Museums are a portal into the past. To create a sustainable future demands understanding and learning from this past. From Art Strikes to Biomimicry, Sandro Debono explains how many modern museums are taking a more active role in shaping the way our future unfolds.

My museum and curatorial practice have always been informed by theory and hands-on practice. Thinking through problems to find appropriate solutions informs my practice throughout, and recent circumstances have made me aware that this has become a highly sought-after skill. The COVID-19 pandemic can be seen as a negative disruptor. I prefer, instead, to consider the silver lining whereby the pandemic becomes an accelerator for change. The silver lining is for that potential for change to happen in significant and tangible ways — which is where museums come into the picture.

We rarely think about museums as public spaces where collections become resources that inform discussions and rethinks of long-established narratives and perspectives oftentimes considered by many as cast in stone. The museum is often understood as a tangible metaphor or a stereotypical idea rather than a response to the needs of a particular ecology to which it relates and responds to.

At the other end of the spectrum, climate action has been on the national agenda in fits and starts, with the country now unveiling an ambitious climate action plan to achieve net-zero emissions over three decades. Perhaps the most symbolic action is the unanimous declaration of a climate emergency by Malta’s national parliament in 2019. The reduction of greenhouse gases and extensive use of renewable energy resources has been on the national agenda for close to a decade or so. There is no question that Malta will be impacted in one way or another through rising sea levels and other effects. There is much that needs to be done, and the willingness to address this ever-pressing challenge requires increased awareness and outreach. Museums and climate action are far from being dissonant, disconnected voices. Indeed, one can become the voice of the other in meaningful ways.

Climate Action Advocacy

Museums have a voice. They also have things to say that are equally relevant to the present as much as they are to the past. One of these pressing matters, temporarily displaced to the shade of the COVID-19 pandemic, is climate change and the ever-more-pressing need for action. The obvious choice of institutions to take action would be science and natural history museums. Indeed, the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Natural History (part of the International Council of Museums), has been exploring ways and means to stimulate conversations about climate change. The international museum landscape has welcomed new museums dedicated to climate change in Hong Kong (Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change), Germany (Klimahaus 8°), China (Low-Carbon Science and Technology Museum) and Oslo (Klimahuset) since 2013. The entire international museum landscape has been active on this issue for quite some time. An ever-increasing number of museums have featured climate change in their public programming, and some are joining forces more than ever before. One example is the Coalition of Museums for Climate Justice, mobilising Canadian museum workers and their organisations to develop public awareness, mitigation, and resilience in the face of climate change.

Last year, the Museums for Future movement was launched. It is a global collection of museum workers, cultural heritage professionals, and many others in support of Greta Thunberg’s Fridays For Future Movement.

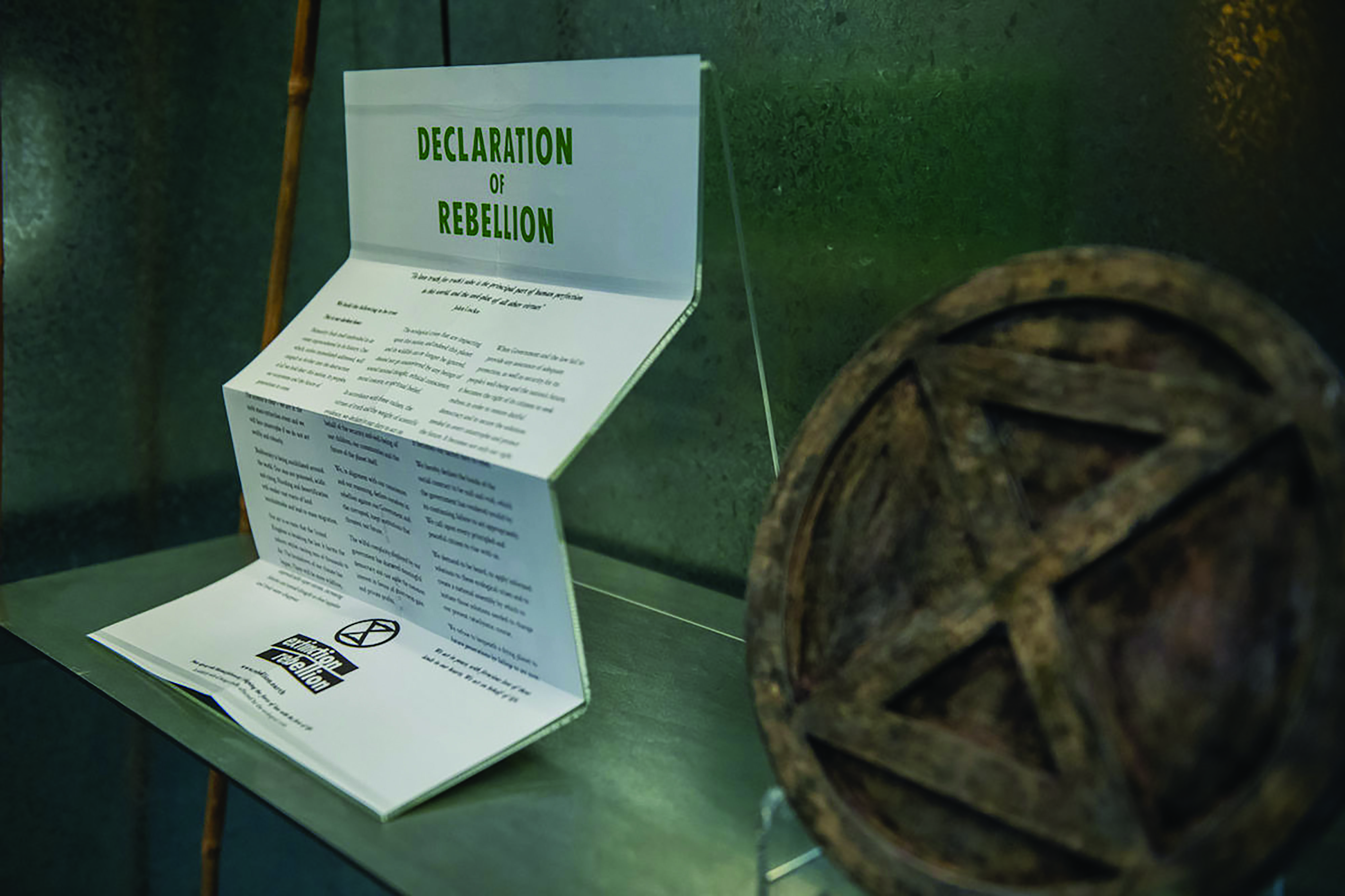

Museums can be both advocates and activists. One particular action hitting the headlines, also promoted by Museums for Future, is the art strike. This works by museums covering artworks on environmental subjects or themes for a day. The platform has a toolkit to guide and support institutions interested in calling art strikes. The Victoria and Albert Museum took things one step further. It partnered with Extinction Rebellion, the activist group calling for urgent climate action, to present exhibitions featuring material culture created for the purpose of protest. Since then, the museum has acquired artefacts produced for the purpose of protest, comparing the visual impact of the group’s campaigns to that of the suffragettes.

The Environment as Mentor

Protests have a flipside. Museums can become more aligned to natural processes. Museums can reduce their carbon footprint. Another step is to recycle and use eco-friendly materials in exhibition displays. Aligning museum institutions and their role in contemporary societies as public spaces is where biomimicry thinking comes into the picture.

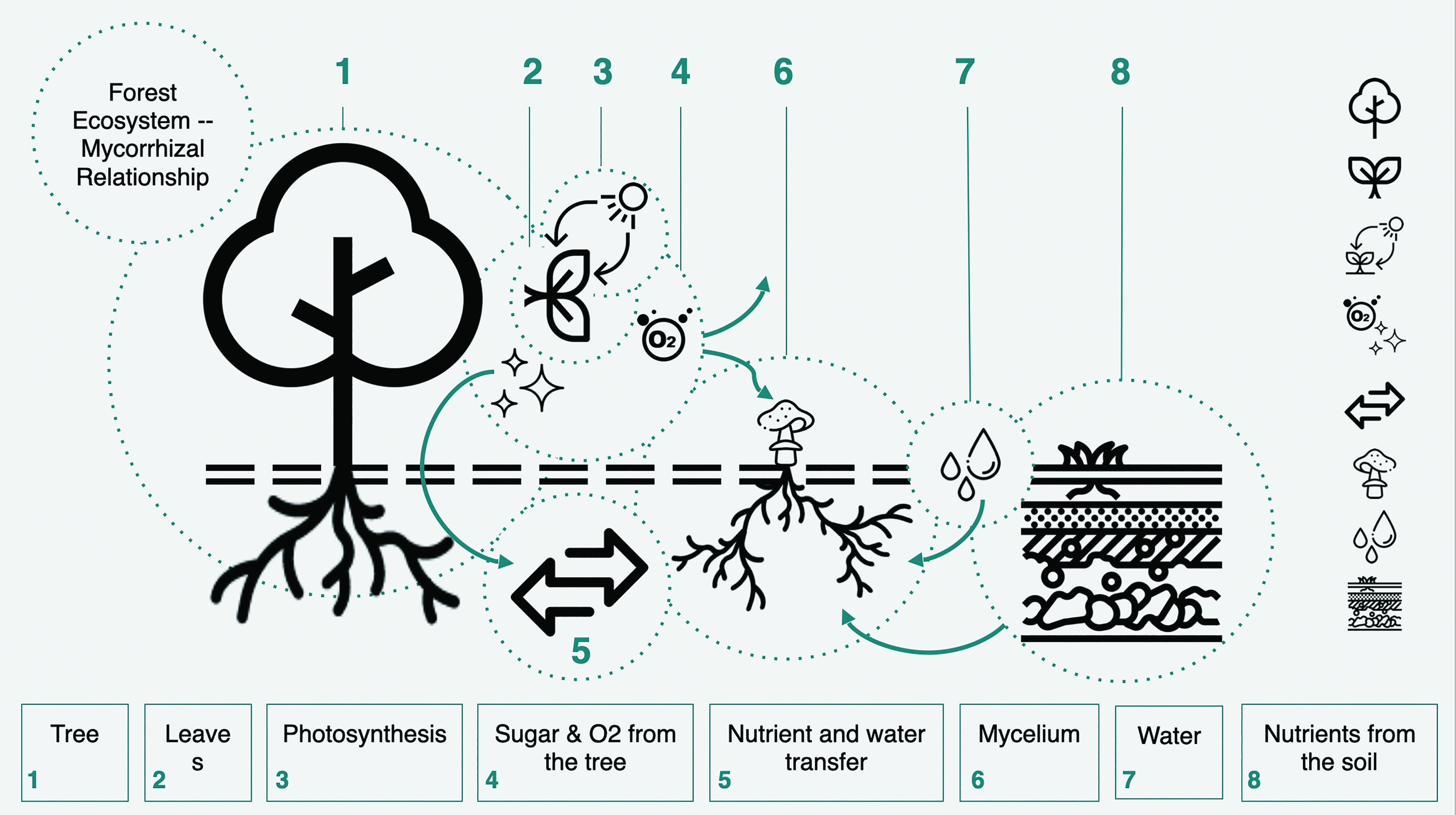

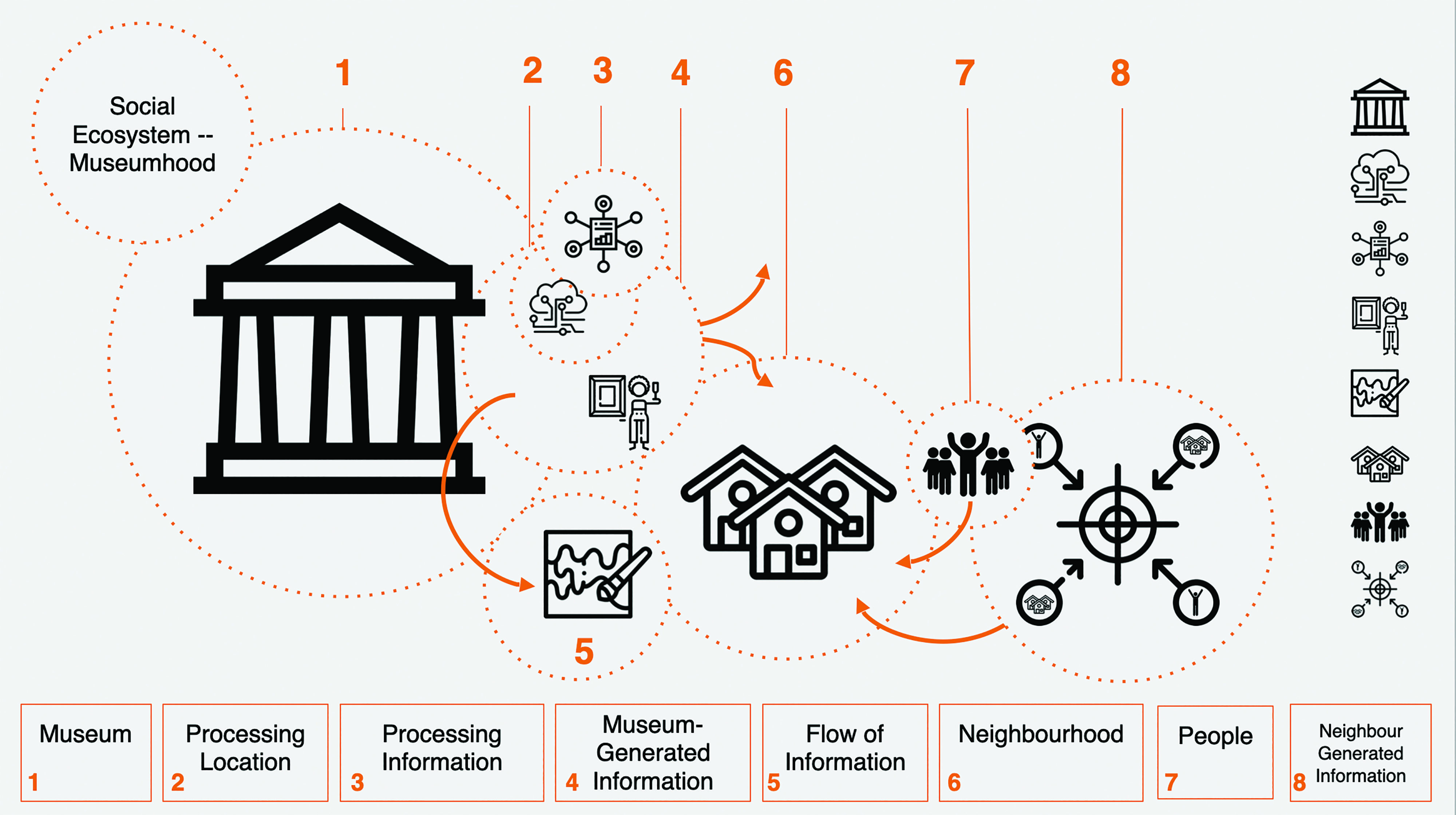

Biomimicry is an approach to innovation informed by adopting strategies found in nature for the purpose of developing sustainable solutions to human challenges. Janine Benyus’ book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature (1997) popularised this thinking. For biomimicry, innovation is informed by the natural world, leading to rethinking workings, management models, programming, and outreach. It is about the willingness to shift from ‘how might we’ to ‘how would nature’ do it in order to understand the underlying principles of nature for museums to create symbiotic relationships with their neighbours.

Biomimicry thinking can inspire museums to adapt, rethink, and reinvent themselves. Biomimicry can help museums understand the ecosystem they exist in and how it differs from nature. The institution would also need to translate science-driven and nature-informed biological data into design principles. Impact and sustainability would need to shift from the yardstick of efficiency and numbers, to the extent of systemic innovation introduced and the impactful change it has on the museum.

By looking closely at natural ecosystems, we can reinvigorate and reimagine the way museums operate, expanding their outreach and engagement in sustainable and innovative ways.

Further Reading

Museums & Climate Change Network. Museums & Climate Change Network. Retrieved 1 November 2020, from https://mccnetwork.org.

Museums For Future – Culture in Support of Climate Action. Museumsforfuture.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020, from https://museumsforfuture.org.

The Biomimicry Institute. Biomimicry.org. Retrieved 1 November 2020, from https://biomimicry.org.