh, the Jewish Scriptures, the very source of the Christian Old Testament. Its first appearance in the historical record dates back to the 10th century BCE, and like the other semitic languages from which it emerged, it was written from right to left and comprises only consonants. By the turn of the Common or Current Era, its use as a spoken language was quickly being superseded by Aramaic and Greek. A few centuries later it was a linguistic relic, its use limited to liturgical and literary contexts, not so different from the use of Latin much later in the Christian west.

‘Dead’ languages bring up the question of relevance. They are limited in their vocabulary, especially when compared to their contemporaries; the Classical Hebrew lexicon amounts to just about 10,000 words. Today, they could not be used for communication, on official documents, or for most conventional things. However, there is one function ancient languages fulfill in a far superior manner—interpreting ancient texts.

Modern translations cannot quite capture the nuance of ancient texts. Translators can only convey ideas after making countless choices in the understanding and rendering of words, all while being consciously or unconsciously guided by their own ideological leanings. Translations are essentially interpretative exercises. Armed with knowledge of the original language, a reader can identify the original authors’ ideology, emphasis, word order, and tone. All of these features could easily be lost in translation. For example, should the word ‘meshihu’ in Psalm 2:2 be translated as ‘his Messiah’ or ‘his Christ’ or ‘his Anointed One’? A choice needs to be made, and that choice does make a difference.

Archaeologists use the same concept when studying ancient artefacts, as do epigraphists, the specialists who study inscriptions. Understanding the inscribed language on items leads to a clearer, more colourful picture of its context and origins. The Malta Government Scholarship Scheme supported me in carrying out such an epigraphic study for my doctoral research at the University of Oxford. My project dealt specifically with a group of inscribed pottery sherds discovered at Lachish (modern Tell ed-Duweir) in Israel. Combined with an archaeological and contextual reassessment, these inscriptions provided valuable insight into the socio-political history of early 6th-century BCE Judah, including scribal culture and the mastery of the contemporary Hebrew language, as well as military operations and prophetic activity, all of which strike similarities with the Book of Jeremiah.

Studying Classical Hebrew can be a rigorous mental workout that instills an appreciation for detail: an insight useful across innumerable fields. Not only does it provide a solid foundation for Modern Hebrew, but it offers a fresh perspective for those wishing to read biblical texts in a critical manner. After all, the Bible remains an iconic cultural artefact in the western world, vital when discussing not only ideology but even cinema, literature, music, and art.

Ancient languages give a voice to our history and the people who shaped it, all the while providing food for thought for those in the present.

For more information: The Department of Oriental Studies (Faculty of Arts, University of Malta) offers study-units on Classical Hebrew grammar, syntax, and readings at undergraduate level.