It is unlikely that Malta can ever become self-sufficient when it comes to food. The next best thing for the island is to guarantee sustainable food security. THINK sits with 4 experts to see how this could be possible.

Given the shocks to the global food supply chain witnessed during COVID-19, an increasingly unpredictable and uncertain world thanks to climate change, and the war in Ukraine, how does Malta fare when it comes to self-sustainability? Malta’s food production and energy security are amongst the many challenges the island faces today. Focusing on the theme of food and agriculture in particular, four academics from the University of Malta have offered their insights on these topics, to help guide Malta towards informed preparation and action.

Wheat Woes: A History of Food Scarcity

Food scarcity has been a longstanding issue in Malta, persisting for many years. Prof. Carmel Cassar (Director of the Institute of Maltase Studies, Chair of the Mediterranean Foodways Platform) states that the era of the Knights of St John was marked by food scarcity. He mentioned how a common phrase among the Maltese, “Malta qatt ma rrifjutat qamħ” (Malta has never refused grain), encapsulates how imported wheat was a cornerstone of the Maltese diet.

‘As described by historical records, like the Knight’s Commissions’ Report of 1524, Malta emerged as a “land of hunger.” Despite its fertile patches, the island could not sustain its burgeoning populace, leading to a heavy dependence on Sicilian wheat imports. Grand Masters consistently echoed their concerns in official documents, painting Malta as the “sterilissima isola” or the most sterile island,’ explains Cassar.

Malta could not have been selfsustainable in 1590, when it had a population of just 30,000 people. Even with modern farming advancements, feeding our current population of over half a million is impossible. British rule in the 1800’s shifted the geopolitical grainscape. Initially Malta imported duty-free Sicilian wheat, but this privilege was cut short by 1815 due to geopolitics. Cassar further states that the government monopoly, which kept the price of wheat under control, was lifted in 1822, causing changes in the types and quality of imported grain. Between 1828 and 1835, 82% of grain consumed in Malta was being imported. The bulk of grain was being sent from Southern Ukraine and the Black Sea coast, while cheaper and poorer quality wheat was also being imported from Egypt.

The British policy of free-trade did not improve the quality of bread and made the Maltese poorer. Prior to British colonisation, no duty was paid on imported wheat. However, due to free-trade, these subsidies were stopped which increased the price of bread. The situation only got worse in World War I with the closure of the Dardanelles by the Turkish Empire as wheat stopped reaching the Mediterranean from the Black Sea This was coupled with a shift in the importation of wheat from the not too distant Ukraine to the far-flung British Dominions, and brought about difficulties which resulted in the riots of 1919. By the mid-1920s wheat for the production of Maltese bread began to reach Malta mostly from the American continent. The history of Malta’s food supply is evidently one of shocks and vulnerabilities.

High wheat prices pushed the Maltese to turn to potatoes, which by the early twentieth century were being cultivated in relatively large quantities. They soon became a staple crop of Maltese agriculture and distinguished the diet of the rural poor from that of the urban population. While the latter used various forms of pasta, the former continued to make more use of potatoes.

Dr Rachel Radmilli (Member of the Mediterranean Foodways Platform – Mediterranean Institute at UM) emphasises that food (in)security is not a new reality. Past wars and current wars, such as the war in Ukraine, as well as critical events like pandemics, have triggered action to increase local food production. Geopolitics plays a critical role in food security.

Radmilli explains, ‘The islands used to import much of their food and fodder from Italy before the Second World War. When Italy joined the side of Germany, Malta, as a British colony, had to cut off all ties – including economic ties. Now, with the war in Ukraine, Russian military tactics have led to the specific targeting of grain provision facilities, impacting the country’s role as a leading breadbasket for much of Europe. Grain wars highlight weak spots in logistics and economic power games throughout the whole of Europe, as well as the fundamental problem that arises with over-specialisation. Islands as such tend to be particularly vulnerable territories.’

Addressing Today’s Challenges

Malta’s food security is naturally tied up in the survival and sustainability of local agriculture. Figures from the National Statistics Office show dwindling figures for local agriculture. The agricultural labour force decreased by 26.7% over a period of ten years, with a mere 13,341 persons engaged in 2020. In 2012, the annual volume of fruit and vegetables sold through the main organised markets was 2,694 tonnes (fruit) and 38,542 tonnes (vegetables) in both Malta and Gozo. In 2022, these figures dropped to 1,989 tonnes and 31,453 tonnes respectively. A similar trend can be seen with the number of livestock present on farms; with 45,209 pigs in 2012 to 29,554 pigs in 2022. This depends on a number of factors, and although these might be perceived as challenges, there are several opportunities within this sector.

Prof. Everaldo Attard (Director of the Institute of Earth Systems (IES)) points to the emergence of new technologies making precision agriculture possible. This will minimise the impacts on the environment in terms of the disruption of ecosystems, over extraction and need for water, and production of unwanted greenhouse gases.

Farmers are nowadays adopting artificial intelligence (AI) and alternative cultivation practices. ‘The IES is involved in a number of projects that explore such possibilities with farmers and producers. One such project, called IRRIGOPTIMAL, tackles water scarcity through the real-time collection of meteorological, soil, and plant data. Using this data, AI can monitor, predict, and control irrigation water needs for crops,’ explains Attard.

Attard states that the farming community is open to change. Perseverance from the local farming community and policymakers should go hand in hand to positively impact the Maltese agricultural industry.

Consequences for Nutrition

Food insecurity has become a challenge. Prof. Suzanne Piscopo (Professor of Health, Physical Education and Consumer Studies, Faculty of Education) defines food insecurity as both the insufficiency in the amount of food available to an individual, and the inadequacy in the nutritive value of the food to meet an individual’s needs.

‘The increase in different local NGOs who provide assistance through soup kitchens and food banks is perhaps testimony to a growing need for nourishment aid for individuals in different circumstances,’ points out Piscopo.

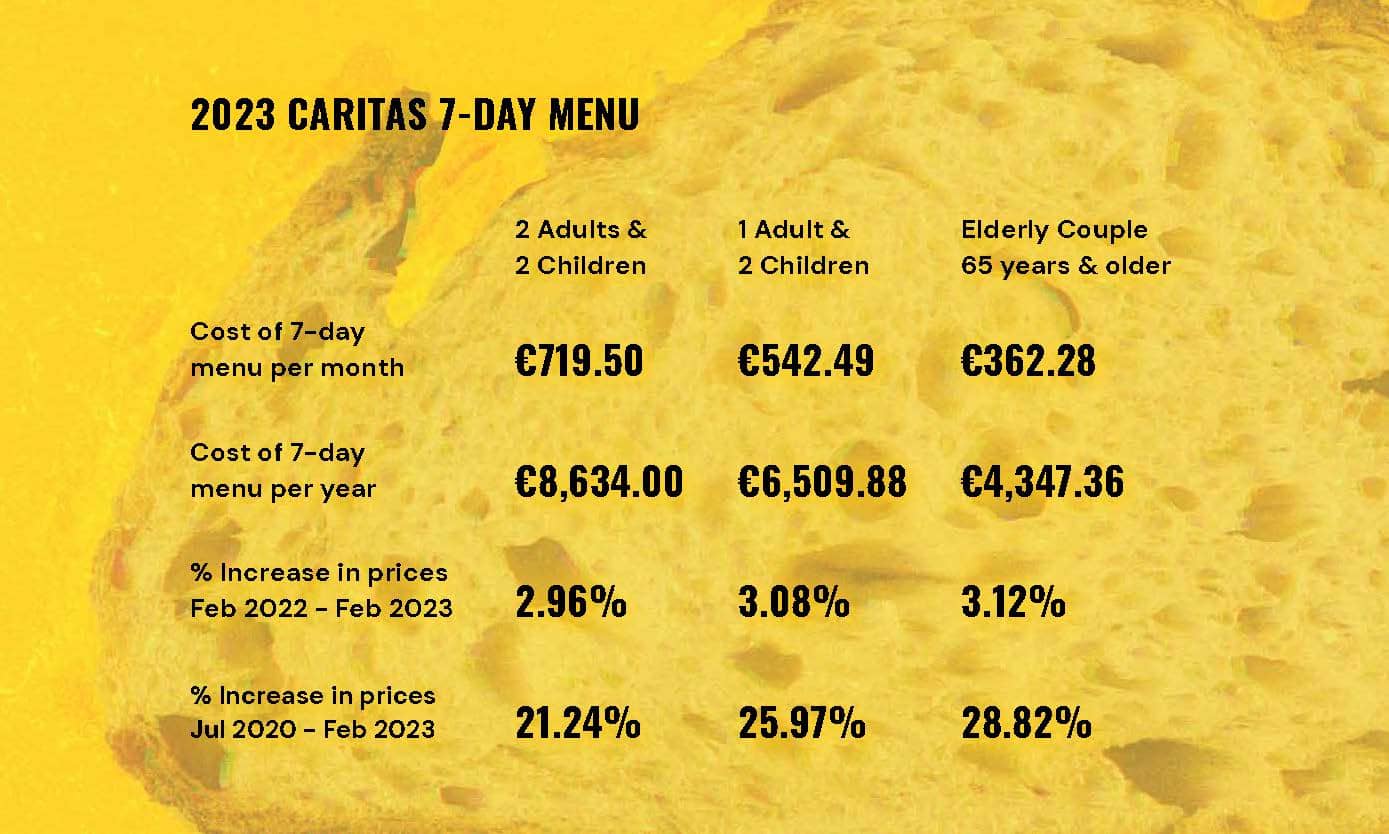

How do geopolitical factors and food insecurity directly affect the individual? To see how truly secure we are in terms of food, we need to see how it impacts some of the most vulnerable sectors of the population; low-income households. Piscopo recently led a study with Andre Bonello, on behalf of Caritas, to determine the cost of a 7-day menu consisting of 3 meals and 2 snacks per day which adhered to national dietary guidelines and certain sustainability criteria (such as local and seasonal food), and which offered value for money without compromising on healthiness. Compared to similar previous costing studies, this year also saw increases in the price of this menu. Thus, the 2023 Caritas 7-day menu offers policymakers a benchmark for the minimum cost required for the food security of three household types.

Increases in food prices may have an impact on both the types of foods bought by households, as well as where the foods are sourced from. Dietary shifts towards unhealthy food which is poor in nutrition evidently sets the paradigm for food security with this being as much about quality as it is about quantity. Targeted food and nutrition education efforts need to be stepped up, starting from pre-school children up to the elderly. Hands-on, budget-conscious and nutrient dense cookery for all children and teens through increased Home Economics classes, as well as community kitchens for low-income families and the elderly are just a few strategies which could help foster resilience and mitigate potential food insecurity.

While Malta cannot become self-sufficient, steps are drastically needed to reduce the country’s risks. A certain level of local supply should therefore always be maintained. Local agriculture must, however, in itself become more sustainable and environmentally friendly. Fortunately, action is being taken in this regard. On the consumer side, education is needed for more informed choices, both to support local agriculture and to avoid unhealthy choices driven by economic insecurity which will have an overall more detrimental long-term effect. While self-sufficiency might not be realisable, minimising food insecurity is an altogether more reachable target.

Acknowledgement

This article was prepared in collaboration with the Platform for Mediterranean Foodways. This platform draws in a specific interest in the study of food by placing it at the centre of a broader discussion on the socio-historic, cultural and scientific studies on the well-being and history of different Mediterranean societies, as well as of the Mediterranean region as a whole.

Comments are closed for this article!