Parathletes challenge expectations and break boundaries. Some of them reach their peak performance relatively late in life. Strong-willed individuals also defy diagnoses and social norms, as members of Malta’s paralympic movement and para-sport experts tell Daiva Repeckaite and Shruti Sundaresan.

‘Ask anyone who knows me – losing is not in my dictionary,’ para swimmer Julian Bajada smiles. Various twists and turns in his life have only inspired him to take up new sporting challenges. Born with a rare condition affecting his limbs, teen Bajada couldn’t resist playing football with his mates between numerous surgeries. When he grew up to become a lawyer and athlete, he completed the Gozo-to-Malta challenge (a 6km swim) as a member of the National Maltese Para-Swimming Team, and took up rowing when he studied in Cambridge. His story resonates with those of numerous local and international parathletes, who juggle professional ambitions with demanding training schedules.

‘Inclusion meets Excellence,’ proclaims the motto of Malta Paralympic Committee (MPC), — a new para-sport structure officially affiliated with the International Paralympic Committee since 2018. ‘It’s fine if people with disabilities only engage in sports as a hobby,’ says Bajada, the committee’s secretary-general, emphasising the benefits sport has for health and self-confidence. Yet for him, these two concepts are essentially the same thing. ‘The primary purpose of every parathlete is seeking excellence — competitions abroad, representing your country, and the pinacle is the Paralympic Games. They show that there is no physical limit.’

‘Ask anyone who knows me – losing is not in my dictionary,’ – para swimmer Julian Bajada

In Disability in the Global Sport Arena, a book she edited, Canadian anthropologist Jill M. Le Clair wrote how reforms in the paralympic movement in the 1980s transformed its classification from disability-based to sport-based. This allowed athletes with different abilities to participate in the Games as members of one national team and shed stigmas prevalent in their societies — paralympians identify as high-performance athletes with disabilities, who exhibit exceptional physical strength.

‘When [people with disabilities] embark on a sport on a professional level, this will give them a new dimension to their professional lives. The emphasis is on the professional aspect. They can aim high and have dreams to succeed in a world that is so beautiful — which is sport,’ says University of Malta’s chemistry professor Joseph Grima, who presides over the MPC.

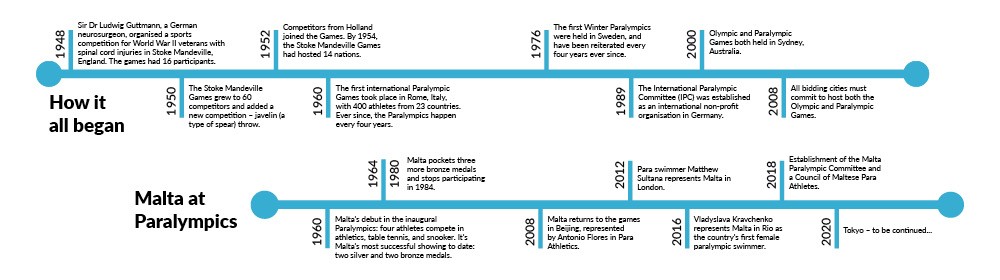

Malta has been participating in Paralympic Games ever since they started in 1960. The first entry was also Malta’s most successful. Over the years, Malta’s participation was intermittent, but its parathletes have brought home two silver and five bronze medals. In 2008, Malta returned to the Games with runner Antonio Flores, supported by physiotherapist Nathan Farrugia and sports coordinator Adelaide Silva, both working at Inspire.

Inspire is a non-profit that provides discounted rates to fitness enthusiasts with disabilities. ‘In Malta it wasn’t that common to see persons [with disabilities] involved in sport. Special Olympics caters for [those with intellectual disability] very well, but for physical disabilities there was a question mark. So people used to come here and ask to become involved in sport in an informal way,’ Silva remembers. After Flores, teenager Matthew Sultana competed in para-swimming, and four years later, Vladyslava Kravchenko represented Malta as its first female para-swimmer. According to Silva, para-sport enthusiasts decided that it’s time to convene a permanent committee to support parathletes between competitions.

The emphasis is on the professional aspect. They can aim high and have dreams to succeed in a world that is so beautiful — which is sport.

The Commissioner for the Rights of Persons with Disability, who initiated setting up of the new MPC, stresses the importance of movement and sport. He praises the Flexi Training Scheme, also known as the 20/20 scheme, which allows elite athletes to take time off work to strive for results. But much more needs to be done to make sure that athletes receive consistent and tailor-made support. Training coaches is particularly urgent. ‘Who would leave his or her job as a lawyer or accountant to take up coaching?’ Oliver Scicluna asks.

In its first year of operations, the MPC selected four para sport disciplines: swimming, athletics, archery, and wheelchair basketball. In their efforts to direct aspiring athletes to the right competitions for them, they will also have to guide them through the complex classification system that parathletes must adhere to. A qualified team assigns categories to all participants: ten different classes of physical impairment, plus visual impairment, and learning difficulty. This is for the sake of fairness, says Bajada: ‘A practical example is a double blade runner vs single blade runner, or a swimmer with no legs vs a swimmer with no arms.’ Not every sport discipline is available for each class.

According to numerous reports by the BBC, the classification created space for abuse in several countries, with athletes being artificially fatigued or misdiagnosed to be shifted to higher-severity classes to increase their chances at winning. Yet these instances from hyper-competitive environments feel distant to our interviewees in the tightly knit local paralympic movement. Currently, Maltese parathletes must be classified abroad.

The next challenge for MPC is to iron out the mechanism for recruiting and supporting parathletes as they train and go through international classification. Commissioner Scicluna emphasises that the next step will be to recruit professionals for MPC administration, as reliance on volunteers risks burning them out. ‘We are here to create the infrastructure,’ Grima says. He emphasises that supporting parathletes is about excellence and not charity: ‘These are real, very vigorous competitions with the same setup and infrastructure as the Olympic Games.’

Bajada concludes the committee’s vision: ‘We want to double the number of active parathletes every year.’ Meanwhile, the current torchbearers of the para-sport movement are striving for personal records — and radiating love for sport every day.

Interview with Vladyslava Kravchenko

‘I’m an accountant by day and athlete by night,’ says Vladyslava Kravchenko, who represented Malta in the 2016 Rio Paralympics in three swimming categories. She’s also a Malta Paralympic Committee member. ‘I hardly get time with friends or family, but one has to create a balance, find time for oneself… it’s really important,’ she says as we sit down in a Sliema cafe between other appointments she carefully clustered to save time.

In 2016, Kravchenko was Malta’s sole representative in the Paralympic Games and carried the Maltese flag at the inaugural ceremony. She was Malta’s first female swimmer at the Games. Malta hadn’t had a female Paralympian since 1980.

Born in Ukraine to a family of professional athletes, Kravchenko believes she was destined for sports, and started competing in rhythmic gymnastics. When her family moved to Malta in the early 2000s, the competitive element shifted aside, but she would still train.

As a teenager, Kravchenko suffered a spinal injury at a party, which resulted in paraplegia. Unable to return to gymnastics, she started swimming for her rehabilitation. ‘Somewhere during my recovery, I watched a documentary on the London Paralympics, and I just made up my mind to participate in the next edition,’ she remembers.

This kick-started her journey in competitive swimming. Her coach went to Istanbul to learn how to train parathletes, and soon she was competing internationally. For a year, Kravchenko also served as the European Paralympic Committee’s youth ambassador of Para Sport.

Apart from physical conditioning, Kravchenko emphasises mental strength. She likes to watch documentaries about leading athletes for inspiration and keeps in touch with fellow athletes, sharing tips and discussing issues. But not on social media. ‘I guess I am an extinct species — I don’t have any social media accounts apart from the public Facebook page which was set up during the Rio Paralympics,’ she smiles.

After the Rio Olympics in 2016, the experienced swimmer took up archery. ‘It’s all about prioritising,’ she says. ‘I know that I have to train 3–4 times a week and that is a priority, so everything else works around it. And thankfully, I work flexible hours, which allows me to train in the morning.’ While preparing for the Rio games, Kravchenko was part of the Flexi Training Scheme, allowing her to train for competitions while keeping her regular job.

‘The biggest motivation behind joining the [Malta Paralympic] Committee is my own journey. Athletes need support from the government, the sports sector, media, and [citizens]. Support has to come in for all [aspiring] athletes,’ she asserts. ‘In Malta, we have to work to provide the same amount of recognition and support to paralympic athletes as is given to Olympic athletes.’

Kravchenko wants to use her new role to bring more people into sport. ‘General awareness of the paralympics is very low. An ambitious goal for us is to reach out to schools,’ she says.

Rhythmic gymnastics, swimming, and now archery, there’s no stopping her. Ask her about the next sport challenge, and she immediately quips, ‘There are so many sports that I’d like to try, but right off the top of my head… skiing is on the bucket list’. Perhaps you’ll see Kravchenko zipping down an alpine slope this winter.

Interview with Antonio Flores

Maltese blade runner Antonio Flores has been competing internationally for almost 11 years now. Born with a clubfoot, he underwent corrective surgery at a very young age. ‘This surgery made it very difficult for me to participate in sports when I was younger. However, when I was around 14–15 [years old], we had a class race where I managed to come third without any prior training,’ he remembers. This success catalysed his future achievements.

Flores started looking for running clubs as a teenager, training with able-bodied athletes. ‘It was difficult, but I was still faster than the average individual training in other sports.’ He recounts how difficult it was, as there was no established body for paralympic athletes in Malta. The running enthusiast only learnt about paralympic competitions around the age of 17.

That discovery propelled Flores to many international competitions. In 2008 he participated in the Paralympics, which he remembers as ‘a magical experience’. He ran next to celebrated blade runner Oscar Pistorius, watched plenty of other sports, and met a swath of inspiring people.

‘At that time, I had both my legs,’ he mentions. ‘However, in 2010, while preparing for the London Olympics, I experienced severe pain in my foot and ankle.’ Pain made training difficult. His future in sport looked bleak. After extensive research, Flores, by then a trained podiatrist, took the difficult decision to amputate his non-functional foot: ‘To me, it was the most logical option’. He wanted to prioritise quality of life. The next challenge was finding a surgeon when other options were still being considered — a process which took months.

Finally Flores found a surgeon specialising in amputations. After the surgery Flores got a tattoo to celebrate his determination. The athlete benefitted from a free daily prosthesis, but raised the funds for a sports prosthesis himself. After recovery, he went back to his coach. ‘He has adapted very well, has a lot of patience with me, and [has done] a lot of research and training with a trial and error method, that has helped me immensely,’ Flores appreciates.

With the blade (leg prosthesis), he started off as a slow runner. Every session was more exhausting than the previous. But hard work, consistency, and persistence have kept him going. Flores takes inspiration from anime. ‘Most anime revolve around characters that beat the odds, go through problems, and overcome obstacles. This resonates with me,’ he says.

Along the way, Flores got married, graduated, and started working as a podiatrist. He trains six days a week to prepare for his next Paralympic Games. He intends to use the Flexi Training Scheme to reduce working hours when training. His amputation will mean that he will have to be reclassified and compete in the below-the-knee impairment with prosthesis category.

For being there for him along the way, Flores thanks his supportive family: ‘They were always highly encouraging and motivating.’ They found it difficult to accept the decision to amputate, but they modified Flores’ house for his needs.

Even a high achiever like Flores faces insensitive, prejudiced questions about his body. ‘The best way to treat a Paralympic athlete is to simply treat them as an athlete,’ he suggests. ‘Support us in the way you would support any national athlete.’

The Flexi Training Scheme by SportMalta allows athletes likely to represent Malta in international competitions to be compensated for the time they take off their job. More information about the scheme: for private sector employees and for public sector employees.

Comments are closed for this article!