‘If you are a woman working in a traditionally male hierarchy, you have one of two choices: Quit or Masculinize’. Linguist Prof. Lydia Sciriha chose to end her keynote speech at the HUMS symposium with this quote from Pease and Pease (1999). As a curious scientist and keen observer of society, she has accumulated a plethora of personal stories to show how communication gaps solidify gender inequality. She shares them here with Daiva Repeckaite.

In 2019, female graduates by far outnumbered males. This was not the case when Prof. Lydia Sciriha (Department of English, University of Malta) started her own academic journey. Then, women made up under a third of undergraduates, and graduating female PhDs were counted in single digits. Four decades later, over half of new PhDs and lecturers are women, but their share shrinks as they move up the academic ladder.

Even though female graduates outnumber males, men still dominate in decision-making roles. In her talk, Sciriha presented data over a span of forty years to show that Maltese women have now cracked the glass ceiling. Yet her sociolinguistic research shows that for women to succeed they must change their communicative styles. ‘We are not competitive and we are not hierarchical, because we are socialised differently,’ Sciriha adds, noting that women prefer to use the first person plural instead of the first person singular as a way to include others. She admits that she herself has a tendency to say, for example, ‘We convened a conference,’ which gives the impression that she had a huge team of people to help her out, which was not the case. ‘I now say – “last year, I convened a conference”, but it is still very difficult to learn to adjust such habits. When women speak, they try to downplay their achievements,’ the linguist says.

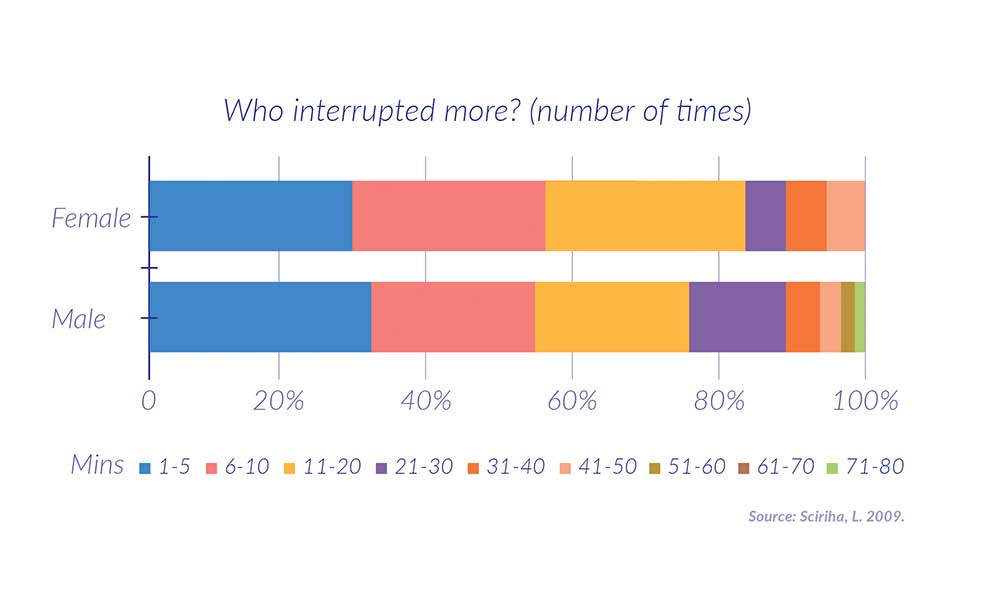

‘But when you want to be heard, at times you just cannot wait for your turn to speak. You have to learn to interrupt like men do. The power dynamic is a key factor. As a woman, I’ve learnt that if men interrupt, so should I!’ she explains, and brings in data to prove this point. In a study published in 2009, Sciriha and her team recorded 108 minimally-guided interviews with married couples and later transcribed them to study men’s and women’s speech patterns. These interviews lasted half an hour on average (some were longer), but nearly a quarter of the men interviewed managed to interrupt their wives more than 20 times (see in graph above).

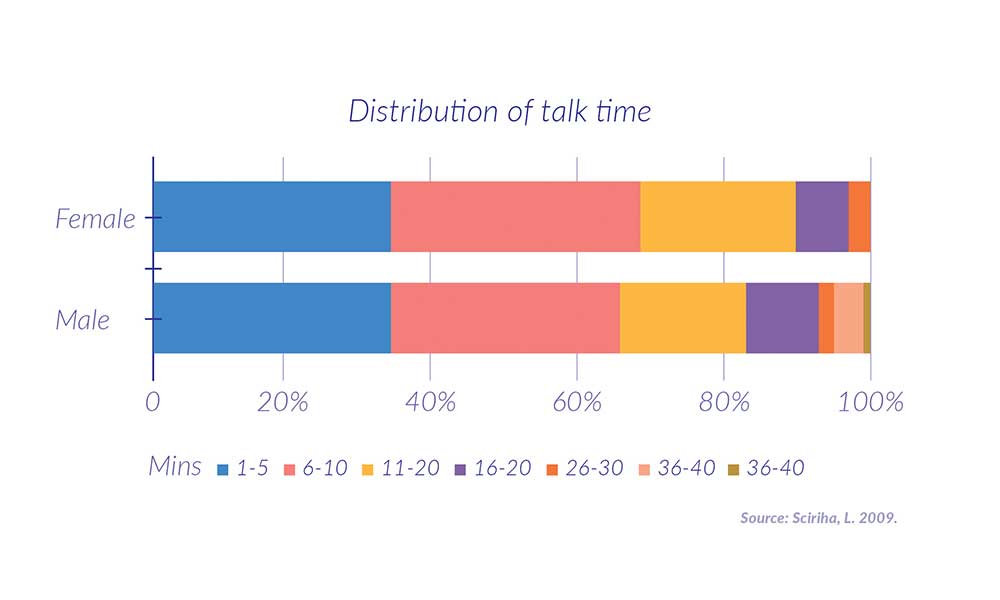

For Sciriha, communication around her is a never-ending source of inspiration. Her current research revolves around linguistic landscapes, taking note of the diverse languages used in street signs, plaques, warnings and instructions, and house names. Communication at conference talks and lectures, as well as meetings with the students she supervises give her ideas for research pointers in gender and language. ‘There have been times when I have had around 100 students attending my study-unit on English in Society. One of the topics I lecture on focuses on language and gender, and I introduce this topic by asking my students, “Are there differences in the speech of men and women?” And invariably the first difference students cite is, “Women are always talking”.’ Do they? Employing her students to collect data, Sciriha mapped how talk time is shared in married couples (see in graph below).

The academic environment gave her many more examples of how gender structures the way individuals interact. After finishing her PhD in linguistics in Canada, Sciriha joined the university in 1987, and female academics in the Faculty of Arts were conspicuous by their absence. ‘I had another disadvantage – I was still very young. I was a greenhorn. I did not have experience,’ she remembers, and it did not help when she faced a barrage of microaggressions. Despite her quick rise to the post of Director of the University’s Language Laboratory Complex (a language laboratory with a sound library), strangers still took her for a secretary.

Science ended up shaping her way of communicating. ‘Sociolinguistics has taught me so much and has opened up my horizons!’ says Sciriha, who learnt the hard way how to be direct and assertive. ‘I’ve been teaching language and gender for the past 32 years. One of the most eye-opening books has been ‘Women don’t ask’ by Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever who cite several studies to show that women are afraid of asking, for example, for a raise in salary, unlike men. What they’re afraid of is a no. Prefacing my requests with a polite “Would you mind?” does not get me anywhere with some people. So I have learnt to be direct and assertive and say, “I need it, please endorse my request!” It is certainly not easy to undergo such a change in communication style, but there’s a limit to how much I can put up with,’ she says, before adding one more example to show how being adamant is key to achieving desired results.

‘Some years ago I needed a new computer as my old desktop had broken down. One of the IT specialists, who knew how important it was for me to have a new computer specifically tailored to my needs, guided me as regards the specifications of the computer I required. When I went with my request to the person who would procure my computer, his initial reaction was that the computer I had asked for was expensive. I justified my request by emphasising that I use different software applications and that I don’t just use my computer as a word processor. Moreover, I also named the IT services specialist who had instructed me to ask for that particular computer. Of course, I got the computer I had asked for. My request was clear, direct, and I had also backed it up by citing the IT specialist as the authority on the subject.’

Even today, some colleagues feel they can boss her around. ‘I’ve got many stories like this – I wish I could write a book about it,’ the linguistics professor smiles, looking at a shelf full of books with her life-inspired chapters. Over the decades, she has perfected her strategies for standing her ground. ‘But is it fair that I have had to change my way of communicating? It seems I had no choice.’

Further reading:

Sciriha, L. (2009). Different Genders, Different Communication Styles? Patterns of Interaction Between Maltese Couples in Malta. In S. Borg Barthet (Ed.). A Sea for Encounters: Essays Towards a Postcolonial Commonwealth (pp. 365-378). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Comments are closed for this article!