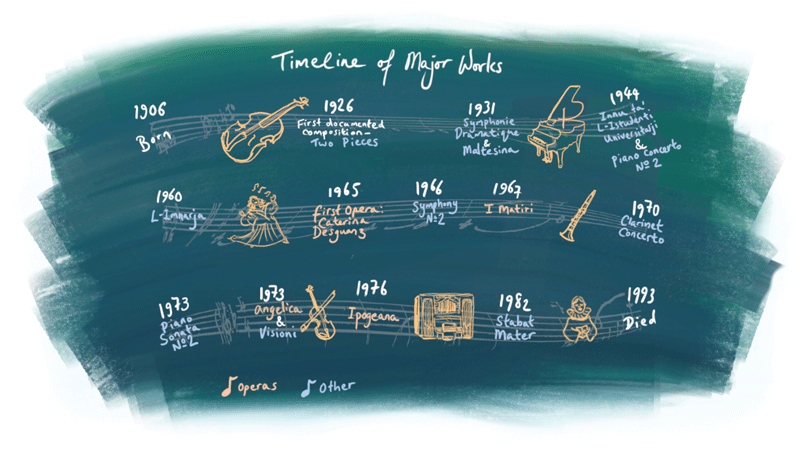

Maestro Carmelo Pace wrote over 500 compositions, survived WWII, taught Malta’s best contemporary musicians, and never left the island. Lydia Buttigieg (Ph.D. student at Durham University) writes about this elusive personality who shaped Malta’s musical landscape. Illustrations by Sonya Hallett.

For a small Mediterranean island, Malta possesses many eminent composers. One of the most prominent was Maestro Carmelo Pace who left a legacy of musical compositions. I studied his musical language and career. I also ask myself if he had some degree of autism. Can this idea be proved through his musical works or is it due to other reasons that his writing method remained mostly unchanged throughout his musical career? Despite his unchanging style he is considered to be a modern music composer when compared to his Maltese predecessors. Strangely, his writing does not seem to be have been influenced by the new experimental techniques emerging throughout Europe at the time.

A Maestro’s Life

Born at 4.15 a.m., 17 August 1906 in Valletta, Chevalier Maestro Carmelo Lorenzo Paolo Pace was the eldest of seven children. Living in the same household was his mother’s brother, Vincenzo Ciappara, a prominent composer, arranger, bandmaster, and a gifted viola player who highly influenced his nephew. Due to lack of documentation and resources we know relatively little about Pace’s musical education as a teenager and a young adult.

“He narrowly escaped death: a bomb directly hit his office”

The British Military bands stationed in Malta were his earliest experience of classical music. During frequent visits to his father’s workplace at the Commerce movie theatre in Valletta, Pace was captivated by the live music played by the resident quartet during silent films. Thanks to his uncle’s tutelage, Pace made good progress in his lessons, and at the age of 15 joined the orchestra of the Italian Opera Company at the Royal Opera House. Pace continued his studies for a further nine years under three foreign musicians who were resident on the island, but about whom nothing is known. Pace had lessons for the violin with Antonio Genova, violin and viola with Professor Carlo Fiamingo, and harmony, counterpoint, and composition with Dr Thomas Maine. According to his friend, the late Georgette Caffari, Pace never enhanced his musical studies abroad but continued to develop them independently. In 1921 Pace joined the conductor Carlo Diacono’s cappella di musica and by the age of 22 became section leader of the violas at the Italian Opera Company. By playing several different orchestral instruments Pace gained invaluable experience for his career. Despite this Ann Agnes Mousu, who interviewed Pace, said ‘Pace was displeased with irregular hours which left him with very little time for teaching music, a career which he had very much at heart: he did not wish to forfeit his love for composing either and therefore, he decided to quit’ — apparently in 1938.

With the onset of WWII, Pace was conscripted with the rest of Malta to the British Forces. After being found medically unfit for duty, he was appointed shelter supervisor in Valletta guarding about 600 homeless refugees. Pace later worked as a civilian clerk with the Royal Air Force; he deciphered allied aeroplane movement codes, which was a highly secretive exercise. Pace was permanently stationed in Valletta where attacks were constant. Over 3,000 air raids were registered over Malta. During one air raid Pace refused to leave his office to continue working. When he finally left he narrowly escaped death: a bomb directly hit his office soon after he left.

Due to his work and the onset of war, Pace stopped composing from 1940 to 1944. Despite this break he still conducted a small orchestra for the refugees. Pace also managed to teach music after office hours at the Command School of Education in South Street, Valletta. Pace, his wife and his family were forced to move house, from Merchant Street to Old Mint Street, after it was bombed.

As the War drifted to northern Europe, in 1944 Pace resumed composition with one of his works being the Innu ta’ L-Istudenti Universitarji (Hymn for University Students). The score is a short piece written in simple traditional harmony. Albert M. Cassola was the lyricist and it was soon chosen as the University’s official hymn after it won first prize in a national competition organised by the students themselves (the University Student’s Representative Council, today known as KSU).

From Folk Music To Virgin Sacrifices

Pace was a musical powerhouse, having penned around 550 works. They range from solo and chamber instrumental music to fully-fledged symphonies, operas, and concertos. Many have not been performed. Pace was the first national composer to collect Maltese folk rhythms. With the intent to preserve the island’s national identity, Pace composed Maltesina (1931), the first composition based on folk rhythms. Other folk music followed. However, Pace was well known for his choral work L-Imnarja (1960), an unaccompanied SATB choir (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, and Bass) written in the Maltese language, which was another attempt to retain the true identity of Malta’s musical heritage.

Pace also wrote four operas. They are considered to be the first fully-fledged Maltese stage works. Local critics praised them for their mastery of harmonic language and musicianship. Pace’s operas (which consist of a combination of mythological and historical events in Malta) are mostly directed towards a nationalistic style reflecting the country’s strong attachment with Europe. Hence Pace’s operas shed light on Malta’s historical background, composed for soloists, choir, and orchestra. The operas were all original works and not based on an existing literary work. Pace’s first opera Caterina Desguanez was written in 1965. The plot of the opera is based on a historical event which took place during the Great Siege of Malta in 1565, a battle between the Turks and the Maltese.

Two years later Pace wrote his second opera I Martiri (1967), a dramatisation of the rising of the Maltese against the French, who under Napoleon in 1798 took possession of the Islands without any serious opposition. However, when the Maltese began to feel oppressed they revolted against the French garrison. The French had to take refuge within the ramparts of Valletta where they remained besieged for almost two years, till they surrendered. During the siege a priest, Dun Mikiel Xerri, and others started organising a revolt within Valletta to attack the French, but unfortunately they were discovered and killed by a firing squad.

Two years later Pace wrote his second opera I Martiri (1967), a dramatisation of the rising of the Maltese against the French, who under Napoleon in 1798 took possession of the Islands without any serious opposition. However, when the Maltese began to feel oppressed they revolted against the French garrison. The French had to take refuge within the ramparts of Valletta where they remained besieged for almost two years, till they surrendered. During the siege a priest, Dun Mikiel Xerri, and others started organising a revolt within Valletta to attack the French, but unfortunately they were discovered and killed by a firing squad.

“the opera’s plot revives the time when beautiful girls used to be sacrificed to the gods”

The third opera — Angelica (1973) — is based on a fictitious story, though it is inspired by real events. In its history Malta was often invaded, its treasures robbed, and its people carried away as slaves. A slave in the Cumbo family, who converted to Christianity and was set free falls desperately in love with his master’s daughter. She, however, is to be wedded into the rich Manduca family. Haggi Muley reaches an agreement with the Pashà of Tripoli kidnapping the girl during her wedding ceremony and taking her to the Pashà. Notwithstanding the riches of his Harem, Angelica craves for her Maltese lover. Although she is finally liberated, her suffering leads to an early death.

His last opera — Ipogeana (1976) — is based on another fictitious story set in 1600 B.C. The libretto is set within the temple of Melkart and the surrounding countryside. Within its historical context the opera’s plot revives the time when beautiful girls used to be sacrificed to the gods. A tragedy emerges when the High Priest Brabani falls in love with one of the priestesses, Maħbuba. Brabani, who was considered by everyone to be a holy man, reveals his true nature at the end. Maħbuba kills Brabani pleasing the god Melkart who showers his people with rain and a good harvest.

Pace’s first composition takes his story back to 1926. The work, called Two Pieces, was written for a piano trio and transcribed in the same year for chamber work, followed by the violin and piano. The work was first performed in 15 October 1932 at the Juventus Domus in Sliema by an ensemble that included the Royal Opera House orchestra’s principal cellist Paul Carabott. Until Pace Maltese composers mostly wrote for ecclesiastical or liturgical functions, an approach Pace wanted to abandon. He ventured towards a more modernist style. Although Pace’s innovative approach was considered avant-garde in Malta for its harmonic language, the developments happening throughout the rest of Europe were not reflected in Pace’s work. Pace seems detached from other composers.

Pace’s advanced harmonic organisation changed Maltese chamber music from conventional harmonies to more experimental styles. Pace’s advanced musical works constitute contrasting links in their musical contours and tempo, and are unified by means of shared thematic material and harmonic connections of various kinds, such as the use of similar types of chordal structures (a harmonic set of three or more notes that is meant to be heard simultaneously). Typically of Pace, these connections can be extremely subtle and elusive; the music gives the impression of continuous improvisation, since the musical material undergoes continuous transformation and development. Pace’s first attempts at composing such avant-garde music was through his set of eleven string quartets. They were presented in a reclusive manner, reflecting his true character and emotional conflicts that continued to accumulate throughout his life.

In the early twentieth century, Pace turned his attention to string quartets. His predecessors never fully understood them. Pace’s quartets were scored from 1930 to 1938, with his last two written in 1970 and 1972. Unfortunately only one string quartet was ever performed — the String Quartet No. 2 (1931) premiered on 5 February 1965 in Waltham UK. Pace’s string quartets are structured on the classical three- or four-movement plan. He bestows excellent compositional techniques and has meticulous precision detailing each instrumental technique, phrasing, and dynamics. Many well-known musicians and composers considered Pace an exceptional technical composer. His compositional prowess sheds light on his turbulent emotional conflicts, while his obscure and dissonant harmonies reflect his reclusiveness, silence, and insecurity. Remarkably, his handling of instruments, sonorities, textures, and melodic contours remained consistent throughout his career, even when he composed two quartets after not having composed one for 32 years. His symphonies, concertos, and solo works also have a dissonant, obscure, harmonic language which remained stagnant in their musical approach, similar to that employed in his string quartets. Such works include Symphonie Dramatique (1931), Symphony No. 2 (1966), Piano Concerto No. 2 (1944), Clarinet Concerto (1970), Piano Sonata No. 2 (1973) and Visioni for solo violin (1973). Pace’s modernist works reflect a continuous trail of improvisatory ideas that are constantly being transformed into new rhythmic patterns, and constitute different tempos and textures. In these scores motivic segments (short musical motives extracted from main thematic material) occasionally appear and occur randomly throughout the movements. Most interestingly, Pace’s musical works appear unchanging (falling into three different stylistic genres) and keep the same compositional approach as that employed at the beginning of his musical career.

The Maestro’s Legacy

The Maestro’s Legacy

In my opinion, by examining Pace’s musical work, he could be considered as having some degree and form of autism. This is due to his restrictiveness and repetitive patterns presented in his musical works, coupled to an unchanging musical style and reclusive behaviour. Prof. Michael Fitzgerald at Trinity College (Dublin) suggests that Autism Spectrum Disorder is connected to creativity. People with autism can be highly focused and intelligent but do not fit into the school system, lack social skills, and are uncomfortable with eye contact. They can also be quite paranoid and oppositional, yet highly moral and ethical. Such persons could follow the same topic for 20 to 30 years without being distracted by other people’s opinion, and can produce in one lifetime the work of three or four people.

“In my opinion, he could be considered as having some degree and form of autism”

Although Pace has left a legacy of musical compositions, the circumstances of Maltese musical life hindered his creative development. His career illustrates the difficulties faced by modern composers working outside the major European cultural centres. Malta’s native musical traditions were lacking, meaning that audiences did not appreciate instrumental and new music. Audiences’ unchanging tastes prevented local composers from experimenting and developing a more modern style. Malta also lacked music professionals capable of performing complex modern works, a reason why his more stylistically interesting compositions were never performed in his lifetime. Pace must be one of the few composers who hardly ever heard what he wrote. It is extremely difficult for a composer to develop his artistic aptitudes if he does not have a chance to hear his own music performed at a good live performance. The nail in the coffin was Malta’s lack of musical infrastructure. He ended up working largely in isolation and in a critical vacuum. This could be another reason that explains his unchanging style, rather than having a form of Autism. We will probably never know for certain and till today, his musical output remains virtually unknown and unperformed.

Pace was one of the leading composers of his era. By the 1950s Pace was a well-established composer, musician and educator. His life was dedicated to composing and educating students in harmony, counterpoint and history of music. He did little else. His teaching reputation quickly spread and student numbers rapidly increased. His students ended up becoming leading musical theorists, composers, and conductors, their names much more familiar than Pace himself. Amongst his students were Prof. Charles Camilleri (one of Malta’s most famous composers who was also inspired by folk music and legends), Dr Albert Pace, Prof. Mro Dion Buhagiar, Prof. Mro Michael Laus, Mro Sigmund Mifsud, Mro Raymond Fenech, Moira Barbieri Azzopardi, and the late Maria Ghirlando. Many of his students have reached top positions in Malta’s musical sphere and superseded their teacher in fame and success.

After dedicating his entire life to music and teaching, Pace suddenly fell ill with pneumonia and died on the 20 May 1993. He left hundreds of unperformed works that are still to be heard.

The Maestro’s Legacy

The Maestro’s Legacy

Comments are closed for this article!