In cities, pollution remains a pressing environmental concern for pedestrians. THINK sits down with Prof. Ing. Daniel Micallef and Dr Edward Duca from UM, who are using plants and physical barriers to combat traffic-generated pollution.

With over half the world’s population living in cities, these hubs emit large amounts of pollutants. Traffic is the main culprit of this pollution, and people walking around these cities bear the brunt of it, lowering their quality of life, health and lifespan. To try to solve these issues, UM researchers launched the APACHE project to use nature to help protect pedestrians, using a Maltese town as a test bed.

The APACHE project, led by Prof. Ing. Daniel Micallef and Dr Edward Duca, aims to reduce fine dust particles in the air. Micallef (Head of the Department of Environmental Design) has always been active in developing forward-looking research projects and funding applications. The APACHE project is his latest challenge to build a more sustainable future in Malta, with the support of researchers Jeremy Sacco and Sudarshan Ramesh. Duca (Rector’s Delegate for STEM Popularisation) joined forces as a project partner, contributing by planning impact assessments, citizen feedback on research design, and organising TV appearances and public talks.

First conceived by Micallef, the project is concerned with the impact of wind in the built environment. This facilitated the coming together of education and science, which is vital for finding effective solutions that have proven to mitigate issues such as those in the Rue D’Argens case study in Gzira.

Air Quality Control: A Novel Approach to Enhancing Health

Inspired by UM researchers’ involvement in VARCITIES and JUSTNature (two H2020 EU-funded projects), the ‘Aerodynamic, Pedestrian Level, Air-quality Control using Urban Vegetation Elements’ Project (APACHE) looks at how nature-based solutions can lead to healthier, low-carbon cities. ‘The concept was to erect barriers between cars and people,’ explains Duca, emphasising the importance of safeguarding the health and well-being of vulnerable groups. Duca continues, ‘This is crucial as pollutant dispersal often remains at ground level.’ Micallef adds, ‘While pollutant concentration may be prevalent across various areas, the project adopts a pioneering approach to limit pollutants in street zones by mitigating air pollution dispersion.’

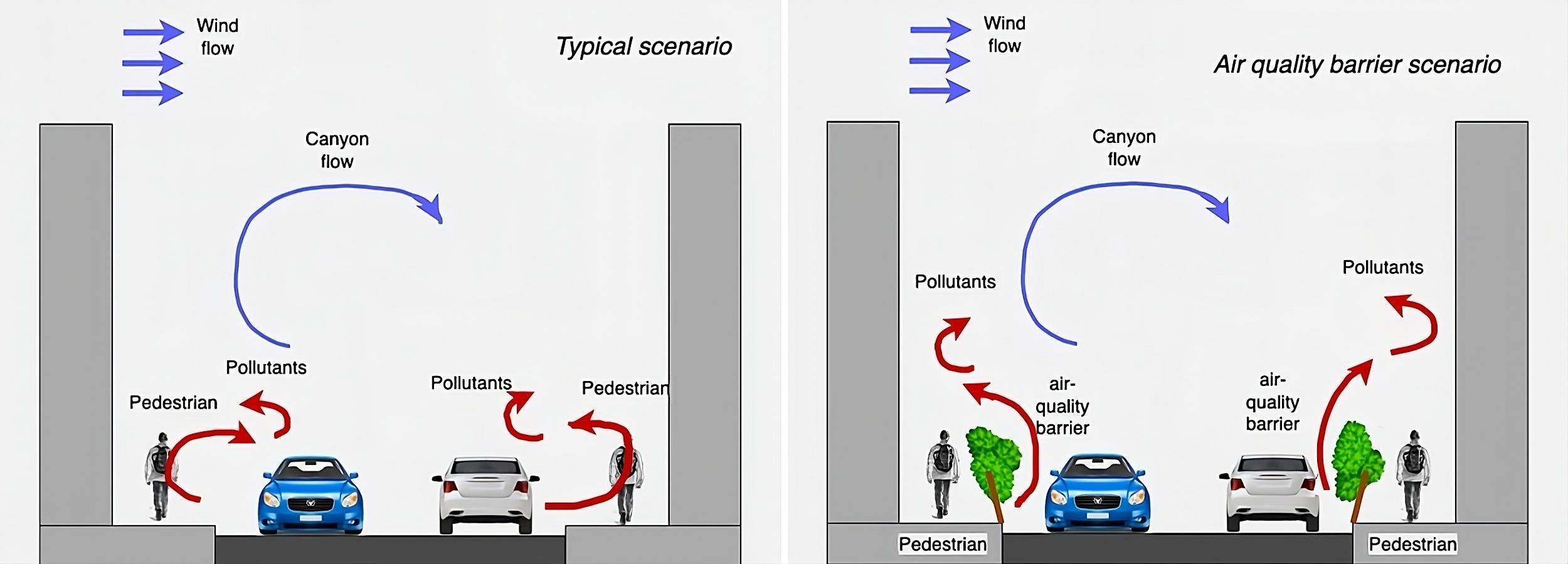

The project focuses on studying Rue D’Argens, a ‘street canyon’, which is a typical city layout characterised by densely packed buildings around roads. When wind flows through the street canyon, it generates a distinct airflow pattern, circulating air within it and dispersing pollutants emitted by vehicles in a particular manner. Pedestrians in these zones are consequently exposed to contaminants.

The project’s goal is to build barriers to shield pedestrians from these pollutants. These barriers can take various forms, such as planters for landscaping. Duca and Micallef agree on vegetation’s limitations and are testing solid versus green barriers. However, Micallef also considers aesthetic benefits while looking for the best solutions possible. Factors such as the vegetation’s porosity directly impact contaminant concentrations in pedestrian zones. Therefore, the project is looking into optimising these parameters and selecting appropriate vegetation types to minimise pollutants in pedestrian areas.

The Methodology Behind APACHE

The year-and-a-half-long project is currently in the testing phase, wherein the team has employed two methodologies together with citizen feedback to inform the design. The first method uses simulation tools to predict air behaviour in the presence of barriers, while the second one involves wind tunnel testing. This offers insights into the airflow around the barriers. Micallef emphasises that these testing models provide a good estimate for real-life, full-scale predictions.

Researchers use particle image velocimetry – a way to measure the speed of air in a specific direction. In this case, the technique could measure how the air flowed around different barriers the researchers created based on citizen feedback. This means that the method does not include, for instance, fans or any active way of removing pollutants. The amount of pollutants will remain the same but away from pedestrians using the street. Duca also notes that one of the most promising findings is a barrier combining concrete and plants, as both materials effectively disrupt the flow of pollution, preventing high concentrations and minimising dispersions.

Adopting a Co-Creative Process: Research Shaped by Citizen Feedback

A cornerstone of this project is community co-creation and involvement, which is put into practice through workshops to gather ideas about design limitations. Based on the feedback collected from residents in Gzira, researchers determined practical and reasonable parameters for implementing the project, such as the type of barrier (natural or artificial), height and so on, ultimately aimed to upscale solutions and field-test them upon approval to help citizens using Maltese streets.

Beyond the Project: Exploring Future Avenues of Research

The project’s main objective is to validate and demonstrate the effectiveness of natural barriers. According to their preliminary simulations, Micallef highlights that a fully vegetated barrier outperforms a solid wall. That said, further testing in the real world is necessary, especially to consider whether a barrier that combines concrete and vegetation would perform better. The researchers hope to secure further funding to test their results thoroughly. Besides keeping pollution away from pedestrians, these barriers have the added advantage of making our streets look better! Let’s hope that we’ll be seeing these barriers in action in the near future so that taking a walk keeps us healthy.

The project is funded by the Malta Council for Science and Technology under the Fusion Smart Cities programme.

Comments are closed for this article!