URNA is Malta’s response to the 5th edition of the London Design Biennale 2025. THINK speaks to curator Andrew Borg Wirth and Arts Council Malta Internationalisation Executive Romina Delia to learn how this project seeks to create a connection between souls when experiencing a loss.

With curator Andrew Borg Wirth at the helm of URNA’s development, he aims to imbue the very personal experience of death with a fresh take on commonality and communality. In this way, the project intends to suggest a link or a bond between souls in what is otherwise often perceived as a singular experience. As such, in the midst of ‘lots of international attention from the press’, as Internationalisation Executive Romina Delia puts it, Borg Wirth and his team hope to ‘really push through their limits’ by delving into the subject of cremation.

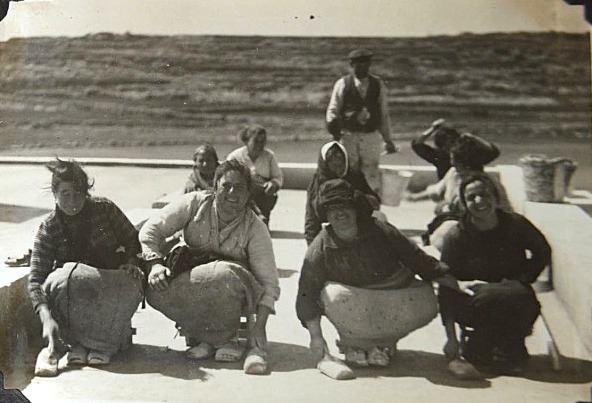

(Photo courtesy of the URNA Team)

With curator Andrew Borg Wirth at the helm of URNA’s development, he aims to imbue the very personal experience of death with a fresh take on commonality and communality. In this way, the project intends to suggest a link or a bond between souls in what is otherwise often perceived as a singular experience. As such, in the midst of ‘lots of international attention from the press’, as Internationalisation Executive Romina Delia puts it, Borg Wirth and his team hope to ‘really push through their limits’ by delving into the subject of cremation.

URNA: An Idea of Death

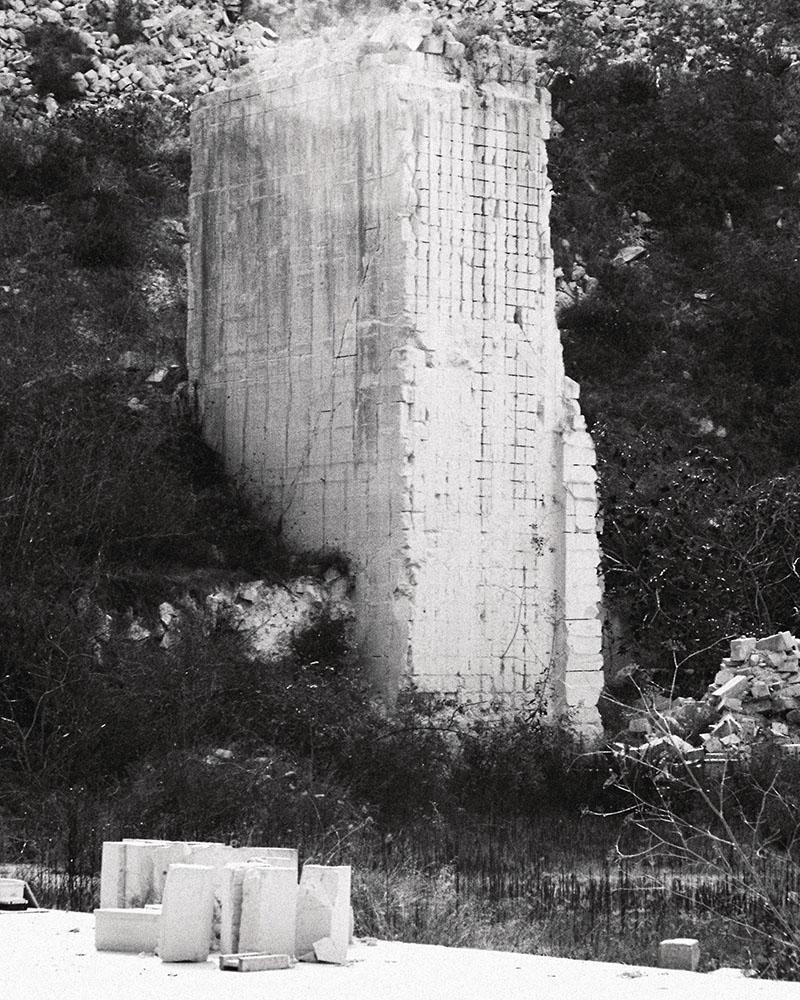

After having achieved great success at Somerset House with Urban Fabric during their first-ever appearance at the London Design Biennale in 2023, the Malta Pavilion team now aims to outdo themselves a second time. Now, the Pavilion moves away from the idea of earthen fabric and Phoenician influences to explore the subject of cremation and its associated implications with the end of life. Alongside a team of fellow architects and designers together with the help of supporters at Halmann Vella, URNA takes the form of a large spherical installation composed of many layers of reconstituted stones. Yet the project’s significance extends beyond its physical presentation. More so than just a large urn, Borg Wirth states that they are ‘designing a ritual which will stand the test of time’. In addition, the design outcome may be defined as something universal in that it is ‘not necessarily inhibited by our traditions, our habits, or our personal traits’. There is a conscious effort made to trade in the common associations of death with the personal and the individual in favour of a sense of the universal.

Often, the cemetery or crematorium is a site not just of death but of extreme personalisation. Urns and tombstones alike are marked and decorated according to personal and carefully described specifications to uphold a sense of meaning. And yet, such meaning often cannot be transmitted, felt, or understood by those who should come to view these monuments of people now no more. URNA’s plain stone opposes the plentiful markings and materials often found in such mementoes because this idea of the personal is not the message the team of URNA is trying to deliver. On the contrary, the universal is – that idea of the common, the communal, in an attempt to create from Malta’s natural resources something that can be applied to contexts everywhere. In this way, anyone viewing URNA may identify a sense of meaning. ‘Rather than you fitting into an urn, you become one part of a much larger urn,’ as Borg Wirth puts it.

(Photos courtesy of Thomas Mifsud)

URNA: Universal

You are not alone in death. The end of life is a shared experience and, in a sense, something which connects all human beings beyond even the barriers of language and culture. The end of life, when viewed this way, is unmistakenly Hamletic, though not in particular reference to the nature of the play’s titular character, but rather to the ending of the iconic play itself. With the ending best summarised in the condensed words of Barbra Lindgren’s Look Hamlet – ‘Now everyone dead’, death need not always be viewed as a sole experience. It may not even be viewed as the end, either.

This is, of course, the intrinsic aim of design. Borg Wirth explains that ‘design alters the way we exist and the way we arrange ourselves’. It reconfigures established notions of various aspects of living based on the technology and the resources of our time. The installation at Somerset House will invite viewers to expose themselves to this idea of a communal death. In this regard, Borg Wirth hopes that this idea that one is a part of something communal in death will stick and solidify itself into future thought. Of course, the desired message’s radicality and effectiveness are still up for debate, yet what is certain is that the notion that one is not alone in death does give quite a notable shade of hope.

(Images courtesy of Tanil Raif)

URNA: Communal

Combining his prior interest in cremation and crematoria with this recognised desire to be interdisciplinary in his practice, the URNA project may arguably be an extension not simply of the curator himself but rather what defines him. The importance given to the notion of the interdisciplinary reflects itself in the team forming the project as a whole, with architects, directors, photographers, and filmmakers merging their expertise to craft this innovative piece. In fact, accompanying the installation, all of the artistic minds on the team will also leave their mark through a book they are collectively writing and curating. The touch of Andrew Borg Wirth, Anthony Bonnici, Tanil Raif, Thomas Mifsud, Matthew Attard Navarro, Anne Immelé, and Stephanie Sant is found in the installation as well as in this book. Borg Wirth hopes that as people will hopefully visualise others in the blankness of the boulders, so too will they be recognised as well. Therefore, the project has its function as well of synthesising ‘all of our aspirations and feelings and thinkings’, Borg Wirth states. URNA is hence, them, as it is everyone.

(Images courtesy of Ebejer Bonnici)

URNA: After

Before, during and after the project’s run, the team hopes to create a space where the ideas suggested by the project may grow. As such, interdisciplinary workshops will be carried out with the scope of widening the goalpost as to what it means to define the architectural profession as a role. With this, URNA’s curator hopes to inject that same interdisciplinary attitude he has found essential in his daily life into the implications of an architect’s prospects – to really explain what architects can go out to be and do. But of course, this is just like anything he has done before – bringing people together to create something meaningful. In this case, different academic institutions will come together to create these workshops and aid in research.

Arts Council Malta Executive Romina Delia says it best: ‘Once you have a good concept and a good strong team, you’re aiming for the stars’, thereby describing a tried-and-tested formula for success in these types of competitions. This is the spirit of the London Design Biennale at the end of the day – ‘It’s having these amazing designers and architects all come up with innovative ideas of what we can do in the future to make things better.’ And at the end of one’s life? Ideally, we go through that together as well. This is URNA at its core.

The Malta Pavilion at the London Design Biennale is commissioned by Arts Council Malta. The URNA Team would like to thank Halmann Vella, Gasan Foundation, Embassy of France in Malta, Malta Enterprise, Deloitte Foundation, Visit Malta, KM Malta Airlines, and all supporters for making this project possible.

Comments are closed for this article!