Water is our number one resource. It not only sustains life, but also supports the economy and its development. And yet, water is taken for granted. Kirsty Callan talks to Marco Cremona, the man behind the revolutionary water treatment solution that promised to reduce Maltese hotels’ water use by 85%.

Malta is an island surrounded by sea. Malta is also almost a desert. It has less than 1,000m³ of water per inhabitant, the generally accepted limit to sustain agriculture and life.

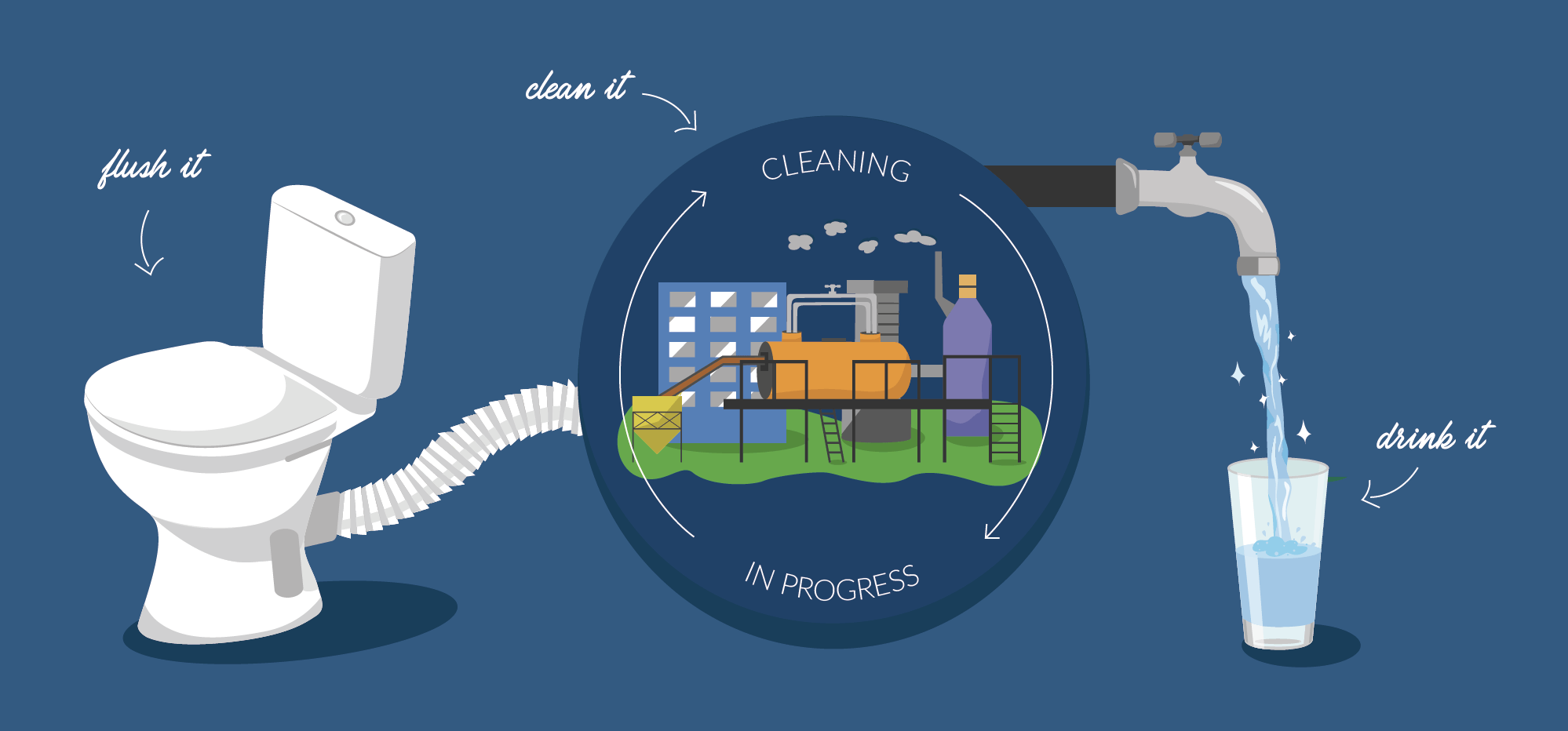

So why do we insist on using an immensely expensive process (reverse osmosis) to turn all the water we consume (an average of over 100 liters per day) into high-quality, potable drinking water when we only actually drink about two liters of it, at most?

This question baffled celebrated hydrologist Marco Cremona for a very long time. ‘We are making that extra effort to produce very good-quality water, which comes at a high cost since we don’t have very abundant water supplies, and people don’t drink it. Where is the sense in all of this?’ His contribution to the solution was the HOTER system, a membrane-based process that turns hotels’ waste water into water that matches the hotel’s water quality demands. The system can reduce the hotel’s reliance on external water by up to 85%. But quite recently, the Maltese Food Safety Commission denied him a licence over fears of unknown compounds that have not, as of yet, been discovered and cannot be tested as being present in the water.

BACKSTORY

Cremona’s career in water sprang up during his course in mechanical engineering at the University of Malta (UM). ‘I am now a water treatment engineer because of a fourth-year design project,’ he says. The project saw him designing a solar-powered reverse osmosis plant, an endeavour which required him to reach out to people in the water treatment industry. A different project could have led him down a different path, he admits, ‘things do happen by chance.’ However, what followed from there was a very deliberate set of decisions.

Following graduation, he went on to work with a local water treatment company, but an opportunity soon presented itself. In 1995, there was a one-ti me master’s at UM in hydrology—the study of water in all its aspects. He took the leap, quit his job, and jumped back into his studies.

This shift brought further changes. Cremona became an activist. This passion stemmed from being part of the team that carried out the first environmental impact assessment in Malta. Cremona started to volunteer with a number of NGOs, voicing his concerns about water and the islands’ environment.

With sewage being 99.9% pure water, why are we simply throwing it away?

‘Malta is a country with very limited resources, which means that we should be more diligent and more careful about how to make these resources last longer. You do that by being efficient, having long-term policies, recycling… a number of measures,’ Cremona states.

In 2002, ‘I took the plunge and started doing my own thing.’ And he hasn’t looked back. For the last 16 years, Cremona has been self-employed, using his water expertise and engineering background to provide consultancy, products, and equipment to anyone related to water, be that beverage companies, hotels, or government. In this time, he has also had stints working on development projects abroad, including Sri Lanka in 2005, following the devastating tsunami.

ALL OVER THE WORLD

The HOTER system began with an idea: What if a building or business could have its own water recycling treatment plant?

‘Whatever I dream, I can carry out a few calculations, then build something,’ Cremona says, alluding to how his engineering background came into play when working on this idea. Hotels proved to be the prime example, with Malta’s economy geared so much toward tourism and the hospitality industry. With sewage being 99.9% pure water, why are we simply throwing it away? ‘With each flush, we are eff ectively flushing away as much as 10 kilogrammes of quality drinking water, simply to transport a few grams of contaminants,’ Cremona laments.

With HOTER, the sewage is first converted into second-class water, which can be used to flush toilets and for gardening. The excess receives further treatment at a second plant, bringing it to drinking-quality level, primarily for use in showers. With this system, each drop of water can be used as many as 20 times before it leaves the system. Groundbreaking.

The HOTER project was applauded and embraced the world over.

It was featured on news channels all over the globe: BBC, France 24, Al Jazeera, and others. It was nominated for the 2010 Stockholm Water Prize, and ranked as one of the three finalists for the best green business idea in Europe in 2009’s prestigious CNBC/Allianz awards. Cremona was even awarded a Republic Day’s honour in December 2014 for his outstanding achievements in the water sector in Malta and internationally. Then, stumbling blocks.

In 2013, the Maltese Health Council stated that use of Marco’s recycled water was not permitted for human consumption. This was despite the fact that the system had been through several tests which proved the water produced by HOTER conformed to and even exceeded the standards of the EU Directive and Maltese laws.

The final blow came from the Food Safety Commission, which refused to grant the project a license. It stated concern about the possible presence of ‘pathogens and other chemicals that may have a harmful effect on human health,’ adding that current safety standards were insufficient. They also brought up the worry that the system could have ‘adverse effects on the tourism industry’ due to the risk involved in implementing such a system.

Can you drink sewage? The instinct would be no—but in the right place and with the right technology, you can.

Cremona says that the whole experience was disappointing. ‘Unfortunately, I have given up on the idea because I have been labouring to get a permit to use the water locally for more than seven years now. I think it is too advanced for its age,’ he states. But there is still hope. When asked if he sees a future for the HOTER system, Cremona still has faith in his work. But he believes it will not call Malta home. ‘It will happen,’ he says. ‘But I am now at an age where I can’t give up everything else and just follow this project. I’m willing to collaborate and not keep the idea to myself. I’d like to see it developed. I believe this is the way we will manage water in the future’.

Having been contacted by others who believe the idea has potential, it seems like only a matter of time before we see the system implemented somewhere in the world.

HOPE NEVER DIES

While the HOTER project may have an uncertain future, Cremona is still working hard to communicate the importance of sustainable development. He is currently working on a game designed to bring that message to children.

Developed in collaboration with Prof. Alexiei Dingli (Faculty of ICT, UM), the game takes users back to when Malta was first inhabited. The goal is to survive and increase the population whilst sustainably managing resources.

The idea for the game, which has already won the Malta Innovation Award despite still being in development, came from Cremona’s frustrations at repeating the same story over and over without receiving enough attention. ‘I thought it would help if I created something visual, if I could help them imagine a Malta in which they made the right decisions,’ he says.

Motivated by his strong sense of fairness above anything else, Cremona says, ‘I think that what we are doing today is quite unfair on future generations. We are using water reserves that have accumulated over centuries as if there is no tomorrow. It has to change.’ Cremona recounts, ‘I remember in my teens there wasn’t enough water in the country,’ speaking of times when tap water was only available on certain days of the week and water even had to be shipped in from Sicily.

‘While I can fully appreciate the benefits of reverse osmosis technology, strategically it is very dangerous to put all our eggs in one basket,’ says Cremona. This is why he continually advocates for the safeguarding of groundwater, Malta’s only substantial freshwater resource.

While water consumption is not as sexy as saving turtles, it needs people’s attention. And it needs it now. ‘Pumping too much water is helping to grow fresh produce in summer. But it’s crazy to try and grow anything in the Maltese summer when the value of the water is more than that of the product. But it would upset people if I was to suggest restrictions’.

Our conversation ends with a call to action for all the young people out there. Cremona asks them to be active. ‘First observe, then question, and if you aren’t satisfied with the reply, then try to do something about it.’ Using his own example, he makes the point that there is no such thing as a stupid question. ‘Can you drink sewage? The instinct would be no—but in the right place and with the right technology, you can.’

Change is within our grasp.

HOTER project was developed in partnership with SUSTech Consulting, Island Hotels Group, ttz Bremerhaven, the Government of Malta Department of Public Health and the MCST Research & Innovation Programme 2006.

Author: Kirsty Callan

Comments are closed for this article!