Increasing GDP is often understood as a way of measuring economic progress. This overriding policy goal, however, is misplaced. Economic policies should ultimately serve societal interests, not the other way round. But making economic policies serve societal interests means rethinking what it actually means to live well.

How many times do we hear politicians lauding Malta’s economic growth as a self-evident sign of progress? Or that we need to make sure that ‘ir-rota tal-ekonomija tibqa’ ddur’ (the wheel of the economy keeps on spinning)? These sentiments are everywhere, yet rarely is the logic or implication of this thinking thoroughly questioned. There is not much point in economic growth if we do not know why we ‘need’ to keep on growing. Neither does it make sense to keep the wheel of the economy spinning if we do not know where it is going.

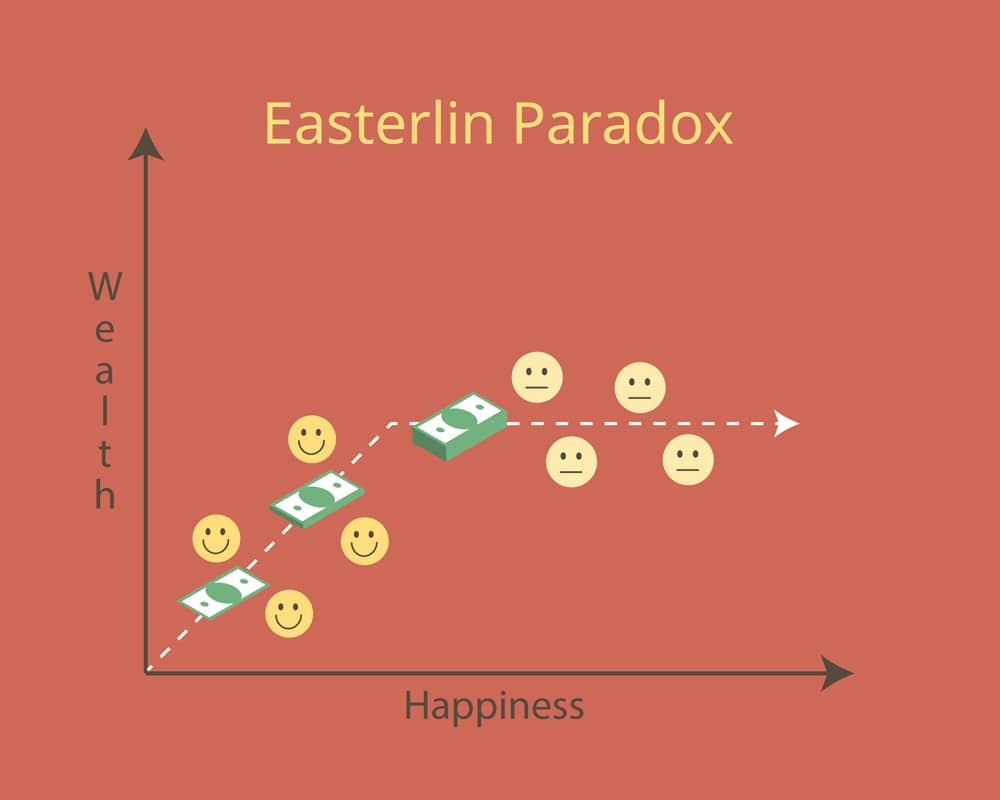

The use of the GDP metric as a universal standard has its origins in international development thinking that became consolidated and hegemonic in the 1950s. But the GDP metric is not, and was never intended to be, a general metric and indicator of well-being. Its inventor, the economist Simon Kuznets, specifically warned against using it in this sense. This is supported by studies that show that after a certain point, the relationship between economic growth and well-being breaks down. This phenomenon is known as the Easterlin paradox.

The Easterlin Paradox, or happiness-income paradox, is the observation that increasing economic growth does not contribute to an increase in happiness and well-being over the long term. Presumably, this is because once basic needs are met, increasing amounts of money become a way of signifying social status rather than addressing (often immaterial) things that actually contribute to one’s happiness and well-being. As such, as long as social and economic inequalities persist and widen, meaningful increases in well-being no longer remain possible. Ultimately, the Easterlin Paradox is only a paradox if one believes that increasing average incomes is – in and of itself – the key to happiness and well-being.

Many continue to use GDP as a concept interchangeable with wealth creation. This is justified to an extent, but little is said on how that wealth is created or where it is going. It makes no difference whether GDP is created from cutting down forests, property speculation, or alternatively, from healthcare and education. It also says nothing about whether that wealth is redistributed or captured by the already wealthy. In fact, the metric’s serious shortcomings as an indicator of well-being are already widely known, so it makes little sense as to why politicians still resort to it as a general indicator of progress and well-being.

Growing, but towards what?

Currently, society serves economic interests instead of the other way round.

The reason they do is actually quite simple. The existing economic system is dependent on economic growth for stability. This is a fundamental design flaw, as historically, economies were not dependent on growth at all. Surplus in pre- and non-capitalist societies was expended in ceremonies, rest, or communal celebrations. The Ancient Egyptians oriented their economies and societies for the afterlife, peasant societies around harvests, medieval societies in Europe around religion. Today, surplus is reinvested into the creation of more surplus, rather than towards any particularly meaningful goal. We need to be more deliberate in what economic activities we pursue and how we pursue them. This would reverse what the economic anthropologist Karl Polanyi identified as the relationship between the economy and society, where currently, society serves economic interests instead of the other way round.

There are other reasons why a growth economy is undesirable. An economy that keeps on growing is very difficult to decarbonise and make sustainable, as economic growth requires the use of more energy and resources. This means more infrastructure that needs to be built, more ecosystems that need to be destroyed for mining and extraction, and more land taken up for urbanisation and industrial production. This is all while trying to decarbonise an economy when its energy needs are still increasing. Given the growing urgency of the climate and ecological crisis, this is not a wise course of action.

Lastly, there is a deep and growing sense of social malaise, which is not possible to address simply through more growth. Growth does not come from thin air, but from labour and resources. Existing economic policies are leading to burn out, while increasing cost of living means that people need to work more for steadily diminishing returns. Meanwhile, we continue to ignore the importance of unpaid and invisible work that is essential to the healthy functioning of society. To continue to insist on more growth to solve these challenges is to try and solve them using the same logic that created them. We are – by pushing against both the ecological and social limits to growth – maintaining a system that is gradually undermining its own foundations.

What are the Alternatives?

Fortunately, there are much better ways of organising an economy. The Oxford economist Kate Raworth, for example, proposed a ‘doughnut’ economic model, which places many of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, within Johann Rockström’s planetary boundaries framework. Meanwhile, philosophies like buen vivir (‘good living’) in Latin America, ubuntu (‘humanity’) in southern Africa, and eco-swaraj (ecological democracy) in India have also been gaining traction, questioning the logic that growth is the key to prosperity.

Locally, we are seeing the first few steps in the right direction with increasing discussions on quality of life and some discussion on ‘Beyond GDP’ frameworks. Significantly, Dr Marie Briguglio has been working on developing well-being indicators for Malta, which has the potential to replace GDP as the measurement of progress.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, true wealth may be achieved not by continuing to grow an ever-larger pie, but by leaving the pie as it is and more fairly distributing what there is already.

Others have been working on an agenda under the banner of post-growth or, more provocatively, ‘degrowth’ economics, which would remove the growth dependency of the current economic model. These bring together a range of progressive proposals. Examples include the adoption of a Universal Basic Income and a job guarantee, a reduction in working hours and a 4-day work week, measures to create and strengthen participatory democracy as well as those that reduce car dependency, wealth redistribution, and limits on how much wealth and power one can accumulate. These are but a small sample of proposals that researchers believe could help achieve a post-growth economy. It is a pity that one of the most important economic questions of our time has largely been ignored by politicians and those with the power to make meaningful change.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, true wealth may be achieved not by continuing to grow an ever-larger pie, but by leaving the pie as it is and more fairly distributing what there is already. Thus, the question we should be asking isn’t ‘How do we keep the economy growing?’ but ‘What does it mean to live well?’ and ‘How can we orient our economy to achieve those goals?’.

Nothing in nature grows forever. It is time we acknowledge this fundamental rule. Like a fruit tree, we need to be able to know when and what we should grow, when we reach maturity, and when it is time to share our fruit with others.

Further Reading

Bergh, J. C. J. M. v. d. (2009). The GDP paradox. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(2), 117-135. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2008.12.001

Brockmann, H., Delhey, J., Welzel, C., & Yuan, H. (2009). The China Puzzle: Falling Happiness in a Rising Economy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(4), 387-405. Retrieved from CrossRef database. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10902-008-9095-4

Congressional Documents. (1934). National income, 1929-1932 : Letter from the acting secretary of commerce transmitting in response to Senate resolution no. 220 (72nd Cong.) a report on national income Federal Reserve Archive of Economic History.

Kubiszewski, I., Costanza, R., Franco, C., Lawn, P., Talberth, J., Jackson, T., et al. (2013). Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition, and Development : AJFAND, 93(5), 57-68. Retrieved from CrossRef database. Retrieved from https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.04.019

O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F., & Steinberger, J. K. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability, 1(2), 88-95. Retrieved from CrossRef database. Retrieved from https://explore.openaire.eu/search/publication?articleId=dedup_wf_001::15ddc574d2206e9cd76ae2f2bd297e02

Reyes-García, V., Babigumira, R., Pyhälä, A., Wunder, S., Zorondo-Rodríguez, F., & Angelsen, A. (2016). Subjective Wellbeing and Income: Empirical Patterns in the Rural Developing World. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(2), 773-791. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9608-2

Comments are closed for this article!