As an archipelago, the Maltese Islands have been a hotspot for seabird nesting since time immemorial. Marie Claire Gatt talks about her research and a major EU project determining how to protect far travelling seabirds. Photography by Jean Claude Vancell.

Sitting in pitch darkness on a hidden cliff ledge at l-Aħrax tal-Mellieħa (Malta), I listen intently to the ghostly calls of the seabirds, Yelkouan shearwaters (Garni, Puffinus yelkouan), as they return to their nests after a day foraging at sea. Like albatrosses in the southern hemisphere, shearwaters and petrels spend their life roaming the seas and oceans, feeding on fish, squid, and other marine animals, only approaching land during the breeding season to nest. Even then, these birds cover hundreds of kilometres at sea every day just to feed.

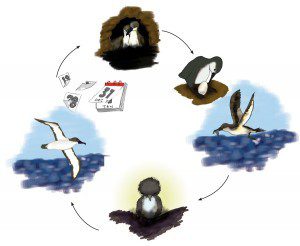

Back to the cliff ledge. I have just been slapped in the face by the wing of an unsuspecting Yelkouan as it returns to its nest hole. I pick up the confused bird and pass it to Ben Metzger, who reads out the identification number on the metal ring on its leg: EE01105. It is 2013 and Metzger is the Head of Research at the EU LIFE+ Malta Seabird Project, a conservation research project led by BirdLife Malta. This male bird was first handled in Malta in 2007 and fitted with this ring by seabird researcher John J. Borg; it has been breeding yearly at the same location ever since. Metzger and a team of colleagues and volunteers (such as me) have been building on past efforts by monitoring the three seabird species which nest on Malta’s coasts and islands: the Yelkouan shearwater, its close relative, the Scopoli’s shearwater (Ċiefa, Calonectris diomedea), and the tiny Mediterranean Storm petrel (Kanġu ta’ Filfla, Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis). Around 10% of the world’s population of the Yelkouan breed in Malta, while as much as 50% of Mediterranean Storm petrels breed in the rock scree of Filfla. I have been involved in this project since its start in 2011, and this experience inspired me to study the lives of this group of birds.

“Seabird behaviour is closely tied to the rhythms of marine life”

A year later and 2,850 km due west, I am standing outside the remote research station on Deserta Grande, Madeira, surrounded by Bulwer’s petrels (Bulweria bulwerii) swiftly manoeuvring around me to join their partners in nest burrows among the rock scree. I have flown out to the Madeiran archipelago from Manchester Metropolitan University to join the research group of two biologists from Lisbon studying the ecology and behaviour of the Bulwer’s petrel—a small, soot-coloured petrel which the Portuguese call Alma-negra—black soul!

Life at sea

Seabird behaviour is closely tied to the rhythms of marine life. The Bulwer’s petrel feeds on fish and squid species that occupy greater depths of the sea during the day compared to the night. These fish and squid follow plankton along their vertical migration up and down the water column. The plankton seem to sink to the darker waters to hide from predators, while returning to the surface at night to feed. They are at their most abundant at the surface during the new moon period when there is no moonlight. Their predators seem to follow them. Likewise, the Bulwer’s petrel. It can only feed from the sea surface so it hunts mostly at night. While on Deserta Grande, I investigated whether the Bulwer’s petrel’s hunting efficiency was being influenced by this predicted difference in food availability across the lunar cycle. To our surprise, it appeared as though these birds were managing to catch just as many fish and squid, no matter the moon cycle, during their breeding period. This raised more questions than it answered, as is typical of ecological studies, and more investigations were needed to figure them out. Other studies on bird activity outside the breeding season seem to suggest that Bulwer’s petrels can adjust their behaviour to get food when they need it most.

Seabirds are top predators in the marine environment. They hold an important place in the food web and reflect the health of the seas in their success. Unfortunately, they are also very vulnerable. Albatrosses, shearwaters and petrels pair with a single mate throughout their life and lay no more than a single egg every year. Both pair members take turns to incubate the egg for days at a time while the other parent is foraging. They nest in the same site all their life, returning every year to the same spot from halfway around the world. The chicks that make it then take between two to 12 years to reach sexual maturity in the different species. All these facts add up to a low birth rate and a high dependence on a stable habitat. The loss of just a few birds can have a big impact on the population.

While attached to their breeding colony, seabirds depend on food being relatively close to their nest to be able to regularly swap the incubation shift with their partner. When the chick hatches they need to bring back food at an even faster rate. While on Deserta Grande Island, I came across several Bulwer’s petrel’s eggs that had been abandoned by their parents; the birds may have either not found enough food in time to exchange incubation duties or died at sea. The major cause of incidental death is fishing gear. Fishermen do not intentionally target birds but the birds become entangled in their gear as they try to catch baited fish. A number of modifications to fishing gear are starting to be implemented in the southern hemisphere. These adjustments do not badly hamper fishing fleets. For example, in South Africa streamer lines on trawl cables were introduced that discourage the birds from approaching the fishing gear, reducing seabird bycatch by up to 99%. Other simple mitigation measures include weighting lines to quickly sink beyond the reach of foraging seabirds. Conservatively, 700, 000 seabirds are estimated to die globally as fisheries bycatch every year. The situation in the Mediterranean is not yet known.

Seabird numbers are also hit by overfishing; 80% of fish stocks are overexploited. Overfishing, pollution, and the degeneration of our seas result in increased stress for seabirds—and fishermen—to catch enough fish. Ship traffic, dumping, sea pollution, and offshore windfarms can also harm seabirds where these activities overlap with critical seabird areas.

Metzger’s team at the Malta Seabird Project have been tracking the movements of Malta’s breeding seabirds to map important flyways, feeding areas, and other communal hangouts which need attention. Each EU country is responsible for protecting and managing marine habitats under the Natura2000 framework. In 2015, the LIFE+ Malta Seabird Project presented the areas around Malta on which Maltese breeding seabirds depend in various stages of their lives. Those that fall within Malta’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) will hopefully soon be incorporated into Malta’s Natura2000 network. But seabirds have no regard for national boundaries so their conservation depends on international research teams and intercontinental initiatives to halt threats.

Risks on land

| How to Follow Seabirds |

| Large-range at-sea movements are difficult or impossible to trace visually. Cutting edge technology can come to the rescue. Remote data loggers are relatively small devices that can be attached to animals and use one of a range of techniques to record their position. Device applications change depending on their size and weight, level of accuracy, and battery life. The smallest devices available use the time of sunrise and sunset to approximate seabirds’ position on the globe. The most accurate devices record GPS location via satellite connection. As data loggers continue to become smaller, more accurate, and cheaper, their applicability to new questions and smaller species increases. |

Let us have another look at coastal seabird colonies. Deserta Grande is much like an oversized Filfla—it is a 16km-long ridge of stratified volcanic rock and bays of loose boulder scree. Both islands are uninhabited nature reserves, with strict access control and negligible direct human disturbance. And both still belong to seabirds. The Bulwer’s petrel colony on Deserta Grande is probably the biggest in the Atlantic, much like how Filfla likely hosts the biggest population of Mediterranean Storm petrels in the world. If the quality of these land areas deteriorated, the populations could suffer a fatal blow. Shearwaters and petrels only approach their coastal breeding colonies under the cover of darkness to escape predation and harassment by gulls. However, the lighting up of promenades has exposed some cliff lines and made them unattractive to seabirds. Several historic breeding colonies in Malta have probably been abandoned because of light pollution. Chicks ready to fly the nest also wait for night-time to take off, unaided towards the horizon, but street lights can, instead, attract many fledglings to fly inland.

Alien invasive species are a huge threat on land, particularly on islands. Rats are the most notorious. With no natural predators in Malta, their numbers can quickly explode by feeding on our litter. Rats are intelligent, curious, and agile, and are able to swim several hundred metres. Their presence at breeding colonies spells disaster, as the rodents prey on eggs and chicks and can easily wipe out a breeding season.

Seabirds hold an important place in the food web and reflect the health of the seas in their success. Unfortunately they are also very vulnerable

But it is not all doom and gloom. It is now 2016, and as the LIFE+ Malta Seabird Project draws to an end, BirdLife Malta has just launched a new LIFE project—Arċipelagu Garnija—which will aim to protect birds on land. Metzger is now heading a fresh team to identify threats to the Yelkouan Shearwater colonies scattered across the Maltese Islands. Arċipelagu Garnija also wants to engage with the public and bring them on board. Small changes like not leaving litter for rats, reducing light pollution, and keeping sound disturbances low near colony sites will go a long way to help preserve seabird populations.

These ocean wanderers captivate me. They have attuned themselves to the ways of the seas for the past 35 million years. Now they are one of the most endangered groups of birds in the world. The only way to stop their disappearance is for worldwide research to go hand in hand with political and social willpower to make sure that seabirds keep shearing

the seas.

Members of the public can learn more about the Maltese Islands’ seabirds and enjoy them in their natural habitat during yearly pelagic trips organised by BirdLife Malta.

Marie Claire Gatt’s Master degree was partially funded by the Master it! Scholarship Scheme (Malta). This scholarship is part-financed by the European Union—European Social Fund (ESF) under Operational Programme II—Cohesion Policy 2007-2013, ‘Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality Of Life.’

Comments are closed for this article!