Patricia Camilleri meets up with Professor Henry Frendo to look behind the making of his new book Europe And Empire: Culture, Politics And Identity In Malta And The Mediterranean

“The book is a doorstopper” — Professor Henry Frendo didn’t altogether appreciate this comment. Of course, it was meant as a compliment since the book rigorously covers over 150 years of Malta’s history and two World wars — the events help to understand Malta’s current trials and triumphs.

What the author does in these twenty-two chapters is bring Malta to life. He creates the coordinates for an understanding not simply of the facts but how those facts have intertwined to make Malta’s past.

One of his aims was to achieve, “[…] a sustained critique of Colonialism” showing “Colonialism with regard to human rights and democracy and more”. Frendo is clearly concerned with examining what

Colonialism was in Malta and in the British Empire, especially in the Mediterranean. His narrative shows the personalities of the day within the context of Colonial rule and tries to explain what that rule meant.

is it legitimate to go on ‘blaming’ or ‘explaining’ things through Malta’s colonial paradigm?

How did these meanings influence the development of the islands’ politics, economy, and overall identity? Through these pages, the reader observes how the Maltese saw themselves over nearly two centuries of British rule. Frendo sustains that those two hundred years have left a mark on the Maltese identity and induced a modus operandi that is not easily changed. However, he also asks the question: is it legitimate to go on ‘blaming’ or ‘explaining’ things through Malta’s colonial paradigm? Clearly, what the Maltese were and what they are is important. It might also reflect Malta’s future.

The author has used his skill as a historian sleuth to access archives and libraries in at least six different countries (Tunis, Italy, UK, Malta, Australia and the USA). He was persuasive enough to receive very early access to the Fascist archive at the Farnesina in Rome. Historical evidence is found in official correspondence, the occasional personal letter discovered amongst the documents, dissertations, maps, photographic records, biographies, autobiographies, as well as documents provided by private individuals. The author also refers constantly to the local and international media, using vivid examples of cartoons and memorable extracts from the plethora of material available for the period. However, apart from his undoubted talent as a researcher, it is the skill with which Professor Frendo has translated those facts on to the page that has created a fascinating, eminently readable, and profound work.

The book spans the period from 1800 to 1964. The context is Malta as a Mediterranean island within the British Empire. Great Britain was present in the Mediterranean before it got involved with Malta and the first chapter sets the stage for that intervention. The whole period is studded with major events on the international scene which were happening outside Malta but which inevitably affected the islands. The panoply of protagonists ranges from significant governors to influential Bishops, from local politicians to foreign statesmen. Familiar names such as Manwel Dimech, Lord Strickland, Carmelo Borg Pisani, Nerik Mizzi and myriad others are all discussed with deep understanding. Frendo’s style engages the reader through constant reference to the social scene with examples of local culture and grassroots reactions.

One of the overriding themes is, inevitably, the ‘language question’. Frendo follows this thorny issue as it runs through the narrative like a leit motif, linking practically every aspect of the colonial period. The author examines the British language policy in other colonial contexts and clearly expresses the complexity of the ‘assimiliation-resistance’ paradigm. The analysis goes a long way to explaining why the issue still fills today’s newspaper columns and political discourse.

Ethnic identity among Maltese migrants is another of Frendo’s significant themes. He has published extensively on this issue. On this occasion, the author analyses how language, religion, and other factors impinged on the feelings of self-esteem and self-preservation amongst Maltese migrants in North Africa. He mainly achieves this through his close examination of the newspaper Melita, published in Sousse, Tunis in the 1930s.

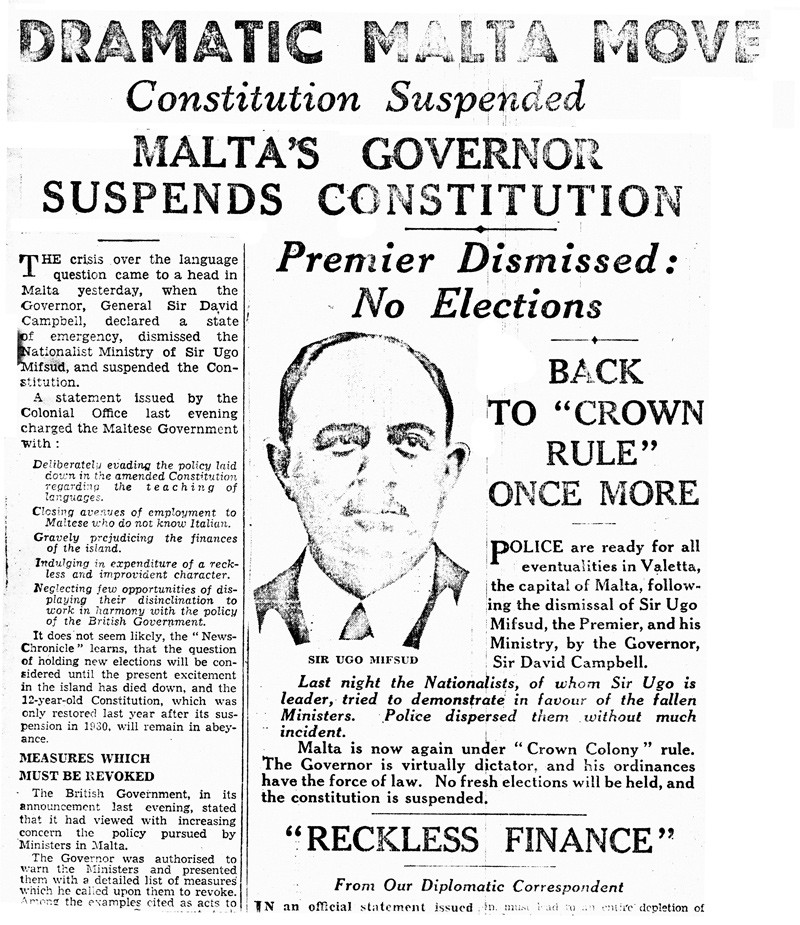

In the chapter ‘Strains in Anglo-Italian Relations in 1934’, Frendo traces the disintegration of those relations and its effect on Malta’s language culture. He discusses, amongst other issues, the last thrust by Sir Ugo Mifsud’s administration to maintain the teaching of Italian in elementary schools. He recounts how, in 1933, Governor Campbell ‘unequivocally refused’ to hold a vote in the legislative assembly on the matter. When, the legislative assembly passed a vote of confidence in the Mifsud administration, London simply dismissed the Cabinet. This action, coupled with others reducing the importance of Italian, sounded the death knell of the primary position of the language in Malta. For example, Italian was removed from entry exams to secondary school, and the law was changed making it unnecessary for notarial deeds and judicial proceedings. The final blow came in 1934 when the Letters Patent made English and Maltese the official languages of the colony.

Along with these serious reflections, Frendo also cites an excerpt from Johnnie Marks’s farce Il ‘Lingua Nostra’ performed in 1932 at Teatru San Ġorġ, Bormla. The play satirizes, in a most amusing way, the use of Italian in judicial courts. Marks’s dialogue might bring a smile to our face but the chapter entitled: ‘From Prison to Exile Without Charge’ certainly does not. The unforgettable events surrounding the exile in 1942 of a group of forty-seven Maltese, suspected of sympathising with the Italian cause, is clearly outlined with references to a wide range of writings on the subject. In the previous chapter, ‘The Clampdown on “Disloyalty” in Malta’, Frendo paints the background scenario in great detail, describing the events that led up to the decision. The list of deportees is fascinating as it includes people from very diverse backgrounds: amongst them well known personalities such as the Chief Justice Sir Arturo Mercieca, Vincenzo Bonello and Herbert Ganado as well as members of the Latteo family who worked in the food market and in a travel agency, and the Laudi brothers, all dockyard fitters. Frendo asks searching questions about the motives behind the action and suggests avenues of investigation which are still unexplored.

“Colonialism imposed its control of the social production of wealth through military conquest and subsequent political dictatorship. But its most important area of domination was the moral universe of the colonized, through culture, of how people perceived themselves and their relation to the world.”

wa Thiongo’o Ngugi, Decolonising the Mind (1986)

His well-researched pages remind us that history ‘as we remember it’ is not a viable option if a country — any country — is trying to understand the complex issues within society: identity, vision for the future, legacy, ethics, or human rights. Facile, emotional historical attachments linked to powerful and very immediate media interaction must surely be a recipe for a mis-reading and mis-understanding of society’s present. In the words of Simon Shama, paraphrasing Cicero: ‘to know our past is to grow up’. This is where university scholarship assumes a crucial role in the public domain. This is also where the study of the humanities becomes a vital tool for self-understanding and community in the search for truth and its interpretation. Although elements of universality are pervasive in human history, Frendo believes in analyzing diversity as well as the individual’s contribution to the big picture. After all, this is what history and especially ‘nation building’ is about.

Comments are closed for this article!