Women are often objectified and sexualised in popular culture, while other, non-binary genders are hardly represented at all. Three students from the Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) use their art to explore and better understand this issue.

Gender in Branding

Gender is a social construct. It is the result of decades worth of misogyny, stereotyping, and inequality. Yet if society determines what is masculine, feminine, and everything in between, then society can also change it. There is a long way to go, but Alessia Cacciatore, Francesca Vella, and Michael Stilon are taking the first step to recognise what these outdated inequalities are.

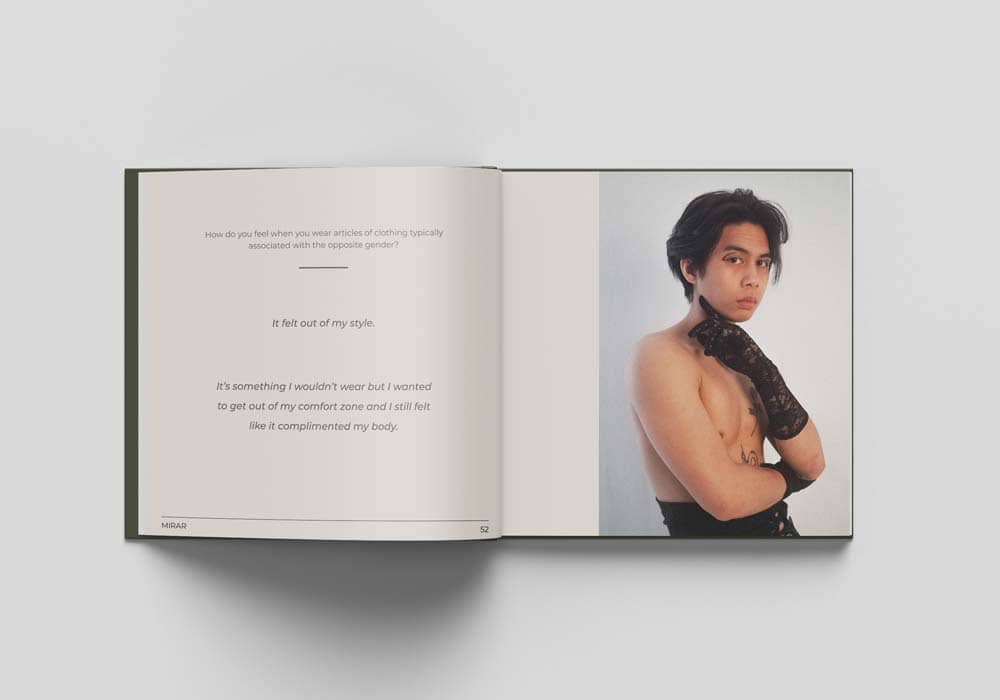

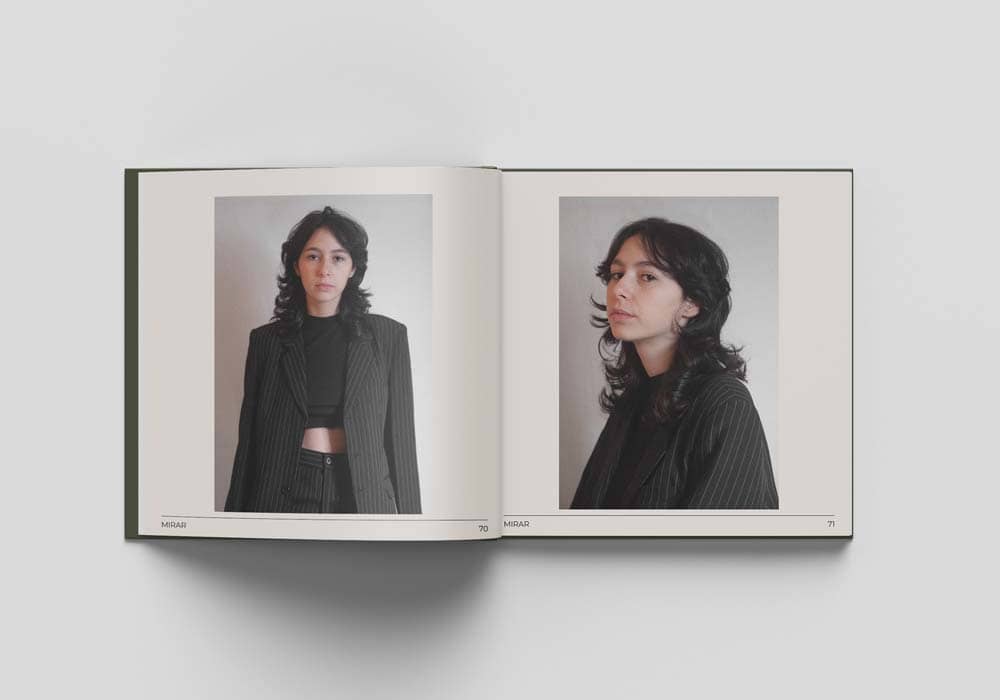

Alessia Cacciatore – MIRAR

Our appearance is one of the first things people notice: in particular, the clothes we wear. The right outfit can fill us with confidence for an interview or a night out partying. It is also a way of expressing ourselves. Yet, most fashion brands limit themselves to binary genders. Alessia’s art investigates the western cultural constructs of feminity and masculinity behind clothing.

‘Prior to the 18th century, silhouettes between men and women were quite similar,’ Alessia explains. ‘When men started working more physical labour, comfort took over style. They started wearing pants, for example. For women, it was only during WWI that they started wearing pants as they began to work men’s jobs. This died down after the war ended, only to resurface with WWII. Around the 1960s, men started wearing feminised clothes as an act of rebellion. Superstars such as David Bowie and Kurt Cobain eventually paved the way for unisex or androgynous fashion. That’s when gender fluidity really started.’

Alessia’s work attempts to reconstruct fluidity in order to blur the fashion rules between males and females. This involved models wearing clothes that weren’t designed for their particular gender. She explains how ‘the biggest part of the project was seeing how the models reacted.’ The female models expressed how they felt comfortable and empowered while wearing clothes designed for men. Of particular note is how the models said that ‘I don’t have to act feminine, I can act like myself,’ highlighting a troubling note for the way feminine fashion is viewed. The male models had differing opinions. One of the male models explained how he was uncomfortable wearing clothes designed for women. The other model felt really comfortable, saying, ‘if I weren’t in Malta, I would wear this on a regular basis.’

Alessia mentions that women are more used to wearing men’s fashion while for men, wearing women’s clothes is something you can’t really do. This could help explain the models’ reactions. ‘It’s what we teach each other, and not what nature teaches us.’ According to Alessia, gender constructs can and do determine fashion. ‘When you’re wearing your regular clothes, you’re only wearing those things because you were taught so from a young age. This was further reinforced by your parents and society.’

Michael Stilon – Challenging Female Gender Stereotypes through Games

Our upbringing, peers, society, and the media all contribute to stereotypes. Micheal Stilon explores games and specifically how female gender stereotypes are portrayed. To do so, he created a card game based on the game Snap. The focus isn’t on the gameplay aspect, but rather on the way the figures on the cards are depicted. ‘I wanted to go with something that doesn’t show you straight in your face what the motif behind it is.’

At first glance, only a handful of the symbols appear familiar. Athena, symbolised as an owl, might ring a bell to some, but Michael also utilises less familiar icons such as Durga the Hindu deity of motherhood and the native American Spider Grandmother. Michael admits, ‘Avoiding generic designs was tricky. Originally it wasn’t going to be symbols, it was more character design. But the symbols made more sense as they have a deeper meaning and history to draw from.’ The cards are mostly inspired by mythology. Michael goes on to explain that while each card symbolises something different, they all lead to female characteristics. ‘Most people would probably play the game for the first time and not notice. But eventually, after multiple games, the cards might inspire them to take an interest and look into it.’

One of the biggest challenges for Michael was designing something with no experience as a victim of the issues analysed. ‘I listened, really listened, to every single person and their experiences. Going through websites where people told their stories. I tried to put myself in their shoes.’

Michael is hopeful that games can change our perspective on gender. After all, ‘if games are able to negatively impact the way we think, then they can also positively affect the way we think. Although it might be harder, I do believe it is still possible.’ While there has been some progress in recent years, particularly with younger generations, there is still a lot that needs to be done to challenge and address gender stereotypes.

Francesca Vella – Blare

Branding represents a company, its values, and its mission. Unless carefully planned, a branding exercise can quickly backfire, as Dove quickly learned in 2017. Brands continue using outdated techniques and gender stereotypes, alienating members of their audience. According to Francesca Vella, these types of branding exercises only serve to reinforce toxic stereotypes.

‘Unfortunately, when it comes to certain products and courses, a lot of things are associated with one gender over the other.’ Francesca created a set of brand guidelines for a fictitious brand named BLARE, an NGO that promotes equality in educational institutions and practices what it preaches. ‘My dissertation hints at the fact that branding and marketing campaigns could be a reason that contributes to gender gaps in STEM courses. I wanted to tackle the education gap faced by designers who keep implementing these stereotypes within their branding.’

Some of the main gender stereotypes used include typography, colours, and tone of voice. ‘For example, women tend to be seen as more dainty which is reflected in cursive typography, while for products aimed at men, stronger and bolder typography is used.’ For her brand guidelines, Francesca disregarded the idea of targeting one gender over the other just to bridge a gap. ‘I’m presenting a long-term solution, rather than trying to bridge a gap that in reality, could end up creating a new gap.’

Similar to other artists, Francesca points out that changing gender stereotypes in branding is a long process. ‘I really recommend studying the audience you’re trying to reach. But this target audience shouldn’t be based on gender. We live in a fluid society, so in the end, limiting yourself to a gender is going to limit your audience. Study your audience and make sure you don’t reinforce these stereotypes.’

These three students have taken the first step to dismantle gender stereotypes. They form part of an entire exhibition among their Bachelor of Fine Arts class. The exhibition was held on the 20th and 21st of May on the fourth floor of the Faculty of Media and Knowledge Sciences building on Campus.

Comments are closed for this article!