Nicholas Mamo has developed an algorithm that analyses Twitter feeds and extracts information about events. This type of artificial intelligence has been designed to automatically identify the participants involved in the events and understand what happened based on the tweets.

In recent years, the concept of artificial intelligence (AI) has teetered in people’s minds between an all-saving, problem-solving solution that will lead humanity into the next age of its evolution, and a cataclysmic catastrophe waiting to happen which will bring about the destruction of everything we know. Hollywood may have added fuel to the fire by instilling in our society’s collective consciousness the idea of a supremely sophisticated algorithm becoming sentient and overwhelming its own creators.

In recent years, research laboratories such as OpenAI, with its introduction of ChatGPT, have raised ethical and legal issues involving, amongst others, copyright, privacy, and transparency concerns. At the same time, AI has become an indispensable resource in fields such as business marketing and decision-making strategies – not to mention the innumerable advantages of reducing human error.

AI as a News-Gathering Tool

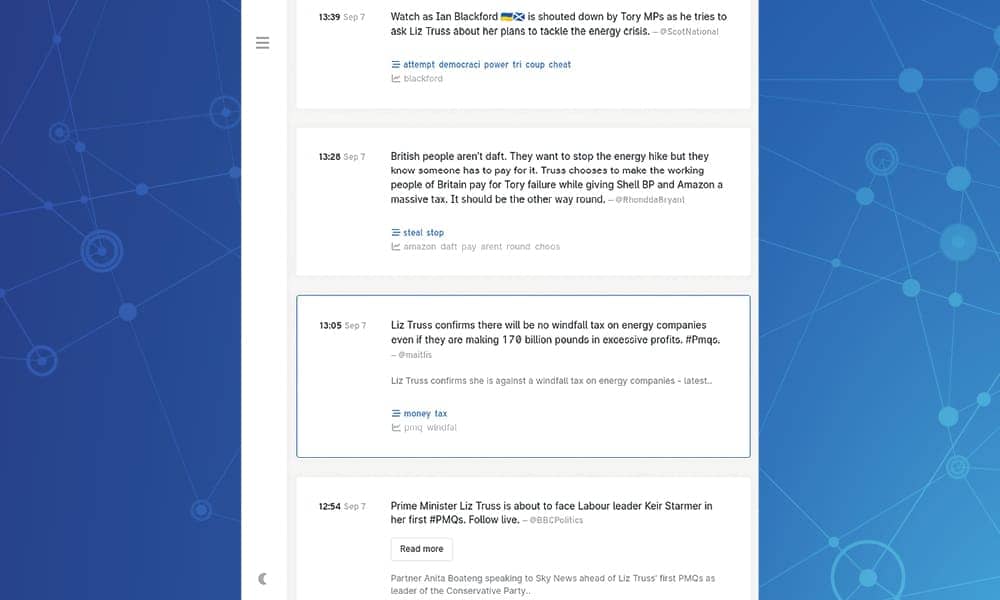

Nicholas Mamo, a Ph.D. Graduate and researcher in AI, has harnessed the power of this growing technology and applied it to computational journalism. As part of his doctoral research, Mamo developed an algorithm enabling him to analyse a vast array of feeds on the social networking platform Twitter. The algorithm can automatically identify and extract information as well as details on what is being discussed—outlining the type of event, for instance, and the participants involved. This news-gathering code enables users to sift through millions of tweets related to a specific event while constructing a timeline of what is happening – providing a step-by-step report as the event unfolds. ‘We would look at what people are talking about or how they are talking about the news.’

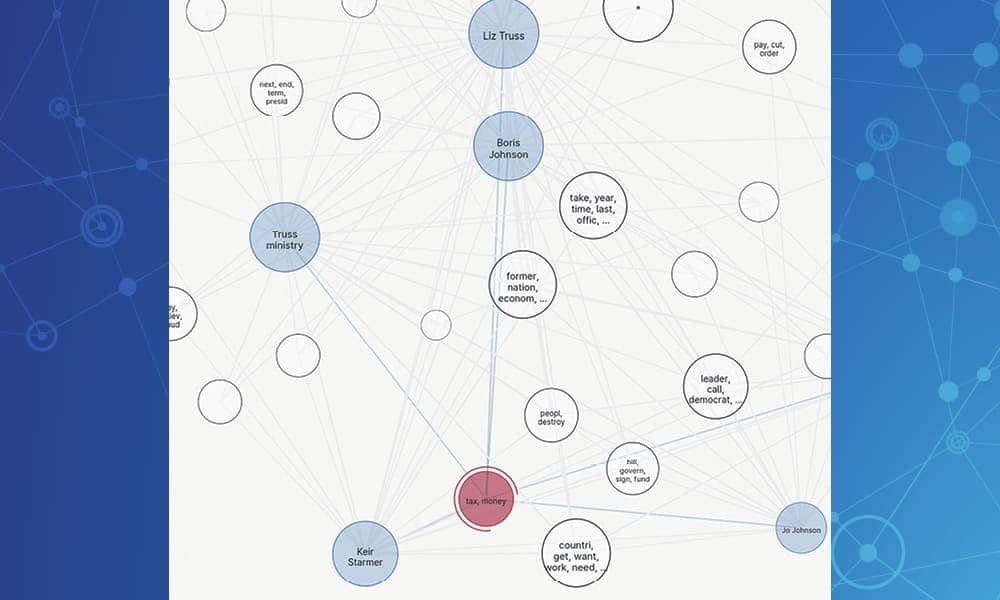

Mamo provides the example of a football match scenario that involves thousands of people – mainly spectators – utilising the online platform to report what is happening during the game. ‘News is news. News does not change. So if you are watching a football match, you know what will be important: if somebody scores a goal, if someone receives a yellow card, etc. The idea was that, if we understood events better and if we have domain-specific understanding, we can improve our algorithms.’ In this football match example, the algorithm collects all the tweets related to the game, analysing each in turn and constructing a detailed timeline of the match from start to finish, whilst also building a knowledge graph that merges all the details together. Event Tracking is a crucial part of this process, as it generates specific data and statistics that reflect both the engagement of social media users and current online trends in general – enabling journalists and news reporters to access and utilise the coverage of specific events more effectively.

A Tool for Journalists and News Reporting

One of the crucial functions of this Event Tracking algorithm is the ability to eliminate ‘noise’ and irrelevant details gathered from tweets, and to single-out the most important markers during the data-collecting stage. ‘If you know that goals in a game are important, then you can just focus on goals. Whilst in elections, if you know that speeches and campaign rallies are important, you can focus on those keywords.’ Journalism, which relies heavily on analysing such data – especially on social media platforms – to assess ongoing events, public figures, and generic reporting, benefits from this type of technology. ‘There is a more practical aspect for journalists,’ says Mamo. ‘It is very difficult to go through millions of tweets. So they need something, not just to detect breaking news, but also to make sense of it.’ Mamo recalls how he had been working on this program for three years prior to starting his Ph.D. ‘I had a clear idea of what problem I wanted to solve.’ In fact, this issue of domain-specific understanding has been attempted for around 20 years, but those efforts proved largely unsuccessful. That was when Mamo decided he had to develop his own theory to find out what worked and what did not.

Providing another scenario from the US political sphere, Mamo delves deeper into how the AI algorithm was programmed to accurately identify participants involved in events that are mentioned in tweets. Using the election as an example, someone like Joe Biden is identified as a participant, and within the thousands or millions of tweets, the algorithm extracts what are known as Named Entities – in other words, a person’s name. ‘What is new in this research is that we are trying to understand which of these names are actually participants, and to do that, we extracted their attributes – basically, who they are and what they do. For example: Joe Biden is an American politician and They serve as a President‘. These attributes are then used to look for other names and persons that share these same attributes. ‘If we follow American politics and notice that most participants are politicians, then we can reasonably assume that other politicians are related to this election.’

Misinformation and Ethical Considerations

With the processing of vast amounts of data, allowing an algorithm to sift through and identify participants and events, the question of misinformation becomes a major concern. When it comes to the algorithm itself, however, Mamo admits that there is always the risk of the spreading of such misinformation. ‘It is harmful, but it is not very common. Sometimes you capture it, but it is usually a genuine mistake. What is important, especially with news, is that sometimes you are going to capture misinformation, and it is very difficult to filter it out, because you need to understand the whole context. However, it is equally important that you also capture corrections to it.’ In order to minimise misinformation, the algorithm employs several techniques as it sifts through the data, one of which involves filtering out tweets that exhibit spam behaviour. Ultimately, the way the algorithm works is that it is geared towards confirmation by cross-referring the data and ensuring as much as possible that it is correct.

‘Ethically, there is no harm at all,’ reassures Mamo when THINK asks about the ethical considerations of this algorithm when it comes to people’s privacy and personal information. ‘We can only use public tweets and therefore only content that was purposely put out.’ The way a social media platform like Twitter works is done precisely to protect its users. Every tweet has a unique identifier, which means that researchers, such as Mamo, can only use those identifiers which are public.

News Does Not Change

‘We’re seeing the evolution of the entire social media,’ says Dr Joel Azzopardi from the Department of Artificial Intelligence at the University of Malta. Together with Dr Colin Layfield from the Department of Computer Information Systems, Azzopardi supervised Mamo during his doctoral research. To this end, the AI algorithm allows for flexibility in its use, and can be developed and implemented in other sectors. It all goes back to that adage Mamo began with: that news does not change. What people are discussing and talking about on Twitter is the same across other social platforms – keywords and participants are utilised similarly throughout the entire news spectrum, and as Mamo further explains, the important factor is this domain-specific understanding. ‘We very easily could put our algorithm not just to other domains but also to other social networks.’

In a digital world that is becoming increasingly fastpaced, with a social networking system that is evolving day by day, the sophisticated resourcefulness of AIfuelled algorithms can step up in the processing and filtering of data to keep up with the demand for news and information that is globally connected. AI may have two sides to it, but far from the world-ending scenarios we are often exposed to, the benefits appear to be outweighing the harms… at least for the time being.

The research work disclosed in this publication was partially funded by the Tertiary Education Scholarships Scheme (Malta).

As of 23 July 2023, Twitter has been renamed X.

Further Reading

Further Reading

Gordon, C. (2023, May 2). Ai ethicist views on Chatgpt. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/cindygordon/2023/04/30/ai-ethicist-views-on-chatgpt/

Kumar, S. (2019, December 12). Advantages and disadvantages of Artificial Intelligence. Medium. https://towardsdatascience.com/advantages-and-disadvantages-of-artificial-intelligence-182a5ef6588c

Myers, S. L. (2022, October 14). How social media amplifies misinformation more than information. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/13/technology/misinformation-integrity-institute-report.html

Needham, A. (2023, June 8). All about ai: Why it’s indispensable to business marketing. SPD | University of Salford. https://www.salford.ac.uk/spd/all-about-ai-why-its-indispensable-business-marketing

Comments are closed for this article!