Urban areas suffer from crippling traffic issues and gross water wastage. The University of Malta could become a living experiment to test innovative solutions to these problems. Words by Natasha Padfield.

Built environments need to evolve. Unharnessed, this evolution spirals out of control: buildings spring up haphazardly, traffic escalates, infrastructure crumbles. Malta has the highest proportion of built-up land in the EU according to Eurostat in 2013. Solutions are needed for us to continue enjoying our quality of life and natural resources. Only the strongest and most sustainable lines of action lead to a brighter future. But how do we choose which to take?

The Master Plan uses the University of Malta (UoM) as a pilot project to test cutting-edge remedies for urban problems. University suffers many issues symptomatic of a modern urban environment. Proposed residential and commercial complexes will increase the area’s mixed uses and population leading to a major restructuring. The plan intends to guide the evolution of the site over the next 20 years.

A team of ten Master’s students from the Faculty for the Built Environment have brought fresh ideas to the plan. Through a design workshop, they developed solutions to traffic and water management problems. Transport specialist Dr Odette Lewis and water governance researcher Dr Kevin Gatt supervised the workshop. I asked them what the future could hold.

Traffic management

Traffic management

Maltese drivers spend an average of 52 hours in traffic each year. Taming the traffic beast is no mean feat. Lewis explains that the workshop embraced a ‘holistic’ approach. The issue was investigated from various angles to identify the roles of different entities, from local councils to transport operators. The focus was on transport to University, parking, and circulation on campus. A mock Traffic Impact Statement was produced to test the team’s proposals. Similar reports are submitted to the Malta Environmental and Planning Authority as part of planning applications.

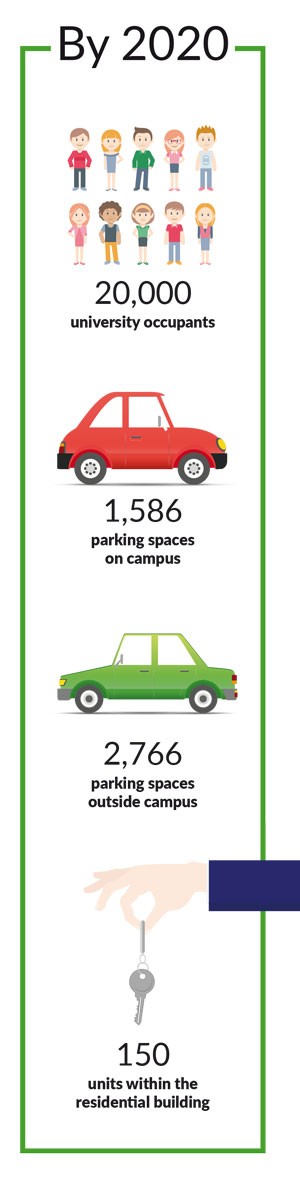

The team estimated that by 2020 the population will reach 20,000 with the proposed residential complex housing 158 residential units. Considering environmental considerations and authority restrictions, the number of parking spaces was

assumed to remain at current levels. Junction modelling software was used to simulate the impact of future commuters. Effort was centred on the roundabout junction between University and Mater Dei Hospital.

The Modal Split was key to the proposals. Results from the Green Travel Plan survey showed that 66% of students and staff used private cars, 22% public transport, and just 7% carpooled. University parking also overspills heavily onto surrounding residential areas, putting pressure on the whole of the Msida and Birkirkara area. Capping parking spaces on campus is a short-sighted solution if measures are not taken to alleviate parking pressure on the whole region.

A multi-pronged approach is needed to solve the crises. Students are wary of public transport because it is unreliable. Many lectures have been missed because of late buses. The architects used demographic projections to learn which localities will experience an increase in commuters. They studied bus frequencies to identify under-serviced routes.

Car sharing could be an easier solution to encourage. Parking restrictions and timed parking in residential areas would curb the overspill. However, limiting private car use without working on the other solutions would only frustrate commuters.

The plans give priority to pedestrians and public transport users. The entrance to campus would be a pedestrian plaza, with a public transport station. Traffic would flow from the roundabout to a route beneath the plaza and parking from the ring-road would be reallocated to underground areas. Parking management systems could also be introduced. Levelled parking would allocate spaces for students, staff, and visitors. From a technological aspect, apps can highlight free spaces and signs could inform drivers when an area is full. Detailed plans ensured that the proposed multi-level solutions could work within the area. Once tested at University, these systems could be implemented nationwide. Malta desperately needs to solve the traffic problem.

“The problems are there, they will remain there, and they will probably increase unless there is a change in mentality.”

Some plans might become real as many were well received by the University and the Green Travel Plan Committee. However, the biggest challenge is changing people’s behaviour. Lewis is adamant: ‘We agree there’s an issue with congestion and parking at University, but no one is willing to leave their car at home, no one is willing to share a car with someone else, and no one is willing to revert to public transport. So the problems are there, they will remain there, and they will probably increase unless there is a change in mentality.’ Only a joint effort will calm the traffic beast.

Water: reality check

Malta lands in the top 10 most water stressed places in the world. Water is Malta’s scarcest natural resource. Groundwater supplies around 45% of tap water but this source is threatened by illegal borehole use and fertiliser runoff. Three Reverse Osmosis plants turn salt water into fresh water to alleviate the burden on other sources soaking up millions of units of electricity a day. Malta has no fresh water bodies.

‘The fact that you open your tap and water flows gives a false sense of security. We still do not understand the value of water,’ Gatt comments. There is a contrast between Malta’s arid landscape and the volume of water storms bring. The resulting flooding gives an enormous surface run off that is not collected, adding more pressure on groundwater supplies because of poor water management.

Gatt oversees the water planning aspect of the University’s Master Plan. Like traffic, he wants to use it as a test-bed for new approaches to manage water for the whole country. Storm water management and waste water treatment are the plan’s two pillars.

“The fact that you open your tap and water flows, gives a false sense of security.”

The team began with a water audit of campus. They investigated water usage and efficiency of fittings like taps. Their assessment saw that campus was at risk of flooding and damage because of impermeable surfaces and inadequate reservoirs.

The solution is green. Gardens, green roofs, and living walls drain storm water naturally. Local plants are ideal since they are adapted to arid summers and intense, short rainfall in cooler months. These plants are usually shunned since they might not be considered as attractive but they require less watering in summer and cope better in winter than plants that are not well adapted to Malta’s climate.

Water collection would reduce disruptive flows into the flood prone Msida Valley. Cascaded reservoirs and basins could intercept overflows from existing reservoirs to target areas prone to flooding. Collected water can be used with minimal treatment for use in toilet flushing, irrigation, and fire-fighting. Gatt comments that ‘it is absurd that we flush toilets with drinking water’. In homes, one third of potable water consumption is used for toilet flushing.

Run off water could be diverted into a water treatment plant. A grey water treatment plant near campus would process all wastewater except that from toilets and kitchen sinks, because of the heavy solid material. A challenge in implementing a plant is the daily drastic swings in campus population and the drastic drop during holidays. One solution is a modular plant that can be partly shut down over weekends and summer recess. Another possibility is to divert water into the plant from the main sewage system. Treated water could then be used to replenish groundwater. Although low-risk technology to treat water to potable quality does exist, Gatt believes more education is needed before society will accept the value of such a plant.

The plant would provide water to the residential complex. The complex is that place where ecology meets comfort. Gatt’s research shows that in Maltese households water-saving technologies like low-flow taps and shower heads are not well received. Current building trends do not provide enough pressure to taps. New University buildings need to incorporate these technologies. Low-flow taps have a major impact: normal taps discharge around nine litres per minute while low-flow models reduce this to 4.5 litres per minute or less.

As well as showcasing water-conscious building design the Master Plan explains how to increase the sustainability of existing infrastructure. This injection of fresh ideas could save us from a water infrastructure crisis in future. But will society act on it?

Comments are closed for this article!