Digital archives safeguard our shared heritage, but in an era of cyber threats and fleeting information, who will protect these modern Libraries of Alexandria? THINK speaks to Dr Charlie Abela and Luke Brincat.

Did you know that the internet is only just over 30 years old? That’s right, the internet was made public in 1993. As someone barely over 30 myself, I still remember the screeches of dial-up internet and watching the blue loading bar until a page renders. The internet in the early nineties was a different beast entirely. It was a digital wild west with no sign of commercialisation, riddled with slow loading times, dodgy chatrooms, invasive pop-ups, and obscure blogs or websites passed around by word of mouth or chain mail. It was wonderful. And a part of humanity’s cultural heritage. But how much of this digital heritage will still exist a decade from now?

In the spirit of the early internet, individuals and organisations have banded together to preserve our digital heritage. Internet Archive, for example, is a digital archive that preserves over 916 billion web pages, 26 million movies and audio items (including about 270,000 live concerts), 43 million texts, and over 1.2 million software items. Project Gutenberg, one of the oldest digital libraries, focuses on free access to books in the public domain. It’s a great resource for classical literature, with thousands of digitised texts. Not to mention the various other archives, museums, and libraries (including at UM) that have digitised their content for broader access. These digital archives ensure that our heritage will remain accessible for decades to come.

The Value of Digital Archives

Not all digital archives are as massive as Internet Archive. Yet, every website, every company, and every person (even you, dear reader) has a digital archive of some description. The photos on your Google Drive are a digital archive of your personal history, and while not many people might actually care about your blurry photos of a night out, they are still valuable to you.

When it comes to more conventional archives, ‘you have archives whose value comes from the historical information stored in that archive,’ explains Dr Charlie Abela, senior lecturer of AI at UM. ‘The notarial archives in Valletta which are managed by the Notarial Archives Foundation, for example, are rich because they recount our history, but they are also valuable from a legal perspective as they serve as a legal record, giving traceability.’ Anyone who has tried to buy property locally will know first-hand why such archives are important – amongst other things, they ensure the land you’re buying actually belongs to the seller! This also ties into a recent project that Abela and his team are working on: Notarypedia. ‘We have a prototype, which extracts data from historical notarial documents, some even dating back to the 1500s.’ Such an archive could prove invaluable to notaries and anyone looking to buy or expand their property. Beyond this practical quality, these archives are historical and acts as a treasure trove of information about the way that our predecessors conducted their lives.

Another example of a digital archive is emails. Need to find your employment contract from 10 years ago? It’s there, saved as an attachment. Or maybe you want a record of when you started working on a project, or your CV; it’s all there. But, thinking on a broader scale, the emails sent and received by a head of state or other prominent figures may be today’s equivalent of a letter. ‘Previously, the state archives would keep letters of correspondence between heads of state. Now it is all digital, and it’s happening so fast,’ explains Luke Brincat, head of the Digitising Unit at the UM Library.

The Challenge of Digitisation

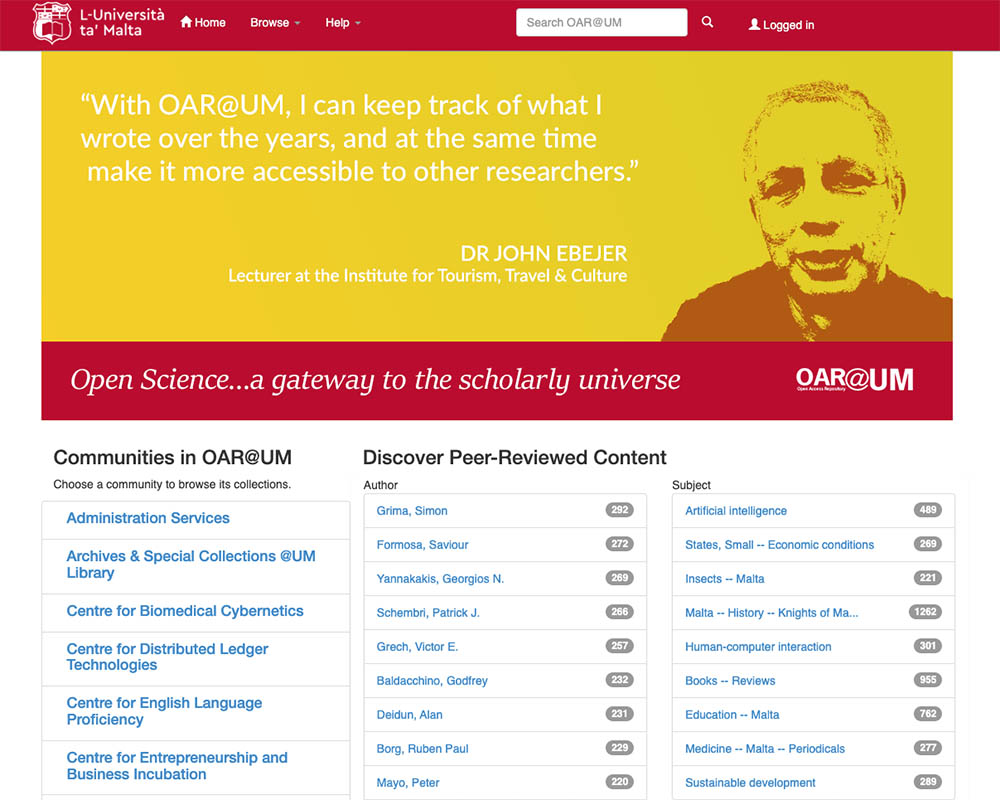

The Digitising Unit at UM is quite a recent addition, founded in June 2024. While the UM Library began its digitisation efforts a decade earlier with the launch of the OAR@UM platform in 2014, the creation of the Digitisation Unit marked a significant step forward. Its primary focus is on digitising out-of-copyright archival materials, among other key collections. ‘Our mission is to preserve and enhance the UM Library’s collection by converting physical materials into high-quality digital formats, supporting research, education, and institutional memory through comprehensive digitisation projects,’ explains Brincat proudly.

Libraries, knowledge institutions, and archives are a bulwark against the tide of misinformation. Researchers use these services because they trust the collections. ‘They place trust that if an article, or book, is held at that institution, then there is some credibility. There is an element of scrutiny when it comes to building a collection, whether digital or physical,’ he says.

But with the vast amounts of data being generated, the question becomes what to archive and how to archive. Where do you store digital copies? Using a cloud or third-party service? How do you ensure that that service is safe? Now imagine trying to archive the entire internet since its inception in 1993.

Despite the challenge, the Internet Archive works at preserving our global heritage, serving as our collective memory of the entire Internet. ‘On their scale, they are not just digitising information from one country, but on an international level. They are breaking the barriers of access,’ explains Luke. ‘With physical archives, there were numerous barriers to gaining access and ultimately interacting with the actual document. Now, with mass digitisation, these barriers are practically non-existent.’

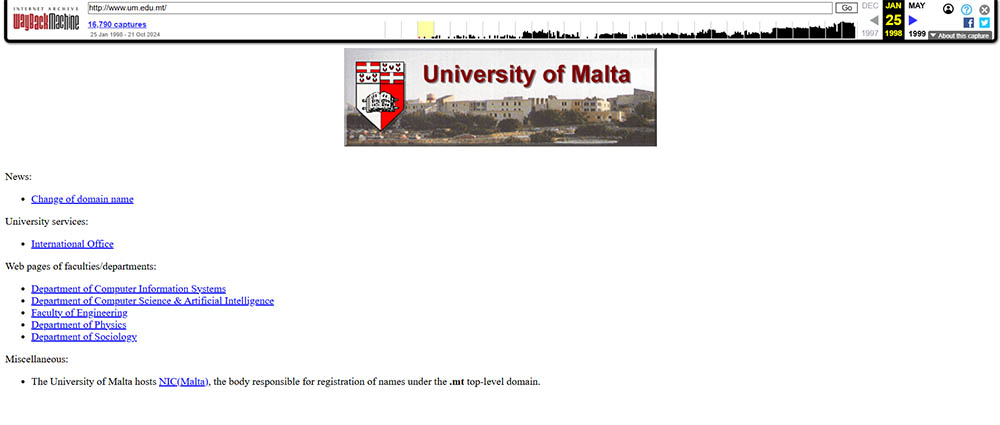

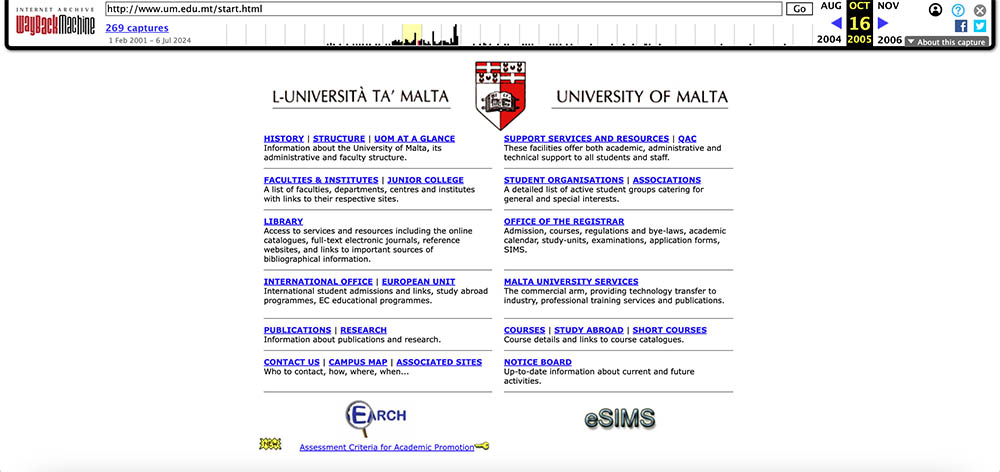

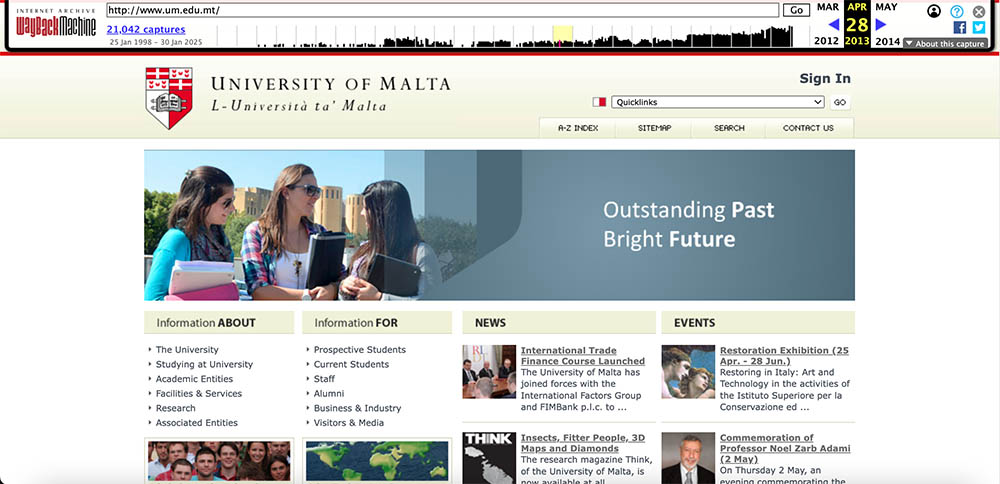

Take a look at how the University of Malta’s homepage transformed over the years:

Interestingly, you may spot the notice on the change of the UM domain name which was previously unimt.mt (now um.edu.mt)

Did you spot the eSIMS popup at the bottom? That was the first recorded time it appeared on the UM homepage as it was first introduced for the 2005/2006 academic year.

At this point, THINK was still in its early days, in fact, pictured is the cover of Issue 3

Protecting Our Heritage Against Cyber Threats

Last October, Internet Archive suffered multiple hacks. Unfortunately, this is not an isolated incident. Several cultural institutes have recently suffered cybersecurity attacks: London Public Library (December 2023), Calgary Public Library (October 2024), and the British Colombia Library (April 2024). Why are digital libraries and archives being attacked?

‘When a country or an institution loses their prized collection, it loses its identity. Judging by these attacks, we should look into securing and maintaining secure access to our collections,’ says Luke. ‘We put a lot of effort and emphasis to ensure that our money is safe. In a comparable manner, we need to ensure that even our history is maintained safely,’ explains Abela.

‘Even something as innocuous as an eServices Government portal has a digital archive. While we hardly think twice about them, there are troves of personal information – employee details, accounts, email addresses, and possibly even personal payment details are also saved,’ Abela continues. This data can be used for nefarious purposes, such as fraud, theft, or even sold on the dark web. Oftentimes, irrespective of the level of security protecting such Government portals (handled by MITA, locally), they are still tempting targets. Funding to have the most advanced cybersecurity technologies is fundamental.

Grand and prestigious institutions, such as the Louvre, Uffizi Gallery, or the British Museum might afford high-end cybersecurity systems to protect their databases, but smaller libraries, archives, and non-profits might not. Yet, the artefacts and knowledge held within these archives do not belong to just one nation; they are part of our shared human heritage. Just as the burning of the Library of Alexandria was a tragedy for humanity, digital initiatives such as the Internet Archive or Gutenberg Project, which have democratised access to knowledge, are equally important. Yet, these are run by non-profits, which begs the question: who is responsible for protecting these digital archives and, by extension, our collective heritage?

Who Protects Our Digital Memory?

Typically, the content generator is responsible for maintaining a copy. For research projects, there are typically stipulations that the information needs to remain online for a specific amount of time. But what happens after?

‘I was involved in a research project a few years back in 2013,’ explains Abela. ‘We organised a summer school event and created a WordPress website to share information and accept applications. A few years later, after the project had finished, that website was no longer maintained and was therefore inaccessible. All content disappeared.’

This is not an isolated case. Pew Research Centre estimated that around 40% of the internet from 2013 no longer exists. Whether that’s obscure internet cartoons or flash games, cultural records like pre-Facebook social media platforms, or even research, it’s just *poof* gone. This can occur for many reasons: perhaps the website is no longer supported (as in Abela’s example), the page is deleted, or ownership of the domain is lost, as well as digital decay (or bit rot). Imagine wanting to verify what happened in the early 2010s during the Arab Spring. Live tweets as the story unfolded – lost. Emergency broadcasts or news articles – unavailable. In the future, we might want to see how people acted and posted during the pandemic or what an untrustworthy politician really said. Without some kind of initiative to preserve this information, we run the risk of blundering into the digital dark ages.

A few years ago, Google often included a link to a cached version of each webpage in its search results. So, if a website was down or had changed, users could use the cached link to see a saved ‘snapshot’ of the page as it appeared when Google last indexed it. Today, Google no longer shows cached links. Instead, it links to the Wayback Machine from the Internet Archive. There is an irony in how one of the world’s biggest companies utilises the work of a small non-profit. Perhaps these vandalising hacks, as inane as they are, highlight how precious digital archives are. Clearly, it is time to rethink how to protect and preserve our digital heritage.

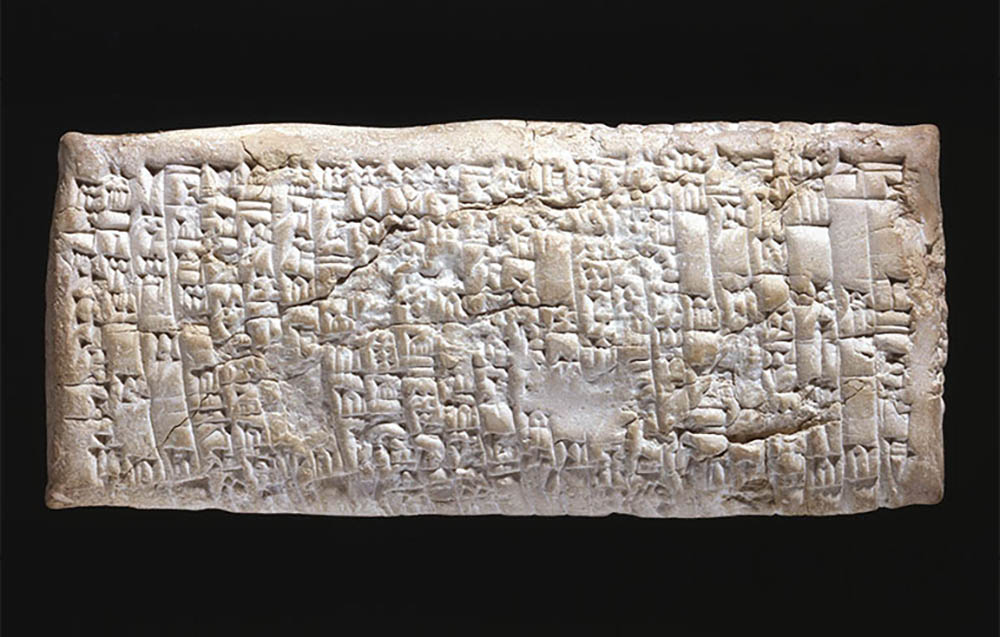

The digital is no less real than the physical. Our digital heritage is just as prestigious as the ancient scrolls and vellums of history. Online articles and papers are the key for future historians to understand the present. Internet memes are the digital equivalent of the vulgar (and comical) graffiti of Ancient Rome, and online product reviews are as fascinating to future archaeologists as the complaint tablet to Ea-nāṣir (the Babylonian Copper Merchant) for us. A memory lost online is no different than a book burned or a painting lost – the gap in knowledge and identity is the same.

A snippet from the oldest written customer complaint to Ea-nāṣir (the Babylonian Copper Merchant)

(Photo credit: British Museum)

Comments are closed for this article!