The rapid advancement of technology has transformed us into The Jetsons. But the use of these tools to enhance our storytelling makes us seem more like The Flintstones. Writers, creators, producers and academics are still busy developing ways to create richer, more engaging and more profitable transmedia experiences. Dr Jean Pierre Magro speaks to Think on the fascinating and lucrative world of transmedia narratives. Illustrations by Sonya Hallett

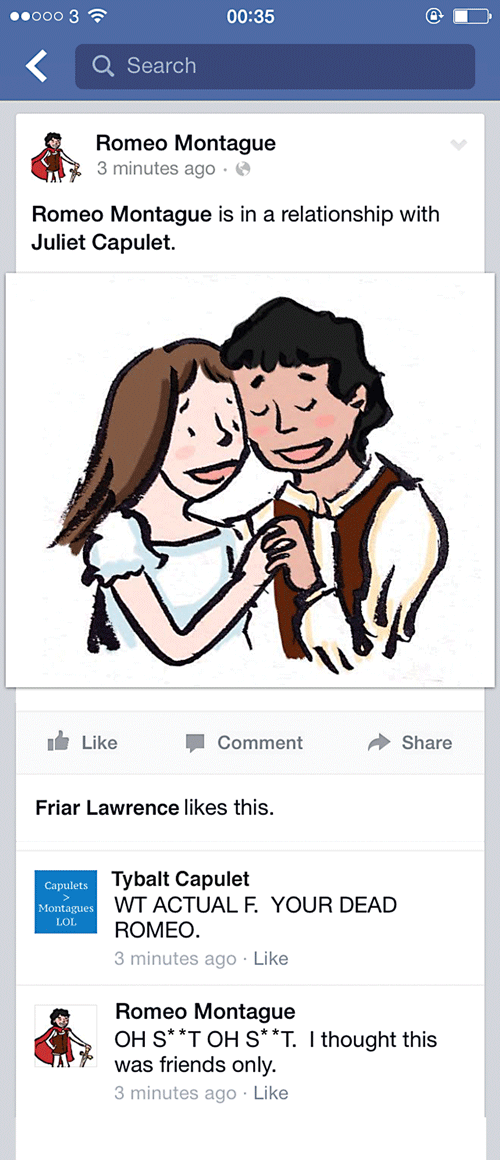

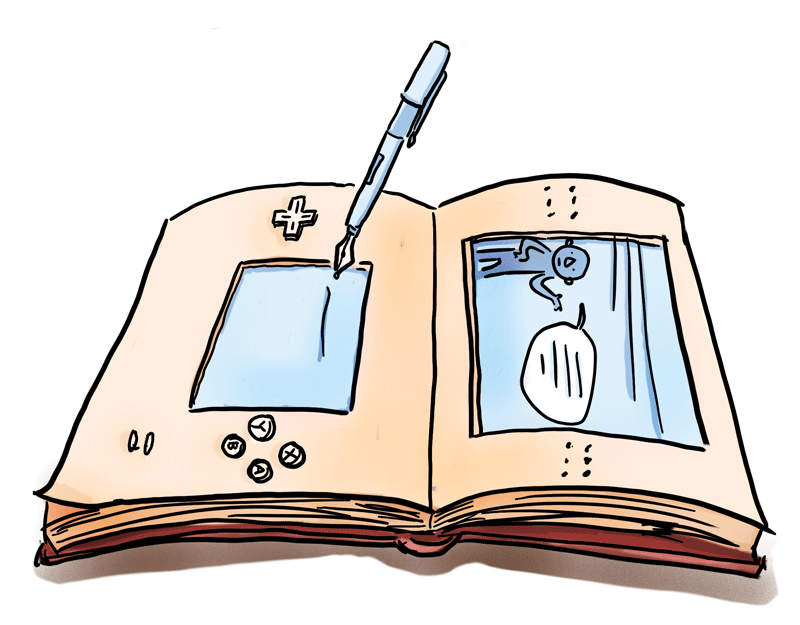

Storytelling is in an exciting period of change. New narrative forms are being created daily. Producers, due to a range of different platforms, are able to expand their canvas and share more of their vision with the most dedicated fans. They can achieve this by creating and designing multimedia narratives from the ground up in which movies, video games, websites, smart phone applications, comic books, and other media are equal chapters of a complete story. This is transmedia storytelling.

My transmedia story began in 2009 while working as Head of Development in Los Angeles with US/Spanish outfit FishCorb Films. This emerging ecosystem of texts and para-texts, and their organisation, became a personal obsession.

But while I consumed the literature available, attended seminars, and formulated a slew of ideas to apply this new concept to existing projects, I hit a snag. While I was ready to experiment and see the effect of transmedia on our audiences, my bosses, and financiers held me back, unwilling to invest against the high risk of the unknown.

It was then that I decided to shelve my career in Hollywood and return to Europe to test and play with the form. Media studies become essential during periods of disruption and transition, offering a sober analysis of the situation, while continuously suggesting various alternative paths. Therefore, the next logical step for me was to enrol for a Ph.D.

With backing from STEPS, I started a three-year journey focused on unravelling transmedia and its functions.

Transmedia is no longer a mere buzzword or some millennial sideshow distraction, but an important reality of the global entertainment industry. Audiences and their behaviours have changed drastically over the last five years. The ‘lean back’ approach is being replaced by the ‘lean in’ approach. People want to be in control of their media, deciding when to watch what and on which device.

Experts believe that the companies which will survive in this landscape are those with the ability to understand and speak to the needs of their audiences. Producers today need to know how to keep audiences satiated and engaged. These particular skills will become essential to their success. Whether producers like it or not, they are increasingly dependent on networked communities to circulate, curate, and appraise the final product. In reality, they no longer have any control over their content from the moment it leaves their hands.

The basic premise of transmedia storytelling is that instead of using different media channels to simply retell the same story, each channel is utilised to communicate different elements of the story. Each segment should stand on its own, while also contributing to the narrative as a whole. Each segment should add new pieces of information which forces the audience to revise their understanding of the overall narrative.

Transmedia storytelling offers a real feast for postmodernist writers who, like James Joyce before them, love to challenge an audience by inviting them to construct their own text from the fragments provided.

For me, transmedia is an art form that invites the audience to become an active participant of a ‘world’. While each different segment needs to be unique in its own right, these extensions must also uphold the canon, style, and tonality of the primary text. Each extension needs to play a vital part in the telling of the entire narrative, creating a richer experience. However, this can only be achieved if properly planned, with each component acting very much like a sequence in a screenplay, each one building on the other in a coherent structure, enhancing the consumer’s experience.

“Transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience. Ideally, each medium makes its own unique contribution to the unfolding of the story”

The real issue with transmedia is that it lacks its own proper grammar. Even the term transmedia is still open to misinterpretation and hegemonic discourse. There is no set of ‘standard best practices’ yet. This became very clear during various conference and seminars, including Power to the Pixel in Potsdam and London, Storyworld in San Francisco, and the Torino Film Lab. Professionals are experimenting with the form, attempting to find a method which works, that can then be replicated and sold to investors.

All of these reasons pushed me to focus my Ph.D. on attempting to create principles which could contribute to the establishment of a set of standard best practices.

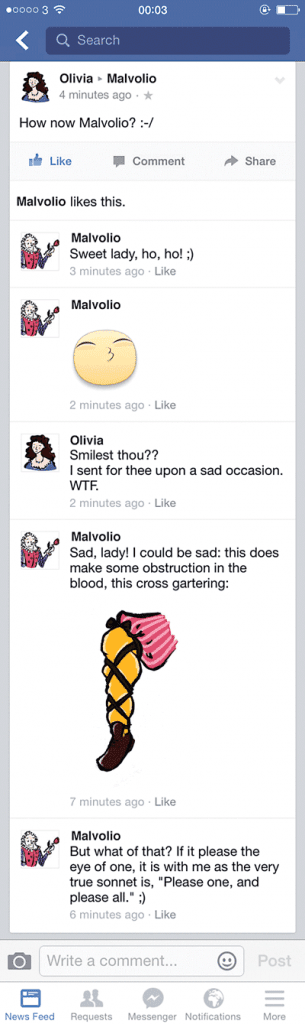

From my interviews with other professionals, it became clear that storytellers have been unable to fully exploit the possibilities at their disposal. Many lack the necessary knowledge and skills to maximise the potential of their stories across various platforms. It is not easy to understand how the combination and coordination of so many different disciplines can offer an exciting experience. In many cases, transmedia has been reduced to a mere business plan. Marketing teams seeking to expand their text as far as possible, encourage audiences to consume the same IP (Intellectual Property) from different outlets, wrongly calling it transmedia.

From my interviews with other professionals, it became clear that storytellers have been unable to fully exploit the possibilities at their disposal. Many lack the necessary knowledge and skills to maximise the potential of their stories across various platforms. It is not easy to understand how the combination and coordination of so many different disciplines can offer an exciting experience. In many cases, transmedia has been reduced to a mere business plan. Marketing teams seeking to expand their text as far as possible, encourage audiences to consume the same IP (Intellectual Property) from different outlets, wrongly calling it transmedia.

A prime example is The Hunger Games, one of the most successful film franchises of 2012. After the release of the first film, a series of poor tie-ins were released, none of which did anything to enhance the story, the characters or the world. Instead, the would-be transmedia components morphed into silly puzzles, games, blog competitions, toys, nail polish, and other merchandise. Such thoughtless entertainment can easily be equated with fast food. Transmedia is being ‘McDonaldised’.

The transmedia label is often applied indiscriminately to anything that is even remotely interactive, participatory, pervasive, or multi-platform. Confusion arises, in part, because the field is so young. The term transmedia is very often used to make a product sound more innovative than it actually is. This is expected, especially when considering the enormous capital investment at stake. The media industry is big business.

As an international producer, I always felt the need to analyse and make sense of this particular moment in time. Transmedia storytelling remains a murky term, with new vocabulary sprouting on a regular basis. This again shows just how sparse ‘industry standards’ are within transmedia. The difficulty in finding the appropriate terms to use is an immense problem because it makes it extremely hard for creators to explain what they are selling. Consequently, attracting investment becomes practically impossible.

I always like to compare transmedia’s present with the early days of TV. Not knowing what to do with cameras, producers solved their quagmire by filming radio shows. Soon after, industrious people realised the tools’ potential. As time went by, a new language was created, more eloquent and sophisticated. At the moment, many transmedia practitioners are still applying a single medium mindset to the form.

Transmedia storytelling needs to become a recognisable and repeatable product. My contribution to this argument was to apply a known concept—the eight sequence structure of a screenplay first introduced by Frank Daniels—to the structure of the roll out. The sequential release of various extensions which make up the project must create a clear and identifiable journey with each part of the story, regardless of the platform, feeding into the next in the same way the sequences of a film script build on each other to create rising tension. The idea has been well received among industry circles and I have already applied the concept to the projects I am producing.

“The Narratives of the world are numberless[…] Able to be carried by articulated language, spoken or written, fixed or moving images, gestures, and the ordered mixture of all these substances; narrative is present in myth, legend, fable, tale, novella, epic, history, tragedy, drama comedy, mime, painting […], stained glass windows, cinema, comics, news item, conversation”

The volatile state of storytelling provides a unique opportunity. Unfortunately, I feel that the University of Malta has been largely absent from this debate. While MIT and University of Southern California, to name just two, have recognised the importance of transmedia and its study, Malta is dragging its feet. This is not something new. Film has also suffered similarly, and has had to deal with the consequences of being sidelined for many years.

Malta can never become Hollywood and should never aspire to be such. However, as technology becomes cheaper, possibilities for creatives are on the rise. Digital creative work and critical media literacy play a defining role in our information society. Studies show that all aspects of contemporary life are being affected, including the way many professional visual artists ranging from multimedia performers to film-makers and publishers pursue their practice. Educational institutions need to start preparing students to face the realities of today’s landscapes.

MCAST and the University of Malta urgently need to create and develop programs that explain the new economies emerging from these technological shifts. At the moment this is not being done. Without a shadow of a doubt, I am certain that it will come back to haunt us.

Find out more:

-

Dowd, T., Niederman, M., Fry, M. and Steiff, J. (2013). Transmedia. Burnington, MA: Focal Press.

-

Hutcheon, L. (2006). A theory of adaptation. New York: Routledge.

-

Jenkins, H. (2008). Convergence culture. New York: New York University Press.

-

Rose, F. (2011). The art of immersion. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

-

Scolari, C. (2014). Transmedia archaeology. [Place of publication not identified]: Palgrave Pivot.

-

Wolf, M. (2012). Building Imaginary Worlds. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Comments are closed for this article!