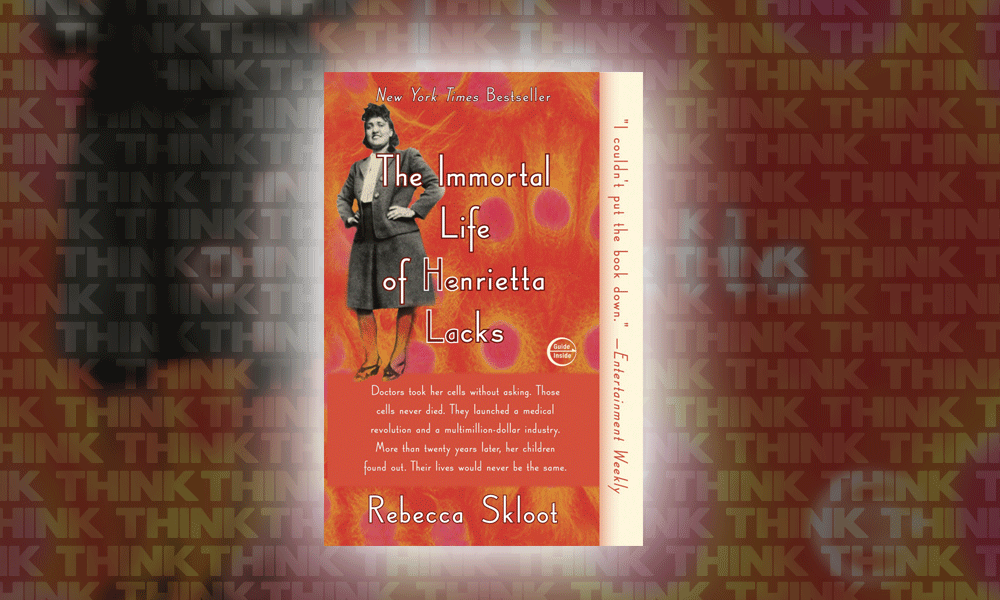

Over 60 Best Book of the Year lists, 75 weeks on the New York Best Sellers list, and several prestigious awards, The Immortal life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot is a must read for all. I don’t usually review 4-year old books, but this non-fiction book has it all: race and class issues, betrayal, loss, education and healthcare access, exploitation, and lucidly told science.

The book is a journey. A journey for Skloot, you can sense a certain naïvety and youthful enthusiasm at the beginning of the book that matures by its end. You also see a change in the people she meets, especially the family of Henrietta Lacks: some became close friends, others shunned her, others still ignored her then became her strongest allies in righting the wrong behind Henrietta’s life and beyond. Book proceeds helped Skloot set up the Henrietta Lacks Foundation to help her family and people in similar circumstances.

I met ‘HeLa’ before I met Henrietta. For my masters, I grew her cells to study a protein complex involved in cell division (cells dividing incorrectly leads to cancer) without knowing anything about her. I learnt about Henrietta before this book; my Ph.D. supervisor Prof. Margarete Heck passed around a one-page article about her with a moral tag line about one of the lowest ethical points in science.

Henrietta Lacks was an African-American woman who died on the 4 October, 1951 aged 31 from a very aggressive form of cervical cancer. The cancer was so aggressive that she died within months of her diagnosis at Johns Hopkins Hospital. That aggression made these cells special. Before she died, Dr Howard W. Jones took a sample of her cancer and passed it on to researcher George Otto Gey who, together with his wife Margaret Gey, successfully cultured Lack’s cells in a lab.

“The story is what I love about this book. Many popular science books are slaves to explaining really cool science, missing the point of storytelling”

Otto generously and freely distributed this first immortalised cell line popularising it around the world. Researchers used it to develop a polio vaccine protecting millions, to learn about how cells work, DNA functions, cancer, toxicity, and even AIDS. Companies commercialised it making countless millions from Henrietta’s cells with nearly 11,000 patents involving HeLa cells. Her family received neither notifications of these developments nor any royalties.

Yet even Skloot doesn’t demonise the scientists since back then the concept of informed consent was non-existent. It’s not even a question of race; Skloot admits that the scientists would have propagated the cells of a poor white woman in the same way. It’s a question of education and healthcare access, points still pertinent today.

The story is what I love about this book. Many popular science books are slaves to explaining really cool science, missing the point of storytelling. The best science books manage to balance these two qualities. Skloot goes one step further. To appreciate the story, she needs to tell you about the amazing scientific findings behind these cells. By learning the scientific background, the story becomes richer.

After this book, Skloot started tackling animals. Before science writing, Skloot was a veterinary technician. If you thought HeLa was an ethical mine field, animal research is much more explosive.

Comments are closed for this article!