If it is true that philosophy is thinking about how we think, then the discipline’s characteristic scepticism and continuous self-questioning should also turn to the very mediation of philosophy.

Thinking philosophically, is not only a matter of carefully examining what we think about, but also how we organise and present ideas. Are written texts really the essential medium of philosophy? And assuming that this is the case, what kind of written text are we talking about? Writing comes in a variety of genres and styles. Is the essay format always the best fit for philosophical ideas?

Speculative fiction, as a case in point, is not often considered a legitimate form of philosophical (or academic) writing. And recognising that science fiction can occasionally be philosophical, does not necessarily entail that we believe that academic philosophy can be pursued through science fiction. The average philosopher arguably holds that their scholarly output consists in the linear exposition of rational arguments. From that standpoint, philosophical texts are generally expected to contain only small doses of storytelling, usually confined to illustrative examples.

Doing Philosophy through Sci-Fi

In a recent article of mine with Giacomo Pezzano titled ‘How to do Philosophy with Sci-fi‘, we reflect on the dominance of the theoretical essay in our professional practice. This institutional orientation is discussed as particularly baffling especially as the philosophical toolbox contains several ‘as-if’ kinds of devices and often relies on aspects of fictionality. I am referring, for instance, to cases like thought experiments, conception extenders, intuition pumps, and various elements of counterfactual reasoning. On what grounds do we then exclude fiction or other expressive forms in favour of impersonal, linear reports of findings?

In our article, Pezzano and I are not arguing that (Western) philosophy is now monolithically wedded to the theoretical essay format, or that it systematically dismissed other genres of writing throughout its history. While there is certainly a dominant institutional preference for the theoretical paper, our written canon clearly features a variety of textualities, from the Socratic dialogues to Nietzsche, to Kierkegaard and the existentialists, all the way down to Philosophy through Science Fiction Stories (by Helen De Cruz, Johan De Smedt, and Eric Schwitzgebel) and my own philosophical games. What we argued, instead, is the professionalisation of philosophy as an academic profession implicitly – and to some degree uncritically – adopted the format of the theoretical essay as its defining output.

Theoretical essays target a readership that is both professionally literate and conceived as purely rational subjects, and so expect to be informed through logical and dispassionate argumentation, rather than being personally and sensuously involved in a reading experience. What they need are insights and tools for the enterprise of writing more papers for other disembodied readers.

Believing that to be a philosopher requires writing these types of texts only is artificially limiting possible forms of expression and communicative reach. Accepting the idea that theoretical essays are the essential medium of philosophy also entails ignoring the fact that the history of the discipline already does feature almost all of the major recognised textual genres. While for most of the Western tradition the literary form of philosophical works was not assumed in advance, being a philosopher today requires one to embrace the theoretical paper or the theoretical monograph (an extended version of the essay). This conformism fosters a ‘monoculture’ of philosophical outputs, and inevitably encourages a kind of orthodoxy in philosophical though.

To be sure, our 2024 article does not condemn professionalisation and its evaluability, employability, and so on. Nevertheless, we argue that any process of knowledge institutionalisation needs to be wary of methodological conformism. Writing conventions should not become prescriptions that might invite epistemic injustice (exclusion or silencing). Having critiqued the dominance of the theoretical essay, I now turn to alternative philosophical writing by offering a few reflections on my own practice and my first-hand attempts to deviate from canonical, professional texts.

What We Owe the Dead

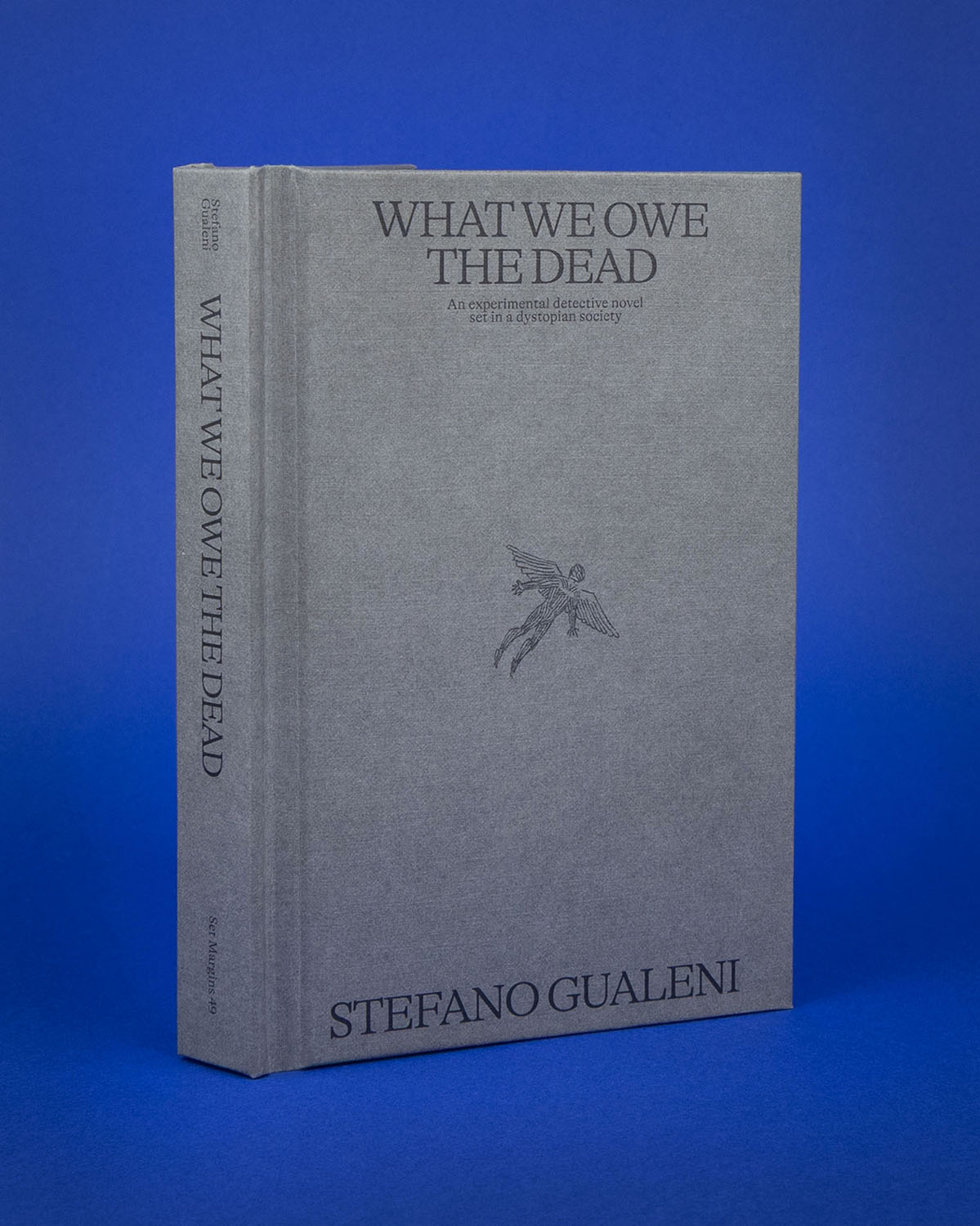

In an earlier THINK article, I presented my science-fiction novella The Clouds (Routledge, 2023) as an attempt at doing written philosophy in unconventional ways. The Clouds was discussed as an experimental case of hybrid philosophical textuality (leveraging fiction parts, essay components, and meta-philosophical bits). In a recently-published detective novel titled What We Owe the Dead, I have pushed to further exemplify the philosophical possibilities of fiction.

Like The Clouds, this new experiment in theory-fiction tries to creatively and effectively combine theory and fiction. Whereas The Clouds was an existential reflection on the simulation hypothesis (i.e. the possibility that we are living within an artificial subset of reality), What We Owe the Dead focuses on the survival of the human race in the aftermath of a future ecological catastrophe. Its sci-philosophical attention focuses on three themes:

- the personhood (both ethical and legal) of artificial intelligences,

- the philosophical and narrative uses of games within fictions, and

- our duties towards our predecessors (i.e. the titular ‘dead’).

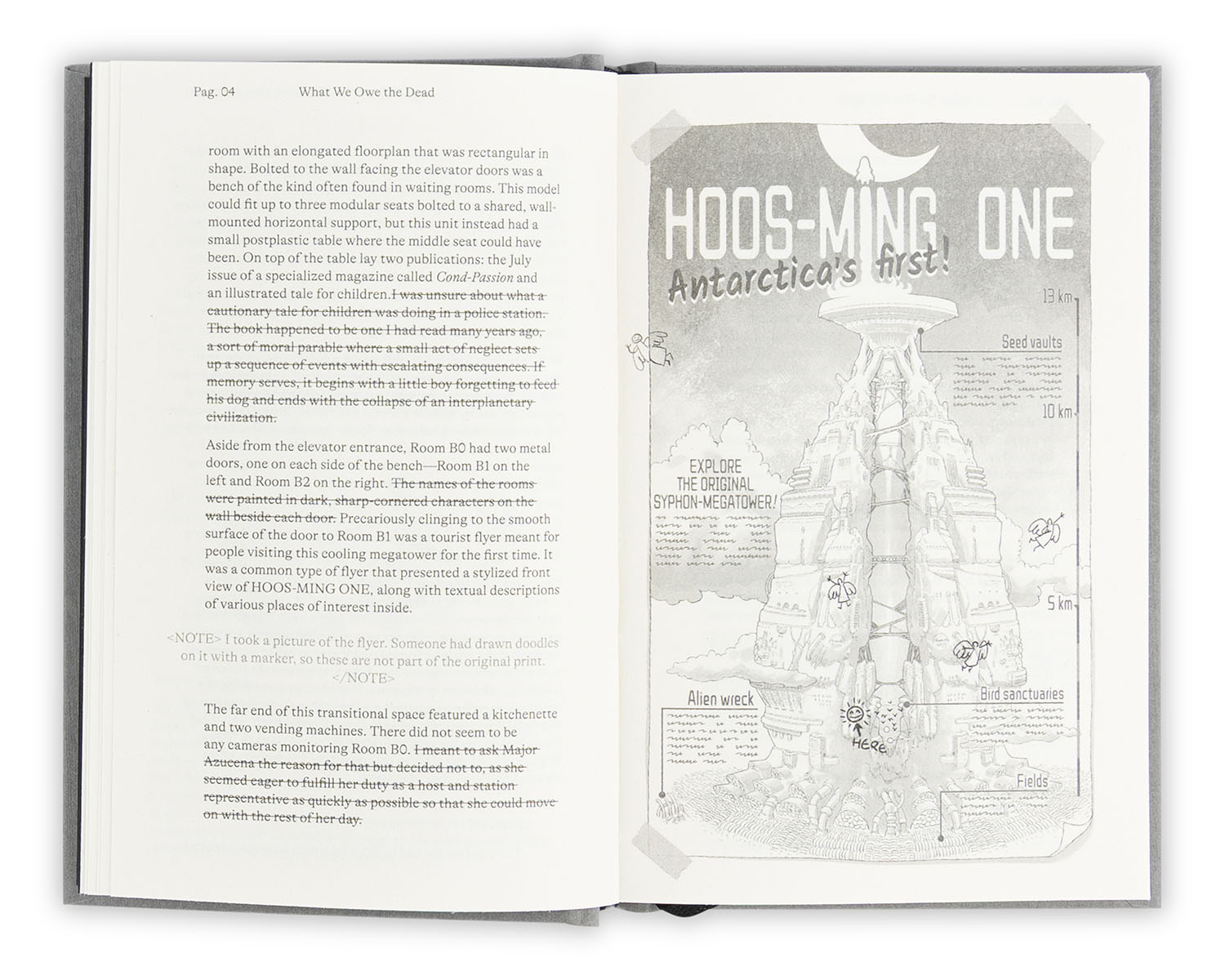

Central to the plot of What We Owe the Dead is the discovery of a strange board game of extra-terrestrial origin. My new attempt at philosophical fiction is not only about games but, in a loose sense, the novel itself is a sort of game. Peter Hutchinson wrote on the topic of literary play, encompassing both playful writing and the possibility of a ludic relationship between the author and the reader. In his 1983 text, Games Authors Play, Hutchinson suggests that ‘a literary game may be seen as any playful, self-conscious, and extended means by which an author stimulates his reader to deduce or to speculate, by which he encourages him to see a relationship between different parts of the text, or between the text and something extraneous to it’ (p. 14).

Curiously, Hutchinson did not claim that playfulness can be a catalyst for speculative philosophy nor that philosophy can itself be considered playful in nature. These are not only perspectives that I wholeheartedly embrace in my daily work as an academic philosopher, but are the specific beliefs that underpinned the whole project of What We Owe the Dead. The book, I believe, is evidently conceived as a playful and speculative experiment – an attempt to marry philosophical inquiry with narrative fiction. Through deliberate playfulness and structural ambiguity, it was written to challenge readers to engage with questions concerning personhood, mortality, duty ethics, and our existential relationship with technology and games.

Right: A glimpse at the Icarian cover of the Sci-Fi detective novel (Photo by Annette Behrens)

On 29 April, the author (Prof. Stefano Gualeni) will engage in a dialogue with Dr Daniel Vella and Prof. Krista Bonello Rutter Giappone in a free event where science fiction narrative intertwines with crises and questions of our time. Drawing on the book’s themes, the discussion will explore topics such as climate imagination, posthumanism, dystopian narratives, and the advantages and drawbacks of using fiction in academia (and as scholarly output). All details are available on Newspoint.

Book Launch: 29 April at 14:00, UM Library (Periodicals Study Space, Room 119)

Does What We Owe the Dead efficiently and meaningfully integrate theory and fiction? Does it invite a level of critical engagement comparable to the theoretical paper or the theoretical monograph? Will it manage to stimulate scholars and philosophy enthusiasts to re-evaluate their medium of expression? Whether this new experiment of mine succeeds in being properly philosophical, must leave it to the readers.

Follow the links to purchase a copy of The Clouds (Routledge, 2024) or What We Owe the Dead (Set Margins’, 2025) and decide for yourself!

Comments are closed for this article!