For such a tiny nation, isolated on the periphery of many gargantuan nations and empires, the Maltese share an eventful and varied history. Dr Charles Xuereb, in his new book Decolonising the Maltese Mind: In Search of Identity, gives a fascinating account of the Maltese existence and how different peoples passing through the island nation have affected its culture across history.

Dr Charles Xuereb has spent his life unfolding the creases of Maltese history under a magnifying glass. His latest book is a heavy read that is best savoured as a marathon. The reader may wish to keep the copy in an easy-to-reach location to ensure that they can pick it up at any time and repeatedly return to the text, part by part, chapter by chapter. Two main reasons make the reading process challenging.

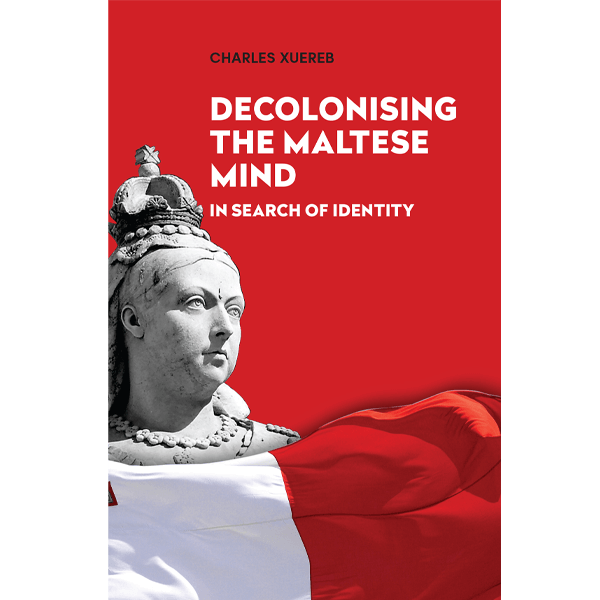

Image courtesy of Charles Xuereb

Firstly, despite looking like a book, the edition reads like a well-founded research paper: a must for any good academic text, which will pose an arduous task for the everyday reader to get through. However, for anyone willing to make the effort, the rewards are soon reaped. The overview itself, which is based on a staggering 870-item bibliography, offers thought-provoking insights that can spark great, long-lasting dialogue, potentially shaping the thinking of generations.

Secondly, the premise Xuereb raises, taken at face value, may be hard to digest – for some, it may even be outright outrageous. The foundation of the book rests on the claim that the Maltese mind must go through a decolonisation process after almost two centuries of British indoctrination to ensure that true Maltese identity, free from any historic-cultural indentations, can emerge for the benefit of the nation. Such a double- edged argument is courageous. Today, public dialogue is globally infested by a high degree of polarisation. When we try to defend our views, we increasingly fall victim to attacking self- and foreign-made strawmen, the most common cognitive biases. Conversely, Xuereb advocates leaving this binary thinking behind and appeals to us to summon our most humble intentions and engage in conversation to find solutions, abandoning the urge to defend our own precious opinions against all odds.

The author, quite possibly aware of these points, offers a strong compass hidden in the heart of the front cover flap. ‘The strong arguments and facts about British colonisation found in this book, however, should be read and digested without subjective bias. They address not the British people and their friendly historical association with the Maltese – several are even blood relations – but the machinations of what was called the Colonial Office in the metropole that had orchestrated uncivil – often undemocratic, sometimes criminal – ploys, to subordinate peoples to the despotic rule of British political authorities.’

Whether the reader agrees with Xuereb’s opinion about the Colonial Office, the essence hidden between these lines is vital. As we revisit our history – cognisant of the fact that the victors usually pen it – we must remember that condemning past nations for their evil actions hardly benefits our present or future. On the contrary, becoming aware of the darkest hours of history can help us learn from our ancestors’ mistakes and guide us in leading a better present. It allows us to write a more constructive history, so long as we are in power and at the peak of our mental capacity. Nothing is more important than that. ‘History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme,’ says the adage by Mark Twain. Xuereb’s book helps its readers review Malta’s history and hopefully equip themselves to call out when familiar rhymes may emerge from the incumbent singing powers.

A Roadmap Through History

In search of identity, Xuereb has reviewed an intense history through a well-structured roadmap. The eight chapters create a logical arc for the reader to tread through a rich text with over a hundred historical illustrations.

The book starts by giving a historical overview of empires and related activities, briefly glimpsing into the Phoenicians, Romans, Carthaginians, Aghlabids, Arabs, Christian Crusades, Normans, Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, South Americans, Russians, Indians, and Chinese. Then, the text arrives at modern colonists and discusses what Xuereb calls ‘colonial apologies’.

Next, the work overviews how Malta became a British colony before discussing what Xuereb brands as a ‘struggle for Maltese identity’ under British rule. He argues that the Maltese were ‘bombarded with imperial propaganda’ as colonisers worked to ‘construct an identity dependable on a superior authority’, which was burnt into colonial memory, complemented by reinforcing such an identity post-WWII.

Treading on, the author discusses the role played by the English language, often prioritised over Maltese, in shaping the local identity. ‘Perhaps it is time for the University of Malta to consider the introduction of an apposite course in Maltese public speaking and communication,’ Xuereb writes. He also addresses 2021 NSO statistics that say 97% of respondents consider Maltese their first language, and 75% claim to speak Maltese to their children. However, students are often seen speaking English, and the younger generation is more likely to consume content in English – so the author argues.

After Independence in 1964, Maltese society remained influenced by the Catholic Church and infatuated with British colonial artefacts, including the obsolete English phone boxes, combining both influences in this shot in Merchants Street, Valletta.

St John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta, recognised by Tripadvisor as the overall ‘Travellers’ Choice Best of the Best 2022’ award winner and one of the Top 25 Attractions in Europe. Pity tourist visitors have to enter through an entrance in Republic Street – flanked by the bust of its benefactor Pope Pius V and the national Great Siege monument yet marred by a cluttered sight of commercial paraphernalia, including two useless telephone kiosks, states the author in his book. This European heritage certainly deserves better. Photos by Charles Xuereb

In the book’s second half, the author showcases monuments of colonial propaganda across the island and how artefacts of Maltese memory were erected after Malta gained independence and joined the British Commonwealth in 1964. He takes the reader on a journey of British colonisation statues worldwide, even mentioning recent instances of such monuments being brought down. After mentioning Maltese anticolonial outbursts, the book discusses the modern emergence of culture wars and individualism. In the last chapter, Xuereb discusses how the triad of tourism, identity, and colonial legacy continues to affect each other today.

Forging a New Identity

The freak COVID-19 pandemic has caused so much grief and yet has sparked many improvements and beneficial novelties across the globe. This book undoubtedly falls in the latter category. Xuereb started working on the book during the pandemic- imposed lockdown and filled the tome with an abundance of ideas that will hopefully get people to talk. The more civil and open the conversation, the better it will be in the long term for us, living on this beautiful island.

At the very end of the book, Xuereb contemplates the extensive research he has done – the very legwork that has been boiled down into an essence in the form of a concise, well-researched publication. ‘One almost wonders if the Maltese are the greatest absorbers of the world […]’ the author ponders, taking stock of the tiny nation’s many influences, floating on an endless sea tucked between two massive continents, so close and yet so far.

The writer inquires whether a Maltese national can dive into the depth of such a varied historic-cultural mix and ‘find an own identity that encompasses all their past’ without being biased by the many nations etching their own flavours onto the rocks of the island.

Your columnist, who has found a new home on this magnificent island, wonders whether his own nation could do the very same. Could the pagan nomads, who took centuries to wander from the Ural Mountains through the Middle-Volga region and the Eastern European steppe chasing a Miraculous Hind into the Carpathian Basin to settle for good and convert to Christianity, ever rally to forge their own identity? The challenge is ever present for us to realise that we can honour and preserve our national legacy even as we mingle – at home and abroad – with new cultures in our globalised world. We must leave doors open for change; that is the only way for us to evolve.

And for this very columnist, it is even more challenging to remain unbiased, given Xuereb’s approach to his closing thought: ‘Education shall be the very vehicle to help us humans find our true identities in the long term so we can live contently, together, even if sharing differing identities. The time has come for the world to realise that educational systems need an urgent upgrade, and we must take action today. Even if it may impact votes on the ballots for incumbent governments. Even if later governments may reap the benefits in voters’ eyes. Conversely, we must act today for that very reason: improving our education system is slow; some may argue we are already too late.’

Xuereb’s book pinches a nerve, and we must bear it. That is the only way to ensure we can spark a beneficial public dialogue for future generations.

Author

-

Christian Keszthelyi is an English linguist-turned journalist, writer, PR flack–you name it. He contemplates a lot about life and writes every now and then.

View all posts

Comments are closed for this article!