When we study history, we might think of larger-than-life figures such as William the Conqueror and Napoleon or of crucial dates such as the French Revolution of 1789 or the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But it is also possible to look at history through the lens of microhistory and socio-economic processes, focusing on the daily lives of the people or communities that lived through the time. For the team behind the project Playing Maltese History, this lens was the starting point for their video game, ‘Valletta: Streets of History’.

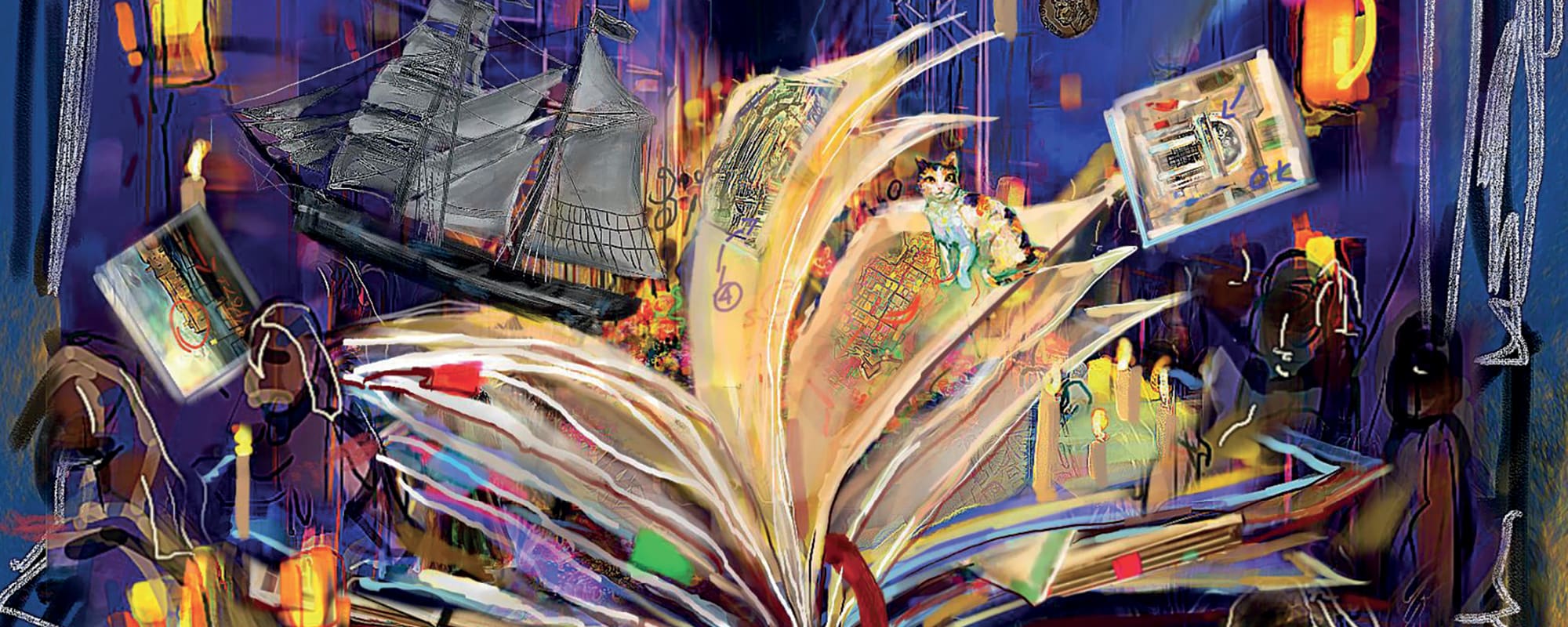

Your adventure begins at the National Library of Malta (Bibliotheca), just behind St John’s Co-Cathedral. Within its neoclassical, limestone walls lie volumes of scholarly texts and newspaper archives, each clipping providing insights into historical life in Valletta. With your trusty notebook in hand, you have a clue to your next destination…

Valletta: Streets of History puts you in the role of a historian/ detective as you piece together stories inspired by historical and archived works. The mobile supported treasure hunt invites you to explore various locations in Valletta, trying to uncover clues and solving riddles as you connect the dots to resolve a mystery.

Valletta: Streets of History is a location-based augmented reality (AR) mobile game developed by academics and alumni from the Institute of Digital Games (IDG) and the Department of English at the University of Malta (UM). Dr Renata Ntelia, the project leader behind Valletta: Streets of History and a Ph.D. graduate of the IDG, explains to us, ‘Think of Pokemon Go. That covers the mechanics of the approach, in the sense that it invites the user to go from location to location and interact with certain texts or AR elements. However, the main difference is that, in our case, we’ve gone for a historical setting and story.’

The game itself consists of three stories, each taken directly from archival research. Drawing from Valletta’s rich history, the team wanted to focus ‘on the parts of history that aren’t so well-known,’ explains writer and lead researcher Dr Krista Bonello Rutter Giappone, visiting senior lecturer with the Department of English and research support officer with the Centre for Labour Studies. ‘The game centres on marginalised voices from the past.’ For example, one of the stories tackles the bubonic plague outbreak of 1813. Another, written by Department of English alumna Ms Naomi Cutajar, follows the story of a young Jewish woman growing up in early 20th century Valletta. However, the game itself has the ability to incorporate a multitude of stories. ‘The game itself is very modular. You can play the stories in any order, and it would be very easy to add more stories later on in the future,’ explains writer and researcher Dr Daniel Vella, senior lecturer with the IDG.

But how does one go about creating such a game?

It starts with research…

…and lots of it! ‘We started with archival work,’ says Bonello Rutter Giappone. ‘The Bibliotheca was just one of the places we visited, but we also went to the archives at Santo Spirito, and the National Archives in Mdina. We also had recourse to private collections such as that of [Judge Emeritus] Giovanni Bonello, as well as consulting people from the Notarial Archives.’ While the team started off with an idea in mind, the discovery of new texts in the archives, along with consulting secondary sources, helped to direct them to certain cases. But despite Valletta’s rich history, it was important for the team to identify a focus for the game.

‘We made a choice early on that the focus should be on the 19th century going on to the early 20th century,’ explains Vella. ‘Firstly, there’s a practical reason: the availability of archives. With the 19th century, there is a lot of archival material to draw from.’ The second reason was language. Archives from earlier time periods were often written in Latin, whilst records from the 19th and 20th century were written in Italian and English. This made the process of poring through documents slightly easier for the researchers.

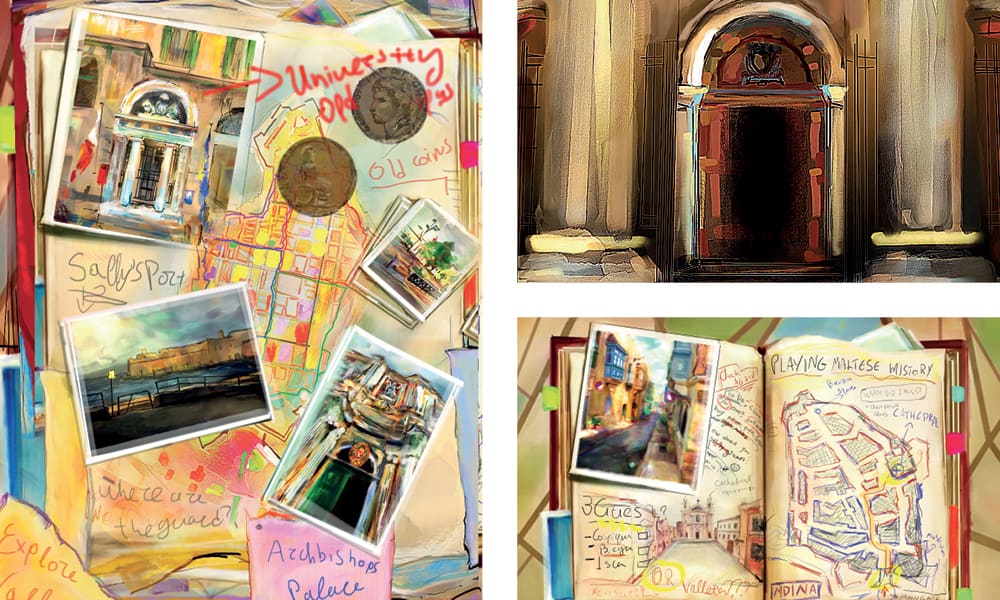

While the stories focus on the historical individuals, the real star is the city of Valletta. ‘For me, the city itself is the protagonist,’ says Ms Aphrodite Andreou, the game’s artist. The game presents clues to the player through a journal. ‘I wanted the art in the journal to look like fast, quick sketches to give the game a tactile aesthetic. For example, a sketch of what a particular building looks like now, but without contemporary aspects that could break a player’s immersion. However, it was important that the buildings are still recognisable to the player.’ Besides the main journal entries, there are also different, smaller images to help illustrate the game’s interface, as well as AR models of buildings that don’t exist anymore, such as the original main gate of Valletta.

Telling us about her creative process, Andreou explains how, ‘every team had their own specific process that they used to follow. For me, after learning about the story and taking the feelings we wanted to convey, I explored how each place looked. Using photographs other people took, seeing different angles from Google Maps, for example, and visiting certain locations before deciding how to portray each one.’ For the team’s programmers, Ms Emmanuela Marla and Mr Yannis Brellas, the focus instead was on the technical mastery of the game system; accommodating for the designers’ creativity while balancing out technical integrity for an error-free end build is no easy task. The game incorporates many different elements that need to be finely tuned for a smooth gameplay experience, particularly when exploring real space in real-time.

Gameplay Elements

It will take the player more than visiting key locations in Valletta to crack the case, though! There are a number of riddles the player will need to solve, before a clue to the next location is revealed. ‘We have a number of riddles and puzzles,’ explains Ntelia. ‘For example, during one of the stories, the player needs to work through a logic puzzle, reminiscent of games such as Return of the Obra Dinn’ – as particularly keen super-sleuths might notice. ‘The game provides names, addresses, and symptoms (all taken from actual newspapers of the time), and the player needs to figure out who the first victim was.’

Other mini-games are optional. The variety of mini-games creates an element of replayability. ‘Each mini-game would represent a unique challenge that would relate to a specific location,’ explains Vella.

The stories selected, design elements, and AR elements all come together to help the player reimagine Valletta. ‘Personally, one of my interests is space and place in games,’ Vella says. ‘I wanted the game to look at the space a bit differently. If you’re Maltese, or even if you’re a visiting tourist, you’re used to seeing Valletta in one way. But the game can turn that city space into something different and even generate new meanings to it.’ Certain games set in historical settings, such as Assassin’s Creed and Kingdom Come: Deliverance, allow players to reimagine modern locations as they might have appeared in the past. They help us, as players, cultivate a better understanding of the past.

Building upon this point, Bonello Rutter Giappone refers to psychogeography. Essentially, this idea of urban exploration took form in the 50s and 60s in response to the effect of urban geography on the emotions and behaviour of individuals. ‘We have certain frames of perception that are formed out of habit. We almost become desensitised as we follow the same route every day. But by exploring different ways of viewing a space, we can break or bend that habit.’

For Ntelia, it is the historical mystery that makes the project exciting. ‘It’s about how people lived in this space. We wanted to focus on the parts of history that haven’t been exposed yet. So it’s not just uncovering new locations in the past, but also experiencing the history of marginalised groups.’

Playing History

‘When I was taught Maltese History, it was simply a list of Grandmasters and important dates. We really wanted to look at things that aren’t normally part of the historical narrative,’ explains Vella. As an educational tool, the game has the potential to foster a love of history. It might inspire players, young and old alike, to find out more about the history that surrounds us.

Bonello Rutter Giappone takes this a step further, ‘We’re trying to give the player the experience of archival discovery, giving the player some agency in the practice of being a historian. For example, rather than simply presenting history through our writing, we give the player the option to look at the actual manuscripts found in the archives and private collections.’

While games can potentially be used as educational tools, ultimately the true test of a game is how fun it is! If you’ve always wanted to be a detective or have a penchant for solving riddles, Valletta: Streets of History should be right up your alley! Try the game for yourself through either GooglePlay or the Appstore.

The team would like to thank Arts Council Malta, Judge Emeritus Dr Giovanni Bonello, Dr Joan Abela, Mr Noel D’Anastas, Mr Louis Cini, Mr Vince Peresso, the National Archives and Santo Spirito staff, Ms Chanelle Briffa, Dr Sarah Azzopardi-Ljubibratic, Mr Gabriel Farrugia, Dr Evelyn Pullicino, Professor Yosanne Vella, and Aline P’Nina Tayar.

This project is supported by Arts Council Malta.

Comments are closed for this article!