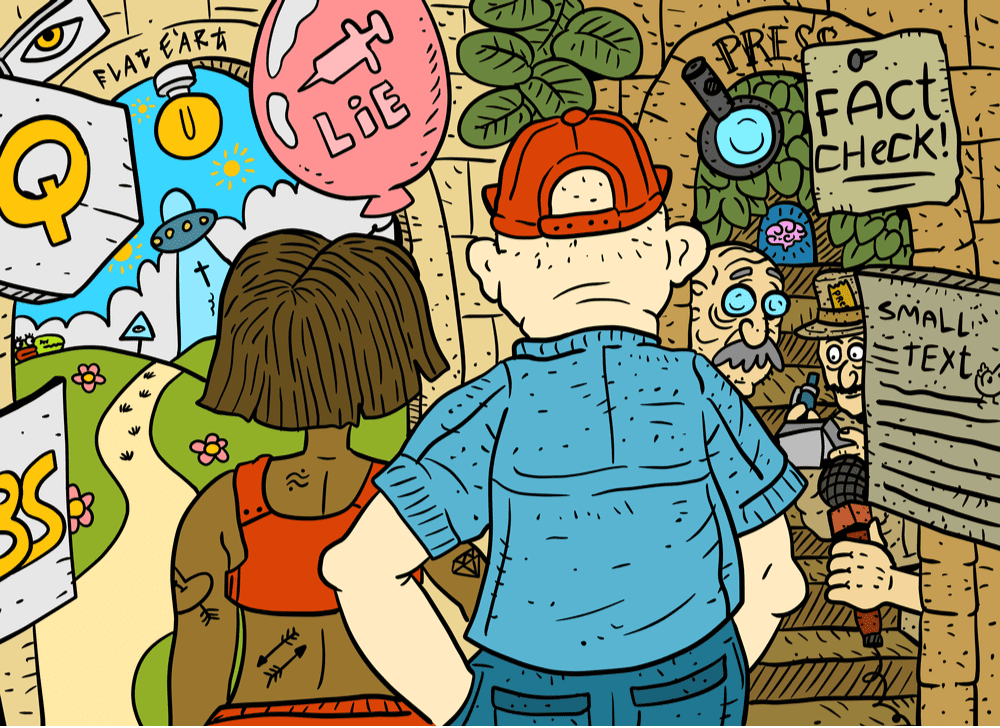

When times are hard, frustrated people question why. Conspiracy theories offer attractive answers, sometimes false and sometimes true. Andrew Firbank explores the psychology behind conspiracy theories: Why are they so enticing? What are the risks? And should they be challenged?

Beyond the public eye, powerful organisations are scheming to benefit themselves at the expense of others. This is, by definition, a conspiracy theory. Conspiracy theories are gaining a lot of traction these days, and it’s no wonder why. There is a web of contradictory information at our fingertips and a huge gap between those with power and those without. For people who are inclined or susceptible, it is easy to follow appealing narratives and draw extreme conclusions. But this can lead anywhere, from having controversial beliefs to commiting acts of terrorism.

Of course, conspiracy theories should not be entirely discounted. Systems of governance have let people down in the past. In 2002, for instance, an investigation by The Boston Globe helped expose systematic sexual abuse that had been concealed by the Catholic Church across the world. To think that this would be possible, both ethically and feasibly, may have seemed a wild theory before the evidence came out. It is a lesson that we are right to demand transparency from powerful institutions.

The drawback is when conspiracy theorists do not apply the same critical thinking to their own beliefs. Flat-Earth theorists deny that our planet is spherical but would get a shock if they questioned their own ideas with the same rigor. Recently, conspiracies also cast doubt on the Covid-19 vaccines and their true purpose. Whilst outlandish theories are easier to discount, even understandable fears, such as the vaccines being rushed into production, can often be calmed with further research. Similar coronaviruses have actually been studied for over 50 years, so we didn’t start from scratch, and an unprecedented global effort has created vaccines that pass pre-established safety standards.

What is real and what is fake?

So how should we approach new information? It is key to have an open and critical mind. Some people interpret having an open mind as accepting any unconventional belief, but this is not the case. Be open to considering new ideas, but properly challenge them before accepting them. Question where the information has come from, whether it has been accurately interpreted, and what motivations the speaker may have. Keep in mind that you are probably several steps from the information’s source, and each step can dilute the truth.

But for some, it seems they’ve already come to a conclusion. An aunt shares a post on social media about microchips in masks. A coworker implies that Bill Gates is a reptilian. It’s important to understand why people are drawn to conspiracy theories in the first place. Prof. Karen Douglas (University of Kent) points to three core psychological reasons: Epistemic – it’s easier to believe in something than to be uncertain; Existential – a desire for self-control, which can cause a rejection of mainstream narratives; Social – a need to maintain a positive image of one’s social groups, be they political, national, religious, or other. Conspiracy theories therefore shield people from unwanted truths. Perhaps the pandemic wasn’t a force of nature in a chaotic world, but was orchestrated by people who can be held to account. Perhaps your political party didn’t lose the election after all.

A study by Prof. Patrick Leman (Royal Holloway, University of London) also revealed that people instinctively link major events to major causes. In one of his scenarios, a president is shot and dies. In another, a president is shot and survives. The study participants were more likely to blame the first, more serious scenario on a conspiracy, although no extra evidence suggested as much. People may be seeking a balance in the natural world order when they attribute catastrophes to catastrophic plots.

Finding common ground

If you do know somebody who is a conspiracy theorist, it can be hard to know whether to discuss it with them or not. Trust is crucial for communication and persuasion, so you could be well positioned to reason with them if your relationship is strong. But effective communication goes both ways. Hastily dismissing that person’s beliefs may be harmful and counterproductive. Instead, encourage open and critical thinking. You already share common ground: skepticism. Use it fairly. Mainstream media and government officials may indeed have motives to distort the truth; explore these, and note the same applies to those who spread conspiracy theories. Sometimes a background check is all it takes to show that a conspiracy’s ‘insider’ source is nothing of the sort.

But there is a line that you do not need to cross. In his book The Limitations of the Open Mind, Prof. Jeremy Fantl (University of Calgary) argues that being equally open to all opinions can normalise or even perpetuate morally objectionable views. If somebody has fallen for a conspiracy theory that is too extreme for you to consider or debate in good faith, then it might be best not to. After all, it’s one thing to doubt new vaccine technologies and another to follow the white genocide theory. Sometimes the healthiest thing to do is to reevaluate your relationship with that person, or just agree to disagree.

Until we can achieve transparency in the actions of the elite, conspiracy theories are definitely here to stay. They offer appealing answers wrapped in powerful narratives. They can mislead people, spreading prejudice and harm, but they do stem from an understandable need for accountability in the face of hardship. To distill fact from fiction, it is crucial that we adopt and encourage open, critical ways of thinking. Skepticism is a healthy tool. Let’s not reserve it for opinions we dislike.

Further Reading

Boston Globe / Spotlight / Abuse in the Catholic Church. Archive.boston.com. (2004). Retrieved 6 July 2021, from https://archive.boston.com/globe/spotlight/abuse/documents/

Fantl, J. (2018) The Limitations of the Open Mind. Oxford University Press.

Comments are closed for this article!