Psychedelics conjure images of hippies and tie-dye, or they may trigger images of junkies and erratic behaviours. However, psychedelic drugs are gaining a reputation as possible therapies for many psychiatric disorders, and researchers are not shy about praising their benefits. Meanwhile, psychedelics are illegal in most countries, deemed dangerous, and their use socially condemned. THINK explores the ambiguity behind this class of drugs.

For the past 20 years, a new trend in research has resurfaced the enormous therapeutic potential of psychedelics. Depression, substance abuse, anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) are just some of the conditions being targeted.

The therapeutic potential of psychedelics has long been known in the scientific field. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was used extensively in the 50s and early 60s as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. However, with the United Nations’ 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, LSD became hard to access, and research was halted. Like LSD, other psychedelics such as psilocybin, extracted from various fungi, and MDMA (the main component in Ecstasy) were studied and later disregarded as dangerous drugs of abuse.

Hyped by science but banned by governments, how can these substances bring such polarizing views?

What are Psychedelics?

Psychedelics are a subtype of drugs known to bind to specific receptors in the brain. The way in which psychedelics cause their hallucinogenic and therapeutic effects is yet unknown.

What we can tell is that by binding to 5-HT2A receptors (which regulate serotonin) psychedelics alter serotonin signalling in the brain. By doing so, they can influence many biological functions, such as learning and memory, mood, motor behaviour, and even pain.

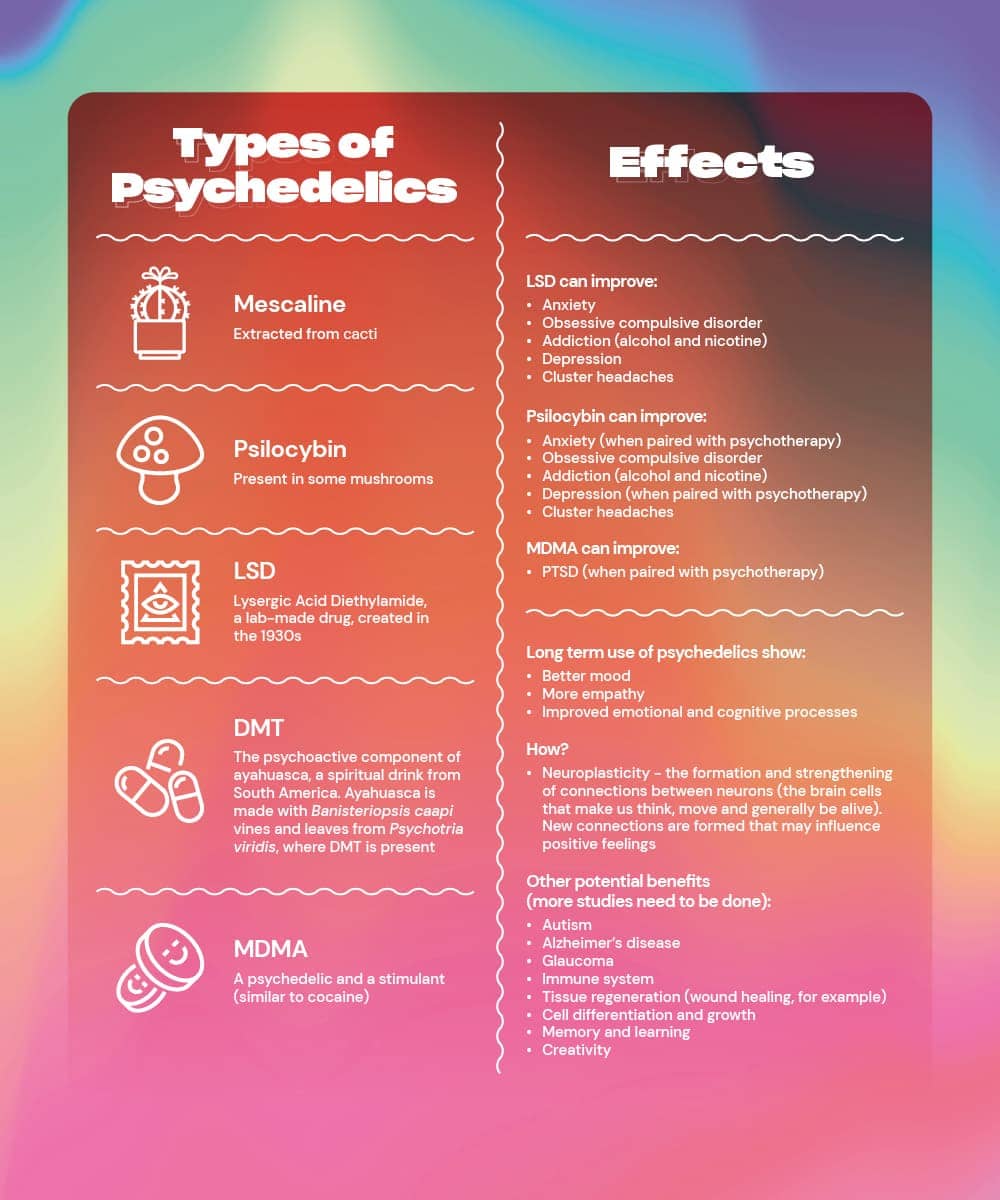

Classic psychedelics include mescaline (a natural hallucinogenic extracted from some species of cacti), psilocybin, LSD, and DMT (present in ayahuasca, a spiritual and religious drink from indigenous communities in South America). MDMA can be considered a psychedelic, although due to its effects, it can also be classified as a stimulant (similar to cocaine).

Users of psychedelics often report increased empathy and a change of awareness towards the world or one’s self. These types of drugs are highly sought after as a tool for spiritual journeys as they open ‘the doors of perception,’ as Huxley puts it.

For example, during episode 242 of the podcast Making Sense by Sam Harris, Dr James Fadiman (a psychologist and researcher in psychedelics) describes one psilocybin induced trip:

“Some of my cherished beliefs were disassembled about what was valuable and not valuable in my life. It wasn’t a therapeutic breakthrough but just an awareness that there was more to the way the world was. But it was still me, it was still my personality and my issues.”

Fadiman advocates that taking small doses of LSD, psilocybin, and similar psychoactives, following a particular schedule, can help improve mood and ease some disorders without the visual hallucinations of normal doses. Although his evidence is anecdotal, it may be that individuals can benefit from psychedelics without entering an altered psychological state. So in what instances may psychedelics be beneficial?

Therapeutic effects

To summarize a long and complex list of studies and observations, both LSD and psilocybin have shown positive effects in the treatment of anxiety, OCD, cluster headaches, alcohol and nicotine addiction, and depression.

Looking at initial studies from the 60s, a dose of LSD could help treat addiction. More recent clinical studies found that psilocybin, in combination with psychotherapy, can help alleviate anxiety and depression in terminal cancer patients, in addition to helping treat alcohol and nicotine addiction. What are the workings behind these promising results? That requires more research, but a possible explanation is that “psilocybin might help break the addictive pattern of thoughts and behaviors […] thus helping people to quit the habit.”

In a recent study, Psilocybin combined with therapy improved depressive symptoms. As one participant explained to BBC News, “The drug gives us part of a healing process.” In this study, brain scans showed that the psychedelic increased the connectivity between areas of the brain, which in some cases led participants to feel more connected with their reality. However, taking the drug also caused some “dark feelings”.

Another possible application for psychedelics is treatment for cluster headaches, the most severe type of headaches, which cause extreme pain. At the moment, the only treatments available to help decrease pain are oxygen masks or sumatriptan injections. Studies suggest that LSD and psilocybin can stop on-going attacks and increase the time between episodes.

And although MDMA’s classification as a psychedelic is debatable, it has revealed its potential as a therapy for PTSD, again when coupled with psychotherapy.

Due to their effects on the 5-HT2A receptor and serotonin signalling, psychedelics may be potential therapeutics for other conditions, but there are insufficient studies to come to conclusions just yet. The bucket list of future studies includes conditions such as autism, Alzheimer’s disease, and glaucoma, as well as assessing effects on the immune system, cell differentiation and growth, tissue regeneration, interaction with memory and learning, and improvement of creativity.

Interestingly, many sources highlight the long-term effects of psychedelic consumption, like better mood, increased empathy, or a more optimistic take on life. Besides the long term effects of microdosing and the initial 60’s studies on addiction, modern clinical research reports that psilocybin and ayahuasca, improve emotional and cognitive processes for up to 4 weeks.

The persistent effects after the substance has cleared from the blood suggests a biological adaptation, namely neuroplasticity, which has been associated with learning and memory. Studies suggest that the beneficial effects of psychedelics are related to the formation and strengthening of the neuronal connections in the brain, but more studies are required to understand if these structural changes are responsible for the long-term effects of the drugs.

Risks

There are a panoply of reasons for taking psychedelics. Some do it to cope with psychiatric disorders, others for the spiritual experience, the opportunity to connect with the foggy thoughts that our daily lives keep us from acknowledging. And maybe some do it to see pretty colours. No matter the reason, as with any drug, psychedelics bring considerable risks that need to be accounted for.

First, we need to consider that the drugs one buys from a dealer are not the same pure and controlled substances researchers study in labs. As Dr Godwin Sammut, scientific officer with the Faculty of Science, Department of Chemistry at the University of Malta and court report expert in forensic toxicology, explains, the drugs one gets from a dealer are rarely pure, and the list of substances seeping into the streets increase everyday.

Sammut refers to LSD, usually distributed as blotting papers, as an example. When analyzing the blotting papers being distributed in Malta, LSD is not the only substance detected. Buying a bag of magic mushrooms poses a similar challenge — you can never be sure which species you have been dealt, and mushrooms can go from innocuous to deathly poisonous. Something else not accounted for is potency. One can never be sure of what is inside a small pill, much less how much of it is present.

According to Sammut, the hallucinogenic effect, with altered vision and surrounding awareness, can pose a danger in itself. Erratic behaviours, falls, or other accidents can cause harm to the user or others surrounding them.

Nonetheless, between 1993 and 2014 in the UK, only 6 reported deaths were related to the use of LSD or Psilocybin. Unlike other drugs, psychedelics are not addictive, and the risk of harmful overdose is very low. A paper from 2020 looked for cases of LSD overdose and found 3 case reports (2 in 2000 and 1 in 2015). Here, overdose refers to the ingestion of doses much larger than the ones taken in recreational contexts. The three individuals who overdosed on LSD benefited from long-term effects after the overdose, such as decreased pain and alleviation of morphine withdrawal symptoms.

Psychedelics should not be considered innocuous, however. Overdose symptoms can include nausea, anxiety, fever, and even seizures. Buying from the black market is like buying a mystery box, and you never know what you are getting in the mix.

Then there is the risk of a “bad trip” — featuring scary hallucinations, anxiety, and even psychosis symptoms, which can lead users to act erratically. This is one of the reasons why many advocates for psychedelic use recommend the use of a guide.

If you read this article looking for the answer to “Are psychedelics good or bad?”, the answer is: both. They are drugs, after all, and their effect on our brain chemistry and structure is not fully understood. Concurrently, the therapeutic potential is immense and the prospects of helping understand the human brain exciting. Far out, man.

Further Reading

de Vos, C., Mason, N., & Kuypers, K. (2021). Psychedelics and Neuroplasticity: A Systematic Review Unraveling the Biological Underpinnings of Psychedelics. Frontiers In Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724606

Haden, M., & Woods, B. (2020). LSD Overdoses: Three Case Reports. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs, 81(1), 115-118. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2020.81.115

Lattin, D. (2017). How the War on Drugs Halted Research Into the Potential Benefits of Psychedelics. Slate Magazine. Retrieved 23 November 2021, from https://slate.com/technology/2017/01/the-war-on-drugs-halted-research-into-the-potential-benefits-of-psychedelics.html.

Muthukumaraswamy, S., Carhart-Harris, R., Moran, R., Brookes, M., Williams, T., & Errtizoe, D. et al. (2013). Broadband Cortical Desynchronization Underlies the Human Psychedelic State. Journal Of Neuroscience, 33(38), 15171-15183. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.2063-13.2013

Nichols, D. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 68(2), 264-355. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

Number of deaths from selected psychedelic substances: 1993 to 2014 – Office for National Statistics. Ons.gov.uk. (2016). Retrieved 23 November 2021, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/adhocs/005757numberofdeathsfromselectedpsychedelicsubstances1993to2014.

Osório, F., Sanches, R., Macedo, L., dos Santos, R., Maia-de-Oliveira, J., & Wichert-Ana, L. et al. (2015). Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: a preliminary report. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria, 37(1), 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1496

Psilocybin for Tobacco Addiction Study Receives First Federal Psychedelics Grant for 50 Years. Neuroscience from Technology Networks. (2021). Retrieved 23 November 2021, from https://www.technologynetworks.com/neuroscience/news/psilocybin-for-tobacco-addiction-study-receives-first-federal-psychedelics-grant-for-50-years-354912?fbclid=IwAR2XQnhNJM3Q0To3gG4nKPkocz6avbS3EyfaAtWGIcfbTc25lf56VEy7t9Y.

Tatala, D. (2020). Every psychedelic study currently going on in Europe. ICPR 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2021, from https://icpr2020.net/europes-psychedelic-science-renaissance/.

Author

-

Antónia was a Biologist, once upon a time. She transitioned from the glamorous world of lab benches and international conferences to her one true love - Science Communication. Antónia works as a freelance science writer and also manages social media for THINK. In her free time, she pets street cats and educates people on Portuguese gastronomy - often against their will.

View all posts

Comments are closed for this article!