As the ‘no waste’ movement becomes a trend and a force for good, Margaret Camilleri Fenech turns the magnifying glass on Malta to assess the local scenario.

The topic of waste is not much loved. In the early 2000s the problem became clear in Malta when the term ‘mini Magħtab’ was local slang for any pile of rubbish. At the same time the authorities realised Magħtab could not grow any higher. Malta’s ‘mountain’ had literally reached its peak.

The hype, backed by extensive EU legislation, led to the decommissioning of the Magħtab landrise in 2004, together with the erection of an entrance gate, the establishment of a disposal fee, and a statistical database that tracked waste production. We also saw various facilities introduced, including civic amenity and bring-in sites.

Man-made waste generation has exploded in the last 30 years, having an unprecedented impact. A major problem is one-way products like milk and fruit juice in Tetra-Pak bottles, disposable shaving blades, and countless other non-durable items that, years after they are disposed of, can still be found in our landfills. For Malta, this presents a challenge with no straightforward solutions.

Littering spoils both the countryside and sea shores, while waste treatment is land intensive, creating conflict. Finding suitable locations for waste treatment facilities is a major headache, often digging up deeply-rooted political divides and a sense of indignation related to ‘not in my backyard’ syndrome. The physical separation of our islands from mainland Europe limits our recycling capacity and resale opportunities, meaning that recycling companies incur higher costs to transport materials—an island problem.

The waste cycle is taxing—environmentally, socially, and economically. Economic costs are obvious and salient in the taxes spent by the government to run the whole operation on a daily basis. Environmental costs include air and sea pollution, including carbon emissions, together with negative effects on biodiversity and aesthetics. On a social level, citizens suffer the foul smells from treatment facilities and the nuisance caused by collection trucks. All of these issues means that treatment methods cannot be looked at in isolation. What is needed is a holistic, cradle-to-cradle (regenerative) approach, starting from the product inception until it is disposed of and, in some cases, recycled.

In a bid to amplify the conversation, we have conducted research that defines the existing flows in local waste management. Using material flow analysis (MFA), we have been able to generate a detailed picture of the waste produced by Maltese households, also known as the municipal waste system, and where that waste goes. In this way, we can determine where we stand and where we are heading with the new facilities introduced as part of the Waste Management Plan for 2014 to 2020.

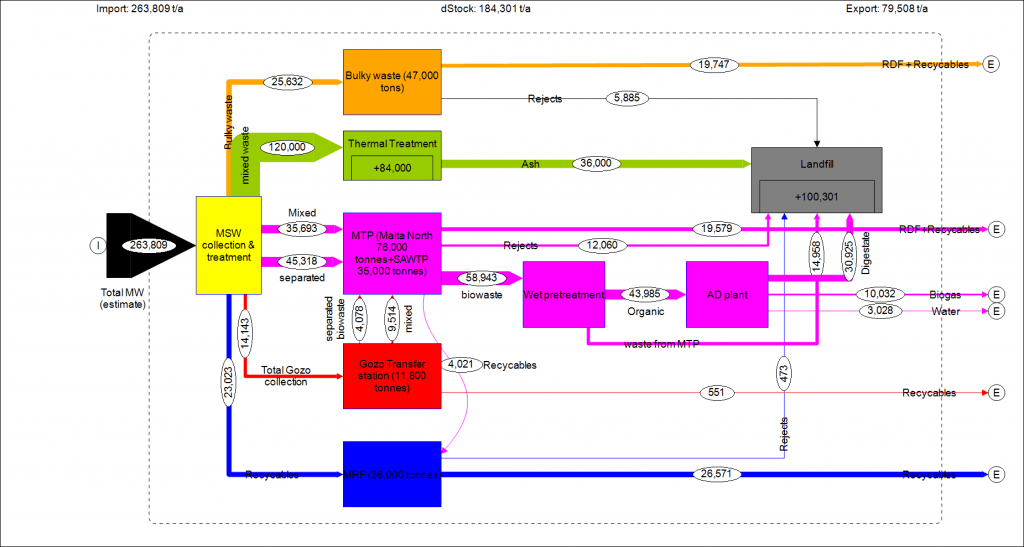

Following these plans, we have seen the introduction of a Mechanical Biological Treatment Plant, known as Malta North, which started its operations in 2016. The plant, which has a capacity of 76,000 tonnes per year, includes an anaerobic digester and a bulky waste plant able to handle a further 47,000 tonnes per year, while its waste transfer station can handle 11,800 tonnes per year, and a 120,000 tonne waste-to-energy plant may be on its way.

Crunching numbers

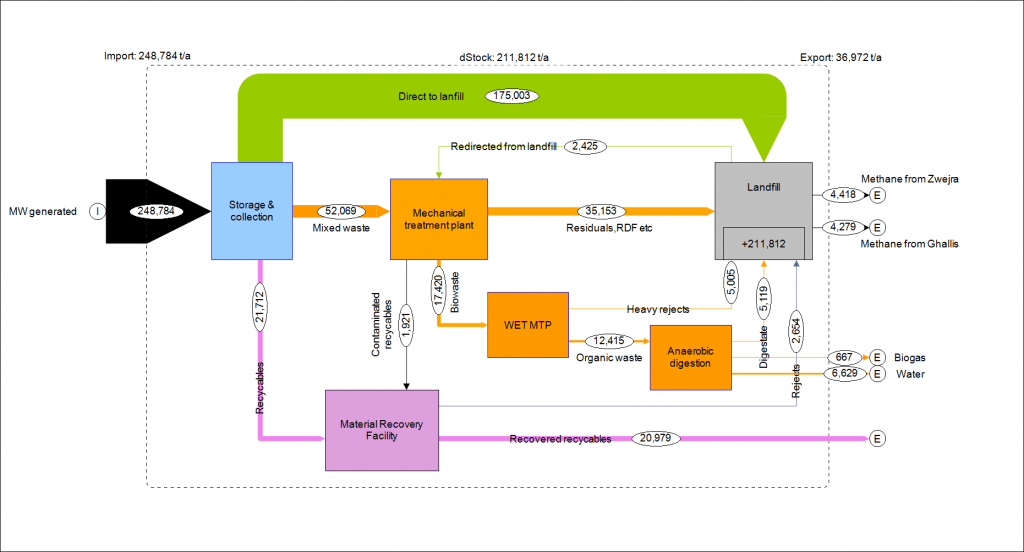

In Malta, municipal waste accounts for just 14% of total waste generated. Although it is not the most prevalent type of waste, this waste is the most visible and troublesome for society. So, what happens when the country has 248,784 tonnes of municipal waste to deal with?

The MFA provides a detailed picture of what goes on from collection point to disposal and recycling. Of those 248,784 tonnes, 175,003 tonnes (70.34%) are landfilled.

Of the remaining 73,781 tonnes (29.66%), 21,712 tonnes go into recycling facilities, and the remaining 52,069 tonnes are sent to the Mechanical Biological Treatment Plant (MBT), which is able to process either mixed municipal waste or, ideally, source-separated biowaste in a series of mechanical and biological treatment steps. The input received by the MBT is either landfilled (35,155 tonnes); further treated in the anaerobic digester (17,420 tonnes); or sent to the Material Recovery Facility (MRF) which treats recyclable waste like plastic and carton. This means that in reality, 81.14% of waste is landfilled, rather than the 70.03% (175,003 tonnes) previously claimed. A clear loss of material is occurring, particularly since no organic waste separation system is in place.

A system revised

The new waste treatment facilities drastically change the scenario. In 2018 it is expected that municipal waste will reach 263,809 tonnes, out of which 45.49% will be fed into the incinerator, eliminating the organic component and leaving the remaining ash as stable waste. With the other treatment facilities, the system will become more circular; more waste will reach the recycling market. For example, the bulky waste facility is estimated to handle 9.7% of all treatment, will be divided between Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) and recyclables, reducing the amount going back to the landfill to just 5,885 tonnes.

Despite all that, 38% of annual municipal waste will still need to be landfilled. Correct steps are being taken, but Malta’s waste problems are far from solved.

The 2018 MFA should serve as an eye-opener to policy makers. The introduction of a 120,000 tonne incinerator facility will not free the country from the need to landfill. We need to improve the at-source separation of biowaste and dry recyclables. If the current trends continue, facilities like the Material Recovery Facility and the bulky waste treatment will be underutilised, leaving more material ending up in the landfill than needed. We need to make sure we recover more material, thus enhancing the lifetime of the landfill and reducing the demand for yet another waste treatment facility that will surely be welcomed by no one.

In the long-term, households and companies need to reduce their waste. Whilst waste-to-energy has become standard in many countries, Malta needs to tackle its waste streams and their sources separately. Policies need to be set for hotels and restaurants, hospitals, the manufacturing sectors, and others depending on the waste they generate. Setting up focus groups to assess these situations would shed light on existing and quickly implementable possibilities to promote waste reduction and increase recycling. The country needs a holistic effort.

Such activities need to go hand in hand with research. More studies are needed on construction and demolition waste. More is needed to stop needing to dump waste at sea which is ruining our lifeline.

Proper environmental and social accounting are an absolute necessity, because, whilst Malta’s GDP shows vast economic growth, this is not synonymous with enhanced quality of life. Focusing wholly on GDP disregards that the economy profits from the natural, social, and human capital. A sad state of affairs indeed.

Note: The project is a collaboration between the University of Malta and Universita’ Autonoma de Barcelona.

Comments are closed for this article!