Commissioned over half a millennium ago, Antonello Gagini’s Madonna and Child has been silently standing tall in a Franciscan church in Rabat for the past five centuries. Little was known about the Renaissance sculpture, but a recent study is tracing the statue’s history. Caroline Curmi speaks to art historian Dr Charlene Vella and University of Malta student Jamie Farrugia about their findings.

When one directs their thoughts to local religious iconography, the Maltese Islands’ opulent and resplendent Baroque churches undoubtedly come to mind first. Indeed, the many prime examples scattered across the islands coupled with Malta’s fascination with the Baroque have unwittingly caused several other major art periods to be cast aside in public memory. ‘The Renaissance in Malta is often overlooked,’ University of Malta Art History lecturer Dr Charlene Vella confirms, insisting that such works ‘deserve scholarly attention’ too.

The Knights of St John were the largest commissioners of baroque art in Malta, filling it with many masterpieces, but Vella draws attention to other surviving artworks which predate their time. Examples include two Antonio de Saliba paintings and Antonello Gagini’s Madonna and Child – all housed at the Church of Santa Maria di Gesù in Rabat, Malta. The church is a great source of fascination and inspiration for Vella and has featured in her own master’s and doctoral studies: ‘It has a wonderful history, an intriguing cloister of artefacts,’ she says. Indeed, over the past decade Vella has supported and secured funding for the study and conservation of Renaissance paintings across Malta. Her latest study has seen a natural progression into sculpture.

Gagini’s Madonna and Child was commissioned on 23rd February 1504. The statue was delivered a few months later around June, in time for the Corpus Christi feast. There is no documentation that sheds light on the way the mammoth statue – whose weight exceeds 380kgs – was transported from Valletta’s Grand Harbour to Rabat: ‘It must have been the Maltese Franciscan Observants who handled this, but there are no records of it,’ Vella muses.

The study was funded by the Majjistral Action Group Foundation under the LEADER Programme 2014-2020. It was after the diagnostic testing, conservation, restoration, and 3D scanning of the statue. Its findings were analysed and supplemented further by University of Malta art history student Jamie Farrugia’s BA dissertation research, which merged scientific study with art history to obtain a deeper understanding of the commission. ‘The sculpture was analysed from a visual and stylistic perspective and compared to Sicilian counterparts to assess its success as a Renaissance work within Gagini’s oeuvre,’ Farrugia explains.

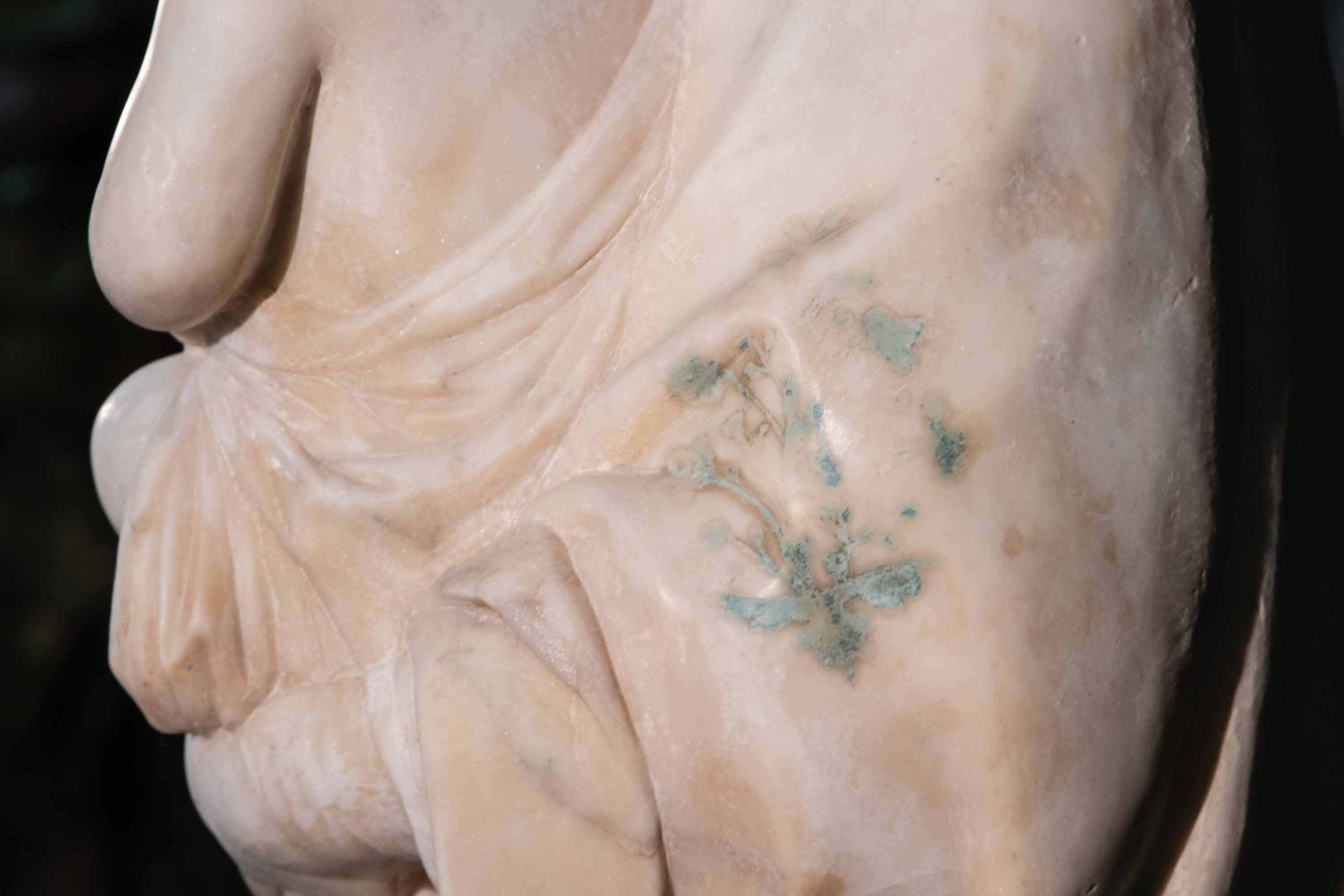

The presence of so much gilding was probably paired with a beautiful bright azurite blue which has since been completely lost

Jamie Farrugia

Farrugia’s research saw her analyse pigment profiles extracted from the statue since much of this has been lost through the centuries. Through this, she was able to ‘[…] connect them to [her] art history research, while proposing hypothetical 2D-reconstructions of the Madonna and Child as it may have looked in 1504.’

Preserved in Paint

Dr Davide Melica (Consulenza e Diagnostica per il Restauro e la Conservazione) carried out the scientific testing to extract pigments from the statue followed by an identification test. A total of six samples of approximately 1mm2 were removed from the Virgin and Child’s hair and dress; the latter had a layer of repainted brownish pigment as well as a yellow wax. Various areas from the left-side of the Virgin’s mantle also display repainting interventions in red and yellow hues. They found that the statue had at least 2 instances of later intervention through repainting or wax applications.

‘In one stratigraphic layer — that is, layered materials over a period of time — at least two individual repaintings have been identified,’ Farrugia explains.

Some original paint residue was located in a green layer of verderame (or verdigris) present in certain areas on the Virgin and Child’s heads, and as floral patterns on the Virgin’s dress. ‘This is indicative of Antonello Gagini’s use of an old technique used by masters,’ Farrugia explains, who goes on to highlight the sculptor’s methodology: ‘The verderame (pigment) was mixed with linseed oil and painted onto the marble surface, and then the gilding was applied onto it, where the verderame would act as a mordant for the gold,’ she says. She elaborates that while on first viewing, the statue appears white to the naked eye, the presence of the verderame confirms that gilding was present wherever the green layer was found. This means that both the Virgin and the Child’s hair, as well as the sizable floral patterns adorning the mantle were completely gilded. While the Virgin and Child’s eyebrows may also have been gilded, there is a higher probability that they were painted in a natural ochre. Within the inner sides of the drapery folds, very light traces of possible azurite were identified. ‘The presence of so much gilding was probably paired with a beautiful bright azurite blue which has since been completely lost,’ Farrugia says, a speculation based on her readings of original documentation of Sicilian sculptures of the time.

Such a stunning hue is not the only thing lost from the statue. Its octagonal marble pedestal – carved in relief and portraying the Stigmatization of St Francis on the front, as well as two half-length images of St Paul and St Francis — was moved to the National Collection in 1911. Today, it is exhibited at Valletta’s MUŻA arts museum. ‘All the figures on the pedestal have been defaced, probably intentionally, at an unknown period in the past,’ Vella explains, adding that the pedestal carries the artist’s signature.

A hole in the Child’s hand can also be observed, which Vella confirms could have once held a flower or a bird. Detailing the meaning behind such iconography, Vella refers to the 1515 Renaissance altarpiece by Messinese artist Antonio de Saliba portraying the Madonna and Child with Angels. There, the Virgin is depicted holding a flower and a bird, specifically a goldfinch. ‘The red flower in question is a passiflora, often associated with Christ’s Passion, and the goldfinch — a small bird with a splash of red on its head — is known to make its nest from thorns, and therefore another link to Christ’s passion and crucifixion. The same could possibly have appeared on the Gagini sculpture,’ Vella explains. ‘This means that even when we see an image of the young mother and her infant son, there is a lot that prefigures Christ’s suffering and death for humanity’s salvation which is typical of Renaissance iconography.’

Over 500 years’ worth of history are preserved in the statue’s multiple layers. It is a unique and precious historical and artistic artefact which deserves preservation. Although it is not the oldest Renaissance specimen found on the island (the earlier example is believed to be a holy water stoup in Għarb by Antonello Gagini’s father, Domenico, dated to 1474), Gagini’s Madonna and Child predates the arrival of the Knights of St John. These facts make the statue vital to preserve. Today’s studies offer insight into the Renaissance era in Malta, and hopefully, they will act as a catalyst for more in-depth research to better appreciate Malta’s Renaissance past.

Now completed, the sculpture has been settled back into its place in the Ta’ Ġieżu church in Rabat, where it can be appreciated by the public. Speaking about her time on the project, Farrugia highlights the excitement that comes from uncovering the layers of history which had previously been left unstudied. ‘Confirming the true visual identity of the work based on factual pigment samples is truly ground-breaking.’

Two 3D sketches of Gagini’s Madonna and Child were also created for the project. They can be viewed for free through the following links:

pre-restoration https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/madonna-and-jesus-37038ff944ef4953bc049352c4a04b84

post-restoration https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/madonna-and-jesus-37038ff944ef4953bc049352c4a04b84

Comments are closed for this article!