It all started with half a thousand books donated to the UM Library in 2018. Then, six years later, your columnist attended an event called Friday Talks, organised by Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti (FPM), the guardians of Victor Pasmore’s legacy. And like that, you, dear reader, and I – together, we fall into the rabbit hole of abstract art. From order to chaos. Down, down, down. ‘“I wonder how many miles I’ve fallen by this time?” she said aloud. “I must be getting somewhere near the centre of the earth.”’

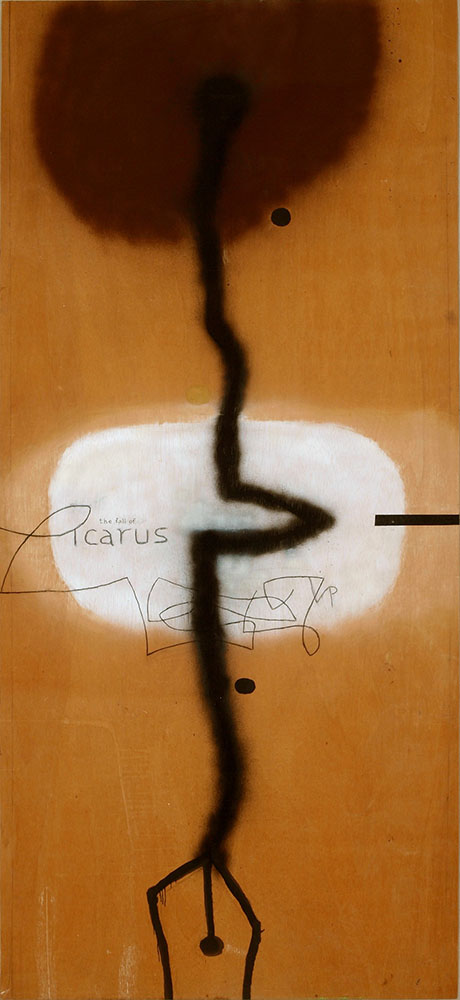

A backdrop of a wooden sheet. A brown circle. A black squiggly line pierces through the white fog. No. Not fog: Cloud. That is how Icarus did fall ‘to the ground from which you sprung’.

On September 2018, the UM Library came into the honour of receiving almost 500 books once owned by British artist Victor Pasmore. Certainly, curiosity comes to mind when we consider the UM Library received Pasmore’s books 110 years after his birth and 20 years after his passing.

The books reflect the life of their user. Pasmore’s presence breathes through the well-thumbed pages, pencil lines across the text, and unorthodox uses of bookmarks: a postcard, a letter, an exhibition invitation. The observer may stumble upon more here. Pasmore would cut out images from magazines and newspapers. Flipping through his books, now at the UM Library, the skimmer cum philosopher will find the scattered mind-crumblets of a genius among the sheets. Turning the pages brings Pasmore closer. And closer…

We are barely down a fortnight in 1908 when Henri Farman wins the Grand Prix d’Aviation – the first person to fly an observed circuit of more than one kilometre. As spring ends, the first American horror movie – a silent film – Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde premieres in Chicago. By the end of summer, Henry Ford himself drives the first Model T to Wisconsin and northern Michigan. On 3 December, a baby cries in a hospital. Edwin John Victor Pasmore is born.

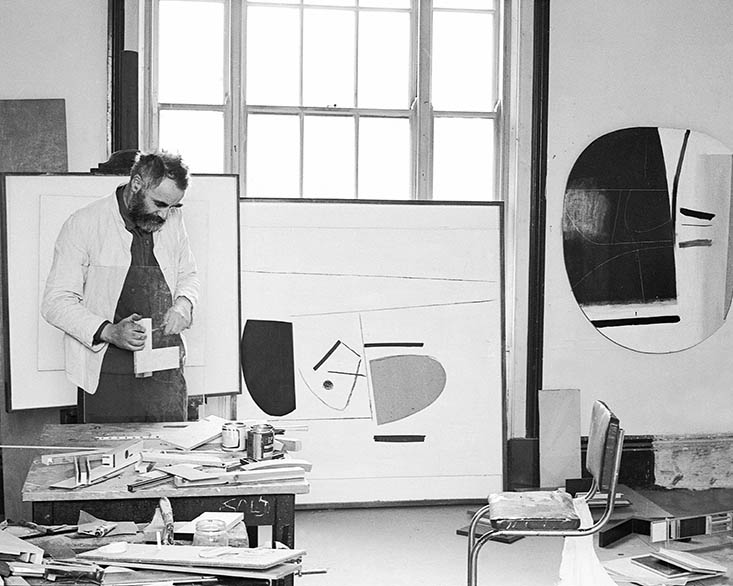

(Photo credit: Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti)

Giants. Eloquent figures. Monet and Cézanne influenced the young adult Pasmore in his figurative years. His art reflects our world to the tiniest details. But Pasmore becomes obsessed with nature, and he embraces it as a keen observer. In itself, this is somewhat ironic as he says that the trick is not to become enslaved by what the artist sees. As if a modern Stoic, the reincarnation of Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, Pasmore of Chelsam thus spoke: Nature operates according to rational and universal laws. Humans shall align themselves with this divine order. Oh, Epictetus, control your thoughts and emotions and let the Logos be.

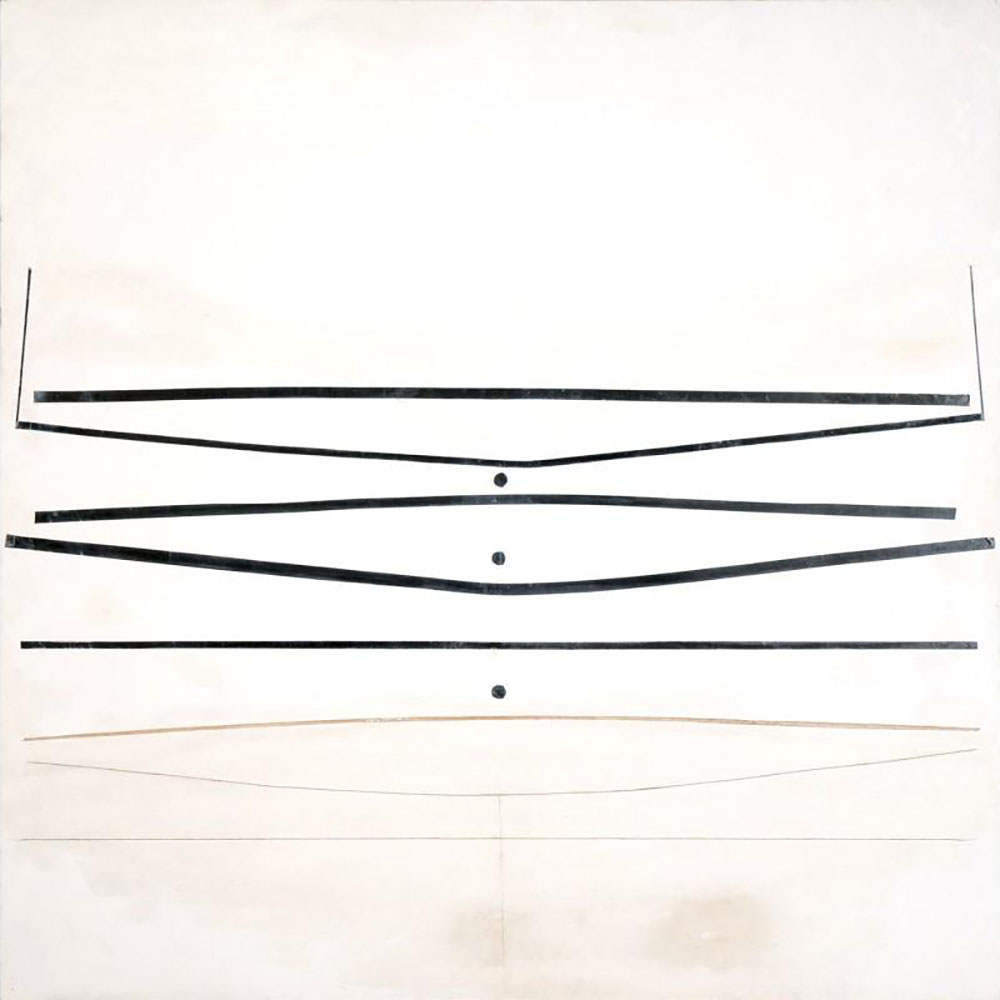

(Photo credit: Lisa Attard)

The world is white. Black lines – straight and bent. Three black dots. Evaporating lines – fading into the supermassive void of fleeting memory.

During the world wars, something broke for Pasmore and for humanity, too. In the Second World War, he refused to perform military service. He is court-martialled and sentenced to 123 days of imprisonment. One. Two. Three. One hundred and twenty-three days. He never served his sentence – the Appellate Tribunal in Edinburgh granted him unconditional exemption from military service.

With the war in his mind and heart, Pasmore meets the output of Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee. Pasmore develops a purely abstract style inspired by Ben Nicholson. Pasmore pioneers the use of new materials and occasionally creates on large architectural scales.

He supports painter Richard Hamilton; collaborates with architect-designer Ernő Goldfinger and sculptor Helen Phillips. He synthesises art with architecture. He represents Britain at the 1961 Venice Biennale, and soon he relocates. Victor Pasmore and Wendy née Blood, in wedlock and in a ménage à trois with art, move to Malta in 1966. The outskirts of the sleepy village of Gudja nurtures the typical Maltese farmhouse ‘Dar Ġamri’ – their home. The house and the garden become an extension of Pasmore, his personality and his art.

He arrived in Malta in turbulent times: The tiny island of the Mediterranean gained independence from the British on 21 September 1964; however, the State of Malta retained Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta and thus head of state. A decade passed. On 13 December 1974, Dom Mintoff’s Labour Party bagged the general election. All hail: The Republic of Malta. A handful of years later, a defence agreement expired on 31 March 1979. The British closed the last base and handed over their remaining lands on the archipelago to the Maltese government.

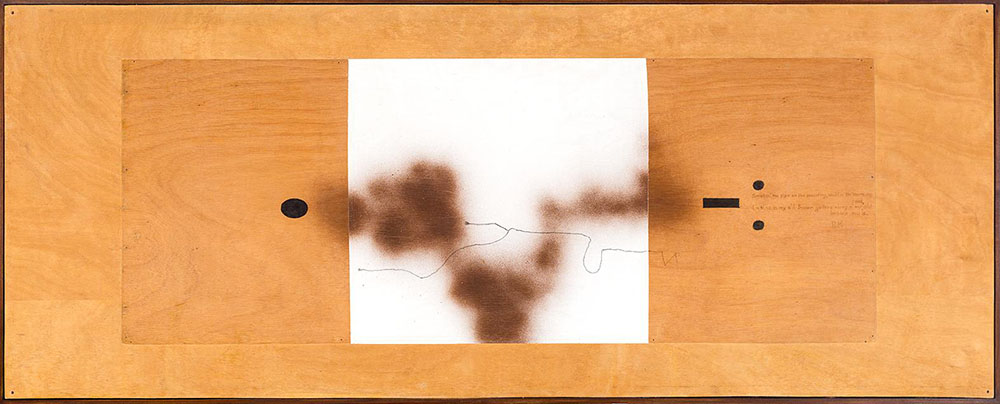

(Photo credit: Lisa Attard)

Wooden, white, bark. From the black dot to the black dash leads the slithering, earthy path of fumes. ‘Smokin’ my pipe…’ – RK

Malta leaves its mark on Pasmore. He can never abandon the effects of nature and his surroundings. The way nature operates and architectural heritage remain at the core of his creations. The similarity between the engraved lines in Pasmore’s work and those etched into prehistoric figurines is undeniable. Pasmore admits that his Maltese experiences bring him close to a Neolithic past, drawing on the great megaliths.

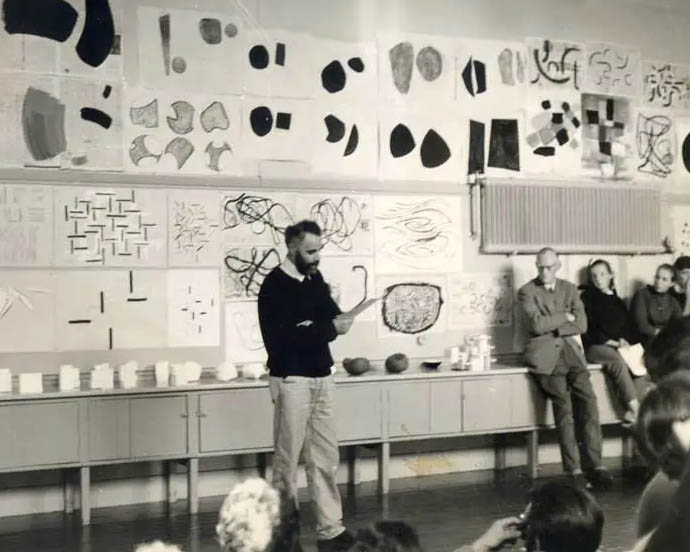

Pasmore’s presence leaves its mark on Malta. He mingles with his contemporaries; he learns from them and, at the same time, teaches his colleagues. Emvin Cremona. Alfred Chircop. Antoine Camilleri. Jean Busuttil Zaleski. Gabriel Caruana. Willie Apap. Harry Alden. Esprit Barthet. Carmelo Mangion. Because great things happen when people share ideas, the collective growth of knowledge happens when minds build upon each other’s work. As Isaac Newton said: ‘If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.’

In his later years, Pasmore would say he wanted to compose his artwork as if it were music. He said music has essential elements – sounds – and as they come together, they create symphonies and harmonies.

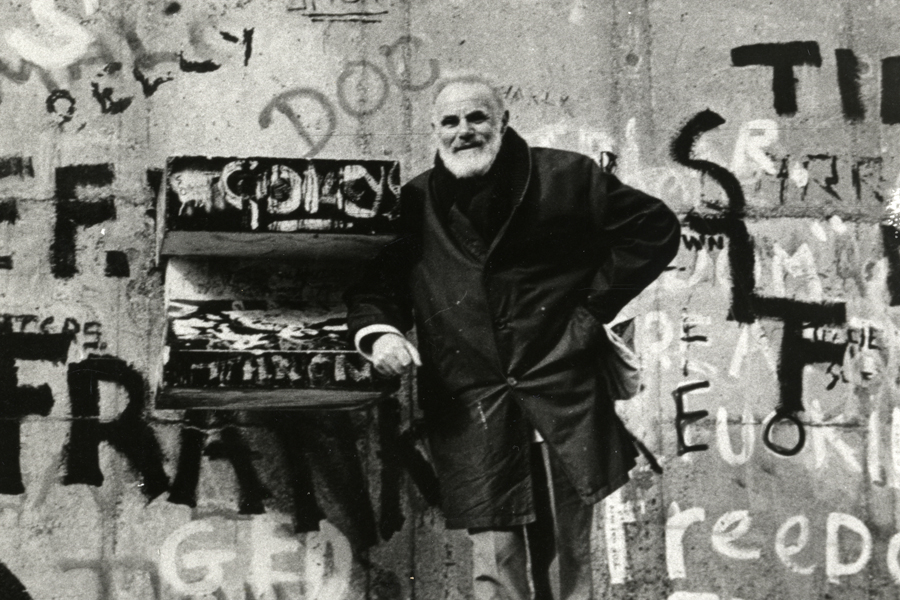

(Photo credit: Harry and Elma Thubron Archives)

(Photo credit: Marlborough Fine Art, London)

In November, Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti (FPM) hosted Tina Camilleri from Electronic Music Malta as part of their recurring art events called Friday Talks Series. Camilleri presented a live musical demo sitting on the floor behind a mixing console hooked up to a laptop with a luminous apple someone took a bite out of. In the dim light, the room filled with engaging sonically selected works for half an hour. Dogs barked. Sirens wailed. Then drums beat, and people nodded to the familiar bars in relief. And then, it peaked as fragments of a speech introduced language. Chaos ensued into order. Sitting in the embrace of Pasmore’s artworks, the artist and her audience talked. They discussed the process of exploring the interaction between sound and art.

Today, the FPM hosts the Victor Pasmore Gallery in Valletta’s St Paul Street. The gallery showcases a diverse collection of the artist’s works, reflecting his evolution and connection to Malta since 1966, alongside temporary exhibitions inspired by his legacy. FPM moved the gallery from the Central Bank of Malta to its standalone location in 2023, where it continues to promote and explore Pasmore’s contributions to art, architecture, and culture.

Every line, every nail, every spray splodge, every wooden block glued to a painting is the ordered chaos of expressionism. It is this abstraction that Victor Pasmore sparked into existence – the art that keeps him alive.

Comments are closed for this article!