Lockdowns, the Great Resignation, and an Anti-Work Movement

Jonathan Firbank investigates the conditions that led to the ‘Great Resignation’, where millions of people resigned throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. He discovers that it is less a consequence of an ‘anti-work movement’ and more a result of the mental health issues that workplaces can cause.

A World Paused

China initiated the first anti-COVID-19 lockdown in January 2020. As its effectiveness became evident, other countries started to follow in China’s footsteps, most using less draconian measures. Some countries resisted this economic disruption, but over time, it became clear that lockdowns were, at the time, the best defence against contagion. Within a year, most had followed suit; over half of the world’s population was in some form of state-mandated isolation.

In China and other developing countries, lockdowns threatened poverty. For most people, no work means no pay, and this could only be compounded by new expenses and the mental health burden that this new world placed upon them. But wealthier countries provided financial support, dramatically cushioning the blow these changes represented. Parts of these populations were deemed ‘essential workers’, struggling on in public-facing jobs that were now extremely dangerous. But as their lives worsened, lives for some ‘non-essential workers’ were actually getting better. They had time to reflect. The whole world was sick, but they felt healthier than before. Something must have been very wrong with how things were before.

Industrial Hours

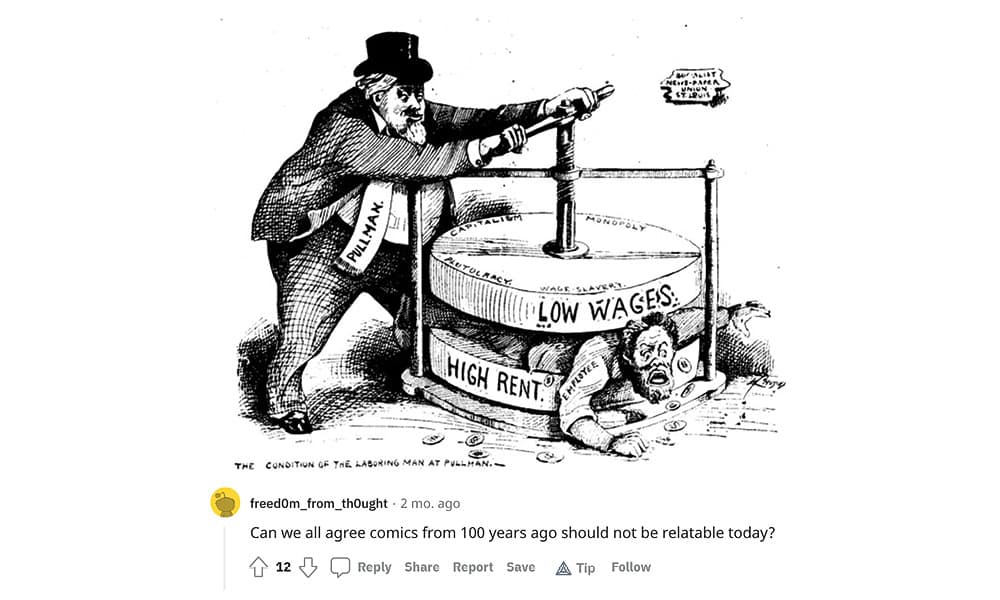

The working week as we know it today is a fairly new invention, pioneered in the industrial revolution as industrialists optimised the time they took from workers. The religious practice of not working on a Sunday gave workers a break, and eventually public outrage extended this into Saturday for many people.

A century later, a communications revolution meant employers could monopolise workers’ time when they were at home. Phone calls and emails haunted workers, keeping their minds at their jobs even during unpaid hours. Most recently, computerised adherence systems in entry-level jobs mean that whilst on shift, every second of a worker’s time can be monitored and databased. Amazon delivery drivers are tracked via satellite to make sure they don’t stop for too many rests. Call centre workers are humiliated by having toilet breaks timed and logged against their contracted hours. Shifts are staggered so employees can’t socialise with one another on breaks, which are kept to a sparse legal minimum.

And the reward for enduring this Kafkaesque nightmare? A legally minimum wage that does not keep up with inflation, forcing workers to choose between food and heating. The modern citizen finds themselves in a position where their entire life is spent, in the words of the great comedian Doug Stanhope, ‘working five to enjoy two’.

The Cost of Time

This is a bad deal. Workers’ time was sold at bargain prices, so employers bought as much as they could. But post-industrial capitalism is characterised by supply and demand more than by the working week. The supply of labour was already being impacted by ageing populations throughout the world. Lockdowns further restricted labour, and government relief gave workers options beyond returning to their regular jobs. Many amongst the working class were able to invest money for the first time, and crypto-currency exploded, creating overnight millionaires.

A comparatively tiny amount of people became rich from these experiments, but the new money flooding into markets inflated pension funds, enabling a swathe of people to take early retirement. But these financial windfalls don’t account for everyone who was handing in their notice. Work-related mental illness permeates modern society but often goes undiagnosed. Lockdowns gave some people a chance to feel well and caused them to hesitate when they were asked to return. A significant number of people sacrificed financial security in favour of their mental health after re-evaluating the worth of their time.

One of those people was a US citizen, Frank. His last name is withheld in case this article is used to sabotage future employment. He worked two entry-level jobs throughout the pandemic with progressively worse working conditions, until he finally quit for the sake of his mental well-being. The first employer is currently being investigated by Ohio state for malpractice that includes potentially illegal dismissals and attempts to withhold pay.

‘I can’t give certain details of the first job due to an NDA [a legally binding non-disclosure agreement]. Even while so many people were sick, we were told if we didn’t maintain profit margins throughout the pandemic we would be fired. I met this goal but was never paid my bonuses and then got fired anyway. There were no mask mandates. HR was meant to inform us if a colleague tested positive for Covid, but didn’t. Someone who normally sat next to me and someone who sat directly behind me both disappeared — they were sick with Covid but nobody notified me. When I figured it out on Tuesday and I wanted to get a test, a manager pulled me aside and asked me to wait until after work on Friday, presumably so they could keep me working. My life in the abstract mattered less than corporate productivity.’

Frank’s second job during the pandemic had far worse conditions. Frank found himself in an overtly bigoted workplace culture, where racist and homophobic slurs were used to describe customers. When his trainer discovered that Frank’s girlfriend was black, Frank overheard extreme, racist comments about him and his partner. He confronted his superior and quit immediately.

‘Why should I work myself to exhaustion and new mental-health lows to enrich people who, at best, don’t give a damn about me and at worst, actively exploit me?’

Frank chose unemployment over terrible working conditions. This wasn’t an easy decision to make: ‘A lot of employers feel that if somebody is unemployed there must be a problem with them. They don’t want to risk it. Every day is a struggle as more and more demands on money come at me. I’m going to have to get a job that I’m over-qualified for and doesn’t pay a living wage just so that I can go in the hole slower than I am now, and honestly, it all just makes me feel like I just shouldn’t bother.’

Clocking Out

People found that working from home was often healthier than spending their waking hours in the workplace. By working from home, they managed to strike a balance between their financial security and their own well-being. Yet there is an ongoing conflict between employees and employers over returning to the office. The prominent advocates for physically returning to work are managers, employers, or corporate-sponsored politicians, with no allies amongst groups concerned with workers’ welfare. In addition to the impact on mental health, commuting to an office directly reduces a worker’s wage thanks to the record-high cost of public transport and fuel, which is rising at a rate that has never been seen before.

Large institutions are slow to change the status-quo, and it’s difficult to remotely enforce extreme micromanagement. This hasn’t stopped employers from trying. Some home workers were forced to install ‘bossware’ on personal computers. ‘Bossware’ refers to software indistinguishable from remote access tools used to steal money from vulnerable people. It monitors screens, logs keystrokes, catalogs mouse movement, and occasionally activates cameras, microphones, and GPS.

But people were socialising remotely as well, sharing their working experiences and crowdsourcing ways to deal with them. ‘Bossware’’ demanded technical solutions, and these were provided by /r/antiwork, an anarchist community that exploded in popularity during lockdown. The once niche and cerebral community homogenised into a space to protest workplace culture as its user base grew to millions of people.

Mainstream media spotted this growth and created a narrative in which /r/antiwork was interwoven with what was dubbed the ‘Great Resignation’: a vast group of people that had collectively decided that they were being undervalued by employers. But reddit’s influence is vastly overestimated.

‘I don’t think that this is really a “movement” as much as it is work conditions, expectations, and the internet letting us share these experiences. Why should I work myself to exhaustion and new mental-health lows to enrich people who, at best, don’t give a damn about me and at worst, actively exploit me?’ says Frank

The truth is that there is no workers’ organisation big enough to account for the millions of people quitting throughout the pandemic. Attempts at wide-scale unionisation have been quickly crushed. Instead, the Great Resignation is due to millions of people making individual decisions. Many found their pay no longer compensated them fairly. Some found the money to stop going somewhere that harms them. Others were forced to resign by long-Covid or mental health issues. Some moved in with family. Some just reduced the time they were willing to sell. Some are searching for better work as this article is being written and will have rejoined the labour pool by the time you read it. Some simply retired.

The movement that created the Great Resignation was one that has thrived since the industrial revolution. A simple culture of employers maximising returns. Wages have decreased against inflation. Micromanagement and exploitation have been automated and optimised. Barriers to entry are higher than ever, but job security is increasingly rare. Working in these conditions should pay a premium. It took a global catastrophe for workers to realise it.

Comments are closed for this article!