Calorie-counting and crash diets may seem like the most accessible ways to get in shape, but a focus on what’s actually in the food we eat might reveal that staying healthy doesn’t need to be as difficult as we think… THINK speaks to University of Malta experts to find out the real deal.

As the sparkle of our ‘new year, new me’ resolutions begins to fade, it might be tempting to fall back into old habits. When it comes to food, we might think it’s enough to just eat less and exercise, but there’s more to it than that. THINK had a sit-down with University of Malta Associate Professor Suzanne Piscopo (Faculty of Education) to discuss just how people can get the best out of the foods they eat by focusing on nutrient density.

Making sense of Nutrient Density

Piscopo first came across the term and concept of nutrient density when she attended a nutrition conference in the US whilst reading for her master’s degree in Canada in the early 90s.

Nutrient density is essentially the practice of looking at the number and variety of nutrients in a particular food: the nutrient quality.

‘At the time, there was a focus on creating new food-based dietary guidelines, so researchers were placing foods into different food groups,’ she said, adding that each food item within the group was then rated with a star system rating.

‘For instance, salami and beef both fall into the same group, but the star rating they are given largely depends on the benefits they present. Put simply, beef contains protein, vitamins, iron, and some fats, whereas salami contains more fats as well as elevated levels of sodium. This means that beef will have a better star rating than salami, essentially.’

Nowadays, nutritionists have moved on from talking about star ratings, but it’s easy to see how the system has formed the backbone of modern nutrition profiles.

‘Now, we are essentially talking about creating profiles and ratings based on desirable vs undesirable nutrients in the foods we eat, and that’s what we mean when we talk about nutrient density. It is essentially the practice of looking at the number and variety of nutrients in a particular food: the nutrient quality.’

Piscopo explained that ‘nutrient-dense foods’ are determined by the presence of favourable nutrients like vitamins, minerals, proteins, so-called healthy fats, and fibre, as opposed to less favourable ones like saturated fats, sugars, and salt. At the same time, the lower the calorie count the better.

‘The comparisons and calculations take place in terms of nutrients per calorie or nutrients per weight. For instance, you could have two pieces of bread weighing the same, but one is wholemeal, and the other is white bread. Basically, the wholemeal piece contains more nutrients than the white, so it will be the more nutrient-dense food item. Similarly, the calculation and comparison can be made on a calorie basis. So for instance, you can have two slices of pizza adding up to two hundred calories each, but one contains cheese and vegetable toppings, and the other has only cheese and ham. Naturally, the vegetable pizza has more beneficial nutrients than the other one, so it would be more nutrient dense.’

Piscopo explained that some foods or food groups are naturally more nutrient dense than others (namely vegetables, fruits, lean meats, seafood, low-fat dairy products, pulses, eggs, and nuts), but also added that nutrient density could be handy to decide which foods to choose from within the same group.

‘Fruits are all nutrient dense, for example, but apricots would be more so than watermelon, purely because of their higher vitamins, minerals, and fibre content.’

Why should people care?

Perhaps one of the first things the more sceptical of us will wonder is: why does all this matter? And how is this different from dieting fads such as calorie counting? Piscopo maintains that there are actually three aspects where nutrient density can impact us: health-wise, economically, and ecologically.

‘People are recommended a certain amount of food or calories every day based on their age, gender, and level of physical activity, so really we should try to get the best nutrition out of that allowance. Ultimately, this will simply allow us to get better bang for our buck,’ Piscopo clarifies.

She explains that nutrient density is superior to calorie density because calorie-dense foods can eat up our calorie budgets quite quickly, whereas focusing on nutrient density might allow us to eat more satisfying quantities of healthier food in the long run. Calorie-dense foods tend to be packed with fats and sugars, so ultimately, they end up being nutrient-poor, which means that calorie counting alone might not be the best option for health. Interestingly, the US’s latest dietary guidelines (published in 2020) have shifted focus onto promoting more nutrient-dense foods (whilst staying within calorie limits) as opposed to highlighting calorie dense ones.

‘I often get asked for advice and meal plans by people who are trying to lose weight for whatever health or aesthetic reason. My interest in the subject was first piqued precisely because I needed to understand how to best advise people to get the best nutrition from the limited bank of calories they were allowed to achieve their goals.’

Piscopo also goes on to explain that her interest intensified and has taken a slightly different slant recently, as she has grown more interested in the financial aspect of nutrition.

‘I’ve become increasingly interested in facilitating the nutritional needs of low-income families and individuals. It’s far too easy and cheap to access the not-so-healthy foods, but making people more aware of nutrient density will ultimately ensure better nutrition for less money. It will ensure that people spend their limited money on foods that will be good for them, rather than foods rich in sugars, salt, and fats,’ she clarifies.

Piscopo explains how nutrient density can affect the environment. Researchers are now analysing the greenhouse gas emissions of foods along the supply chain.

‘You can look at similar products, like a jar of tomatoes, for instance, and compare that to tinned tomatoes to decide which one is best both in terms of its nutritional value and in terms of the carbon footprint of its production, transport, storage, and use.’

She adds that there are also studies looking into the water consumption of specific food products, as well as land use to make certain comparisons.

‘These studies will look into how much water you need to raise livestock or to water plants, as well as how much nutrition you can gain from a designated area of land. For example, if you use one hundred square metres of land to raise a few cattle, you can get a certain amount of protein, vitamins, and minerals from their meat, whereas if you use that land to grow beans, the yield of food and nutrients will be higher.’

For Piscopo, these calculations can allow the agriculture industry to make better choices in terms of nutritional value and how best to use the land available to feed people with less harm to the planet.

Making nutrients more visible

As Piscopo’s research has already shown, a focus on nutrient-dense foods can be beneficial in various aspects. Indeed many countries already use nutrition density as one of the main recommendations to manage weight loss and access lower cost foods. In fact, Piscopo hopes that nutrient profiling will become more mainstream and even become present locally on product labelling and packaging.

‘France for instance, has introduced a nutriscore label on food products in the past three years, and this has allowed consumers to make more informed choices. The score basically gives foods a rating between A and E (with A being the healthiest) depending on the nutritional value. There are currently talks about whether this should be an EU-wide scheme, as it has had fairly positive results.’

Piscopo points out that the scheme would not just allow consumers to make more informed decisions, but it would also prompt food production companies to improve their recipes and aim for better nutrient profiles for labelling purposes.

‘I think having some sort of labelling would put consumers in a much better position, as I believe a lot of issues come from the public simply not knowing how to maximise nutrients and minimise calories,’ she says.

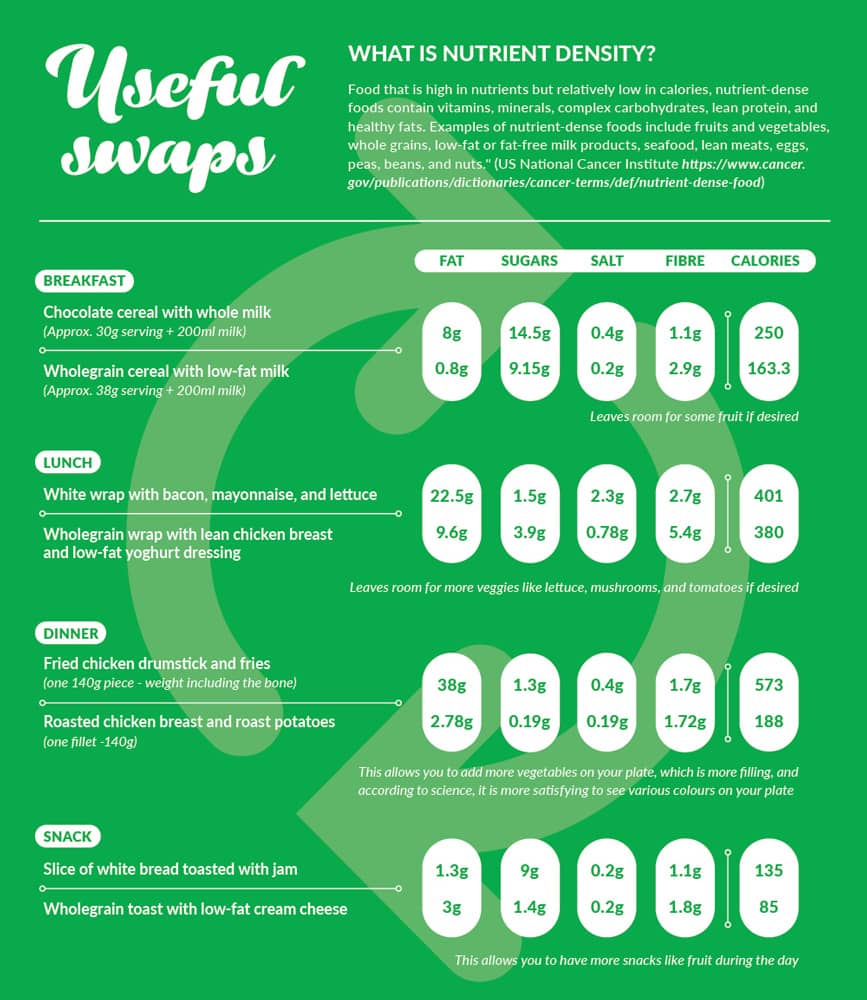

Piscopo highlights her point by pointing out a few simple and healthy swaps that could lead towards a more nutritious lifestyle. She goes on to add that as part of her teaching, she shares a tasty and healthy muffin recipe featuring the humble red kidney bean as its main ingredient with her students. As I clearly can’t hide my intrigue and slight skepticism, she assures me they’re surprisingly good, and I can’t wait to test them myself…

I am left to wonder how such labelling might impact my determination for new year resolutions, which often slowly fizzles away come spring. As the call of nutrient-poor take-outs beckons me ever more enticingly, Piscopo reassures me that following a nutritious, plant-forward diet is often easier than it seems. She suggests a series of simple swaps from less nutrient-dense food items to more dense ones. The gist is that focusing on plant-based foods and wholegrain products can have a deep impact, simple advice that can change our health and lives.

Nutrient-dense Foods

- Whole grains – oats and oatmeal, quinoa (technically a pseudo grain), barley, bulgur, wholegrain/brown rice, and whole-wheat pastas and breads

- Legumes – all kinds of beans, lentils, chickpeas, split peas, black-eyed peas

- Vegetables – leafy green vegetables (ex spinach, chard, beet greens, kale, endive, rucola, leaf or romaine lettuce), red pepper, kohlrabi, scallions, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, carrot, pumpkin, sweet potatoes, parsley, chives

- Meats and Dairy – lean chicken, rabbit, (sustainably sourced) oily or local fish, eggs, ricotta, low fat milk and yoghurt

- Fruit – all kinds of berries, kiwis, avocado, cantaloupe melon, apricots, peaches, nectarines, tangerines, oranges, pomegranate, starfruit, papaya, mango, apples, banana

- Nuts – peanuts (technically a legume), almonds, pistachios, cashews, walnuts, hazelnuts

- Plant oils -particularly virgin olive oil

Author

-

Martina writes on a freelance basis for a number of publications including Think Magazine. She works in children’s publishing in London and has a background in journalism. Previous writing credits include MaltaToday and other other local content writing agencies. Her favourite topics to write about include lifestyle, culture and health issues. She also enjoys interviewing people and learning about new topics as part of her research. She holds an MA in Publishing and previously read for a BA in English at the UM. In her free-time, she can be found sipping tea in coffee shops, reading or trying out new hobbies.

View all posts

Comments are closed for this article!