Water is the last resource. The politics, deprivation and conflict created by water insecurity will define the future. Malta, as one of the most water-stressed countries in the world, will be ahead of the historical and technological curve. Jonathan Firbank looks ahead.

‘Water, water every where, nor any drop to drink’, lamented Coleridge’s becalmed mariner. How like his stranded ship is crowded Malta, with neither rivers, lakes nor frequent rain. Water is kept in its holds: storage facilities and natural aquifers that protect their cargo from Malta’s ‘hot and copper sky’. Malta’s geographic limitations make it the most water stressed country in Europe. Those limitations will narrow. As the world gets hotter, Malta will experience more demand for water. As aquifers deplete and sea levels rise, more of Malta’s natural groundwater will be contaminated by salt. Malta will be squeezed by both upward and downward pressure. But the problem is not Malta’s alone. Water insecurity is an albatross around the neck of the whole world. Malta is a forerunner, a microcosm of a growing, global crisis. This means it is uniquely positioned to trial countermeasures. It will experience this drought early, and will field test the technology needed to overcome it.

Drought Warfare

Malta’s geography is particularly inhospitable to freshwater, but it will not experience the most extreme consequences of this growing crisis. The apocalyptic scenes we associate with drought are not likely in Malta any time soon. The island is well integrated with global supply chains. Additionally, its place in the European Union motivates allies to participate in its survival. Most importantly, it is extremely unlikely that Malta will find itself at war. Over time, it’s becoming clear that the only thing worse than not having enough water is having your water supply controlled by an adversary.

Flashpoints for future wars are appearing across the planet. As the incidence of drought rises, where one country controls the water supply of another, there is an increasingly existential pretext for conflict. Turkey has dammed the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers, intentionally parching hundreds of thousands of people in Iraq and Syria.1 India has dammed the Indus, imperilling Pakistan, and is challenging the water rights treaty that has kept those nations from war.2 Ethiopia has dammed the Nile, interfering with Sudan and Egypt’s lifeblood.3 A swathe of similar flashpoints are emerging across Central Asia as outdated, Soviet water-sharing agreements degrade.4

Freshwater deprivation is not just a cassus belli, it is also a means by which to wage war. It is already being used as a weapon in today’s three most violent conflicts. In addition to Turkey’s warcrimes in Syria, Israel is withholding water from millions of Palestinians5 and targeting humanitarian aid that might relieve them.6 Russia destroyed Ukraine’s Kakhovka Dam. This drained canals that provided water to people that, again, numbered in the hundreds of thousands.7 Ironically, the fallout even extended to Russian-held Crimea.

Outside the countries victimised by these vile tactics, there is little understanding that climate change related problems can be caused by human intent as well as human negligence. This will change as drought is maliciously leveraged more and more. The silver lining to this darkest of clouds is that war drives technological development faster than climate change ever has. In the future, Malta may depend on innovations paid for in blood. In turn, those innovations, should they arise, may be evolutions of technology Malta uses today.

Water Technology

Malta has employed technology to stave off water deprivation for over 8000 years.8 In neolithic times, cisterns were cut into cavern rock to collect rainwater. Over millennia, these were joined by progressively more advanced subterranean reservoirs. This included those mandated or built by the Knights Templar and British Empire. The end result is that one of Malta’s great architectural marvels, an effort spanning cultures and aeons, is not just underground but also underwater. Now, they are joined by storage facilities attached to Malta’s groundwater pumping stations and seawater desalination plants. These are Malta’s primary water sources, and the balance between them is leaning ever further towards desalination as Malta’s underground aquifers are overexploited.9

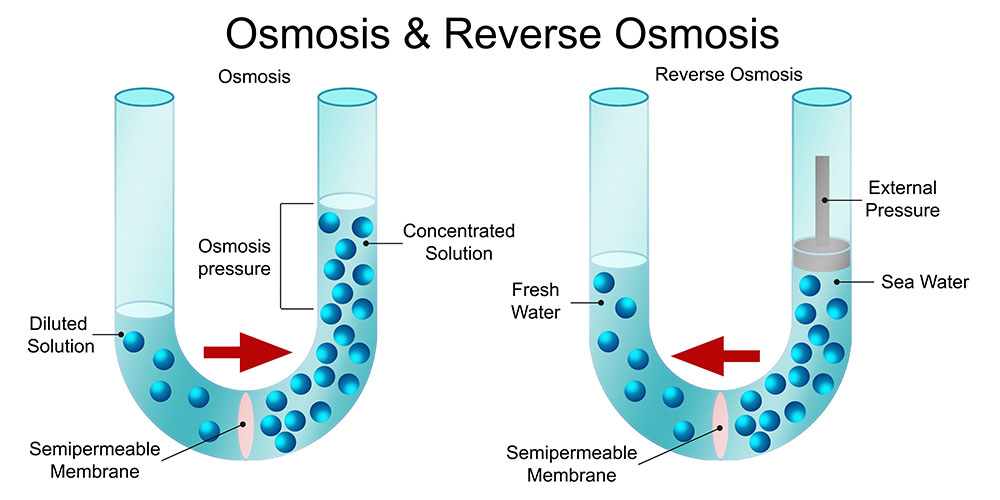

The core technology behind each method is unlikely to be revolutionised. Groundwater extraction requires a drill and a pump, while desalination depends on a process known as reverse osmosis. This sounds complex, but it essentially just means pushing seawater through a filter for salt and other substances. These will both continue to be refined, but each has a core flaw that must be overcome with secondary technologies.

Draining the Earth

Groundwater is a deposit of freshwater – in Malta’s case, rainwater. This accumulates in porous rock and other naturally occurring, subterranean openings. It is finite. Malta’s groundwater has built up over a staggeringly long time and is now being rapidly depleted.10 The more is extracted, the worse the quality of the water. It is progressively more salinated the deeper you get as saltwater is denser – a nearly empty groundwater deposit could be more toxic from salt than seawater. Nor is that the only way these deposits can be contaminated with salt. As the sea rises, it finds its way into groundwater deposits through openings that were once above sea-level.

In strictly technological terms, the future of Malta’s groundwater simply depends on finding more of it. At UM, innovations are being made using sound waves to detect aquifers.11 In addition to being extremely efficient this bypasses the expensive process of exploratory drilling. The latter is particularly destructive in a country that is so archaeologically rich and so vulnerable to seismic events. Another UM-led initiative has discovered evidence of groundwater below the sea floor, off Malta’s coast.12 This could provide 70 years’ worth of water but demands advanced hardware to access and extract. Ultimately, the cost-benefit ratio will swing far enough that these tools are developed, either in Malta or another sea-adjacent state.

But there can only be so many unexploited aquifers in Malta’s small territory. Malta needs to protect what’s still there more than it needs to find more of them. To that end, there is a need for political technology. Malta’s groundwater is often drilled and extracted illegally, which makes it impossible to regulate. It is largely stolen by criminals in the agriculture and construction industry.13 Agricultural spaces are comparatively remote, demanding active scrutiny. Conversely, construction industry criminality happens in plain sight but is sycophantically ignored. Malta will need a greater capacity to enforce law, lest its industry cross the finish line in this race to the bottom.

Drinking Seawater

Then there’s desalination, a technology that sustains nations with the most hostile environments. It suffers from a simple problem – it demands a vast amount of energy. This makes it very expensive and, ironically, very bad for the environment while over 3/4s of Malta’s energy comes from fossil fuels.14 Future iterations of this tech will be more efficient, but forcing vast amounts of liquid through a membrane will always demand a lot of energy. It will only be sustainable once the energy infrastructure supporting it is sustainable, whether that be domestic or imported.

A crucial resource that Malta is already tapping into is greywater, the comparatively clean wastewater such as is produced by sinks and showers. This water can be easily recycled, requiring minimal treatment before it becomes usable in many spaces with high demand. Crucially, this includes irrigation and concrete production. Initiatives in Malta, such as Project NOMAD are already supplementing farming with treated greywater,15 a practice that can only grow as freshwater supplies decrease. Greywater can also replace a proportion of the vast amounts of freshwater used in concrete without undermining its structural integrity, as proven by a study last year.16 Any percentage of freshwater saved from Malta’s endless concrete production would be a huge boon to the nation.

Tomorrow’s Island

Strain on freshwater capacity will have radical variances between nations. In the deserts of those worst affected, there are deceptive mirages. The wealthy oil economies of the Gulf can brute-force their way through their water scarcity, pouring money and energy into performative cities to create an illusion of sustainability. Elsewhere, their exports’ massive carbon emissions will cause nations to collapse into humanitarian crises, leaving no lessons for the rest of the world. Malta is different. It has contended with water scarcity since before we invented the wheel. Now, it is a stable, democratic state that applies cutting-edge technology despite a small economy. Malta – past, present and future – will inform the rest of the world about water scarcity and how to fight it. But Malta must also inform itself. It has less time to deal with water insecurity than most other nations, but its political and industrial inertia does not match that urgency. Things seem deceptively calm in the eye of a storm.

Comments are closed for this article!