Virtual Reality (VR) has created a whole new realm of experiences. By placing people into varied situations and environments, VR enables them not only to explore, but to challenge themselves and gain skills in ways never thought possible. With applications in medical and psychological treatment, VR is now being used to train surgeons, treat PTSD, and to help people understand what it’s like to be on the autism spectrum. The key to this application is VR’s ability to immerse its users.

Many agree that immersion needs two key ingredients: a sense of presence and interaction with the environment. Interaction comes in three main forms. Selection is about differentiating between items in the environment. Navigation allows travelling from one point to another and observing the environment. Finally, manipulation lets users grab, move and rotate selectable items. In addition to this, VR applications need a setting. Supervised by Dr Vanessa Camilleri and Prof. Alexiei Dingli, I chose to use escape rooms (adventure games where multiple puzzles are solved to leave a room) to experiment with these interaction techniques.

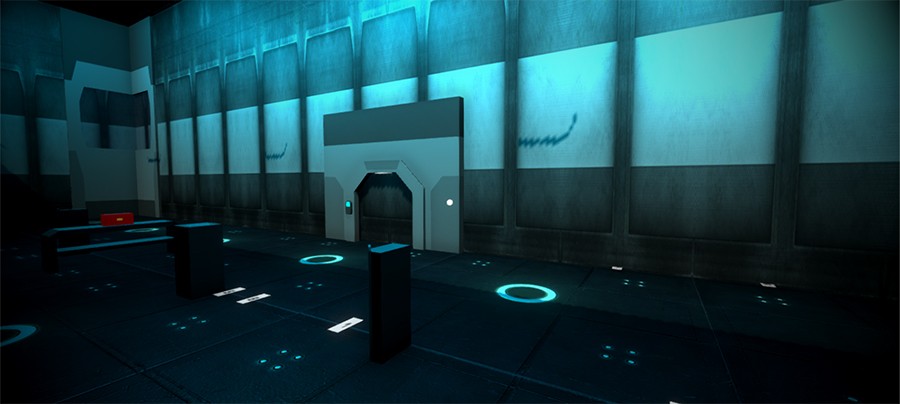

I used escape rooms because they’re highly interactive and naturally immersive systems. And since interaction isn’t a one-size-fits-all scenario, I also applied procedural content generation (PCG) techniques to create the escape rooms themselves.

People selected items using a reticle, a small circle in the middle of the screen which expands or contracts to indicate which objects they could interact with. They navigated the space by looking around through the VR headset and moving their joystick. They manipulated puzzles from a separate screen which I layered on top of the escape room. This allowed them to inspect objects to their heart’s content, while also reducing the amount of clutter in the room.

Since there was no previous work in PCG escape rooms, I had to pave my own way. I used a genetic algorithm, a machine learning algorithm that mimics evolution in biology to select the best solution to a problem, to determine which puzzles and items would be placed in the escape room. I also programmed the game to create the rest of the room, placing floors, ceilings, and everything else that the algorithm didn’t consider. This made the space look like it had been made by an actual person, despite being created through AI.

From the results gathered, most people found that the system allowed them to explore the VR environment in a very natural way. Players said that the room’s generated interaction was consistent, reliable, and fun.

Understanding immersion is critical for VR’s future applications. If we can help people hone these techniques by creating a few games along the way—so be it!

This research was carried out as part of a Bachelor of Artificial Intelligence at the Faculty of ICT, University of Malta

Author: Natalia Mallia

Comments are closed for this article!