But what does real really mean? Is there only one reality or are there multiple realities? These questions have been asked over and over again ad nauseum throughout humanity’s history only to end up with the same paraphrased answer: ‘Dear Sir, we can’t give you a definite answer since up to now we are not sure enough of what we are really speaking about.’ Socrates said reality is One, The Matrix says that the reality we experience is an illusion, while Stephen Hawking argues that reality is made up of distinct sets of laws of physics interwoven together into what he — plus a few other scientists — calls M-Theory.

Indeed the digital era has not improved the situation. What was once the domain of the tangible and spiritual world ended up expanding exponentially into virtual worlds entirly created by humans — a hyperreality! Indeed the hyperreal has found its way in the visual arts. In the 60’s Photorealist painters created paintings indistinguishable from photographs. Their succesors, the Hyperrealists, depicted photoreal realities that never actually happened.

How can a painting feel more real and tangible than reality? Up to the beginings of the last century mimesis (roughly means to imitate) was one of the main preocupations of western art. Artists made use of various visual tricks such as perception, occlusion, and chiaroscuro to fool the eye and give life to their works. But no matter how hard they tried they were doomed to failure because in an instant the brain would discover the illusion and reveal the flatness of the painted surface. The reason is simple, painted surfaces are monoscopic, from one point of view, whereas the brain builds a picture from what two eyes see to understand space and depth, a binocular system.

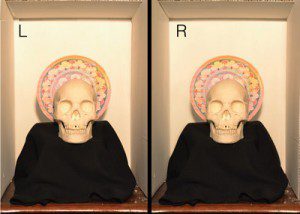

For this reason, Darren Tanti harnessed binocular vision to his advantage and implemented stereoscopic principles into his paintings to create 3D images. 3D images form in our brains when two images (a left and a right image) are set slightly apart. Our brain fuses the two images together giving the illusion of depth and form. The trick is to recreate the two images onto the same canvas with two different paints, to align them slightly apart as precisely as possible, and to calibrate colours to match the colour filters of 3D glasses. The right combination of all three creates a fully functioning 3D painting.

At first glance, 3D artwork might seem simple but there is a lot of work behind it. This technique cannot be used for its own sake. By combining it with other drawing or painting methods then there is a good chance to break ‘through the looking glass’ and enter a whole new world.

| Give it a try |

Below is a simple method to create an anaglyph 3D image. Words by Darren Tanti

|