Patients are currently monitored using wired leads (electrocardiographic cables). This decreases patient mobility and comfort. Studies have shown that it can also lead (pun not intended) to long-term skin damage, especially with newborns. A team of researchers from the University of Malta (UM) are examining whether some of this data can be extracted through digital cameras, removing the need for cables.

What if hospitals could use ordinary digital cameras to monitor patients’ vital signs?

While monitoring patients wirelessly sounds like an almost futuristic idea, it’s precisely the line of research being investigated by an interdisciplinary team of six scientists and medical professionals at the University of Malta and Mater Dei Hospital. The formidable team, consisting of Dr Owen Falzon, Prof. Ing. Kenneth Camilleri, Dr Abdelkader Helwan, Prof. Jean Calleja Agius, Dr Nicole Grech and Dr Stephen Sciberras, is currently spearheading what they call the NIVS Project: Non-Invasive Vital Signs monitoring project.

‘Monitoring vital signs like heart and respiratory rates is essential for various reasons,’ explains anaesthesia trainee Dr Nicole Grech over a coffee one morning. ‘It’s particularly important in wards like the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where patients are more likely to be unstable, so continuous monitoring can be a matter of life and death.’

Grech explains that heart and respiratory rates can often show that all is not well with a patient even when they are feeling fine; a situation that was quite common with COVID-19 patients over the past months for instance.

‘ECG monitor leads are considered the gold standard in terms of providing that data in real time, but they also come with a lot of issues,’ she explains. ‘First of all, there is a practicality issue, in that they tend to fall off patients and hamper their movement when they are trying to move about or even sleep. There are also issues when patients have hairy or moist skin, not to mention diseased skin that can become irritated or prevent the leads from adhering effectively.’

Grech goes on to explain that the leads can sometimes cause significant damage to the skin, particularly in premature babies, whose delicate skin could actually slough off when the adhesive leads are removed.

‘There is also a higher likelihood of infections spreading from one patient to another, regardless of how well these leads are disinfected. Hospital-transmitted infections are actually incredibly common, and they can lead to higher mortality rates, particularly in places like the ICU where patients are already vulnerable,’ Grech says.

The Word Health Organisation has prioritised research to find alternatives to contact-based devices such as monitoring leads. It wants to reduce antimicrobial resistance, which is a global and health development threat.

Finding new solutions

The spike in global interest and the recent focus on social distancing led project lead investigator Dr Owen Falzon to set up the multidisciplinary team and attack the issue with technical and clinical solutions.

‘The inter-faculty collaboration between UM and Mater Dei Hospital allowed us access to a full suite of equipment and resources, as well as the possibility to run tests in controlled conditions and clinical settings, to give us a much deeper understanding of the systems needed,’ Falzon explains.

Falzon, together with the Director of the UM’s Centre for Biomedical Cybernetics, Prof. Ing. Kenneth Camilleri, worked to synergise medical and scientific research, a step which has so far been uncommon in Malta. The team of researchers decided to dive into the concept of photoplethysmography (PPG), which operates on the idea that changes in someone’s heart rate can be detected through skin colour changes.

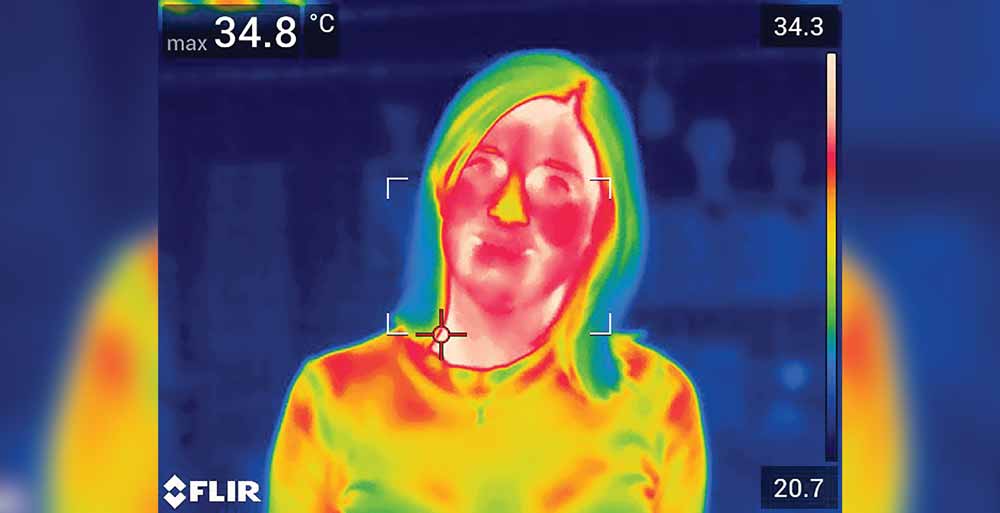

‘The basic idea is that every time the heart beats, it pumps freshly oxygenated blood — which is redder in colour — to the surface of the skin,’ explains Grech. ‘This gives the patient a pinker hue. The process is invisible to the naked eye, but a basic camera can pick up the subtle change.’

Grech goes on to explain that using a camera, known as remote PPG, would be non-invasive and would ultimately enhance patient wellbeing.’The absence of leads would mean that patients can move around in their beds without fear of getting disconnected or tangled. The risk of contamination and skin damage would be lowered, and the remote data collection would also allow for more effective physiotherapy sessions as patients need not be concerned about getting disconnected from monitors during these important sessions.’

What happens to the footage?

In the interest of this project, the team has already gathered around 44 hours of footage in total; first from healthy volunteers (approximately 31.5 hours) and then from ICU patients (approximately 12 hours). But how does that translate into medical data that health professionals can interpret?

Data analyst Dr Abdelkader Helwan explains that the data and videos are being fed into a convolutional neural network — a form of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that can learn how to carry out complicated tasks based on the data it is fed. Helwan will then work on creating an algorithm that allows the machine to recognise anomalies and irregularities in patient heart rates, in the same way an ECG monitor would.

Helwan explains that AI is becoming increasingly important in the health sector, with models successfully detecting and classifying diseases like skin cancer and beating experts at determining the malignancy of tumours.

‘Our work in this particular project is very robust as we are using various video scenarios, including a variety of poses, illuminations, and distances from the camera,’ he adds. ‘Filming patients in a hospital environment will allow our AI to better overcome common issues identified in this method of data collection.’

Some of the most common challenges to remote PPG have been highlighted in medical and research journals. From the placement of the equipment to data privacy issues, this research project is trying to overcome several challenges.

‘The camera itself can be a little cumbersome, so we need to think of where we can place the equipment to effectively monitor patients without disrupting the staff if we are to use this method in a real world setting,’ Grech explains.

‘Clinical tests have also thrown up issues like light changes causing a disruption to the data collected. If there are lights flashing from various monitors or pumps around the patient, the data may become muddled,’ explains Helwan. ‘Movements of hospital staff around the patient can also cause disruption to the data collection.’

Echoing Helwan, Grech explains that this research project collected data in dim light, bright light, and even darkness to train the AI to interpret data in as varied conditions as possible. The idea was to simulate real use.

Next steps

‘Beyond the practical aspects,’ says Grech, ‘our clinical tests have shown that we need to have a wider data set to compare to. The data collected from healthy patients often does not match up to the conditions of patients in wards like the ICU.’

‘The algorithm won’t be able to recognise patients whose heart rates are perhaps outside the normal zones, so we are currently applying for ethical approval to collect data from healthy patients doing exercise. This will allow the algorithm to develop an understanding of more elevated heart rates, for instance,’ she adds.

Data privacy is another key issue. Given that this data relates to patients with severe health issues, the team had to seek approval from Mater Dei Hospital and UM Ethical Committees to ensure that the data is secure, with only the clinical and research team having access.

A further hurdle the team came up against is the expensive nature of the equipment in question, with some of the machines costing thousands of euros. To this end, the team successfully applied for funding from the Malta Council for Science and Technology for the NIVS Project.

‘As mentioned earlier, we have already identified the need to analyse more elevated heart rates and feed it into the system, but the aim is to use all this data to assess the accuracy of the system and finally test it in a real-world setting,’ Grech adds.

The hope is for the research to ultimately become widely used in hospitals. The team have opted for a broader data set than has been attempted so far in any international study. Most studies around the subject have employed exclusionary criteria and focused on specific issues like patients undergoing haemodialysis treatment or preterm infants, but the local research team has chosen to have a broader variety of patients to properly test this form of data collection.

Intensive Care Consultant Dr Stephen Sciberras and the Head of UM’s Anatomy Department Prof. Jean Calleja Agius explains that the ambitiously wide data collection will allow the team to build an estimation model that should work seamlessly in a busy hospital setting.

‘The ICU offers the best opportunity to collect as much data as possible in a clinical situation, as it incorporates a wide variety of conditions,’ Sciberras explains. ‘Patients here can be awake or asleep, some could be breathing normally while others use ventilators, and so on… This ultimately means that the system will be better calibrated for everyday use, rather than only a specific type of patient.’

With infectious energy and optimism, the team has largely completed their data collection and are now well into the data analysis stage. Should these results be favourable, the project would likely change the image of hospitals as we know them and push them into a more contact-free future, a feeling that is entirely on-brand in our post-Covid world.

Author

-

Martina writes on a freelance basis for a number of publications including Think Magazine. She works in children’s publishing in London and has a background in journalism. Previous writing credits include MaltaToday and other other local content writing agencies. Her favourite topics to write about include lifestyle, culture and health issues. She also enjoys interviewing people and learning about new topics as part of her research. She holds an MA in Publishing and previously read for a BA in English at the UM. In her free-time, she can be found sipping tea in coffee shops, reading or trying out new hobbies.

View all posts

Comments are closed for this article!