Getting on the property ladder is incredibly difficult. Unless you are fortunate enough that your parents already own several properties, you will most likely be stuck for the rest of your adult life paying off your first (and possibly only) one-bedroom apartment. Is this grim future set in stone, or are there more creative solutions?

When I was younger, a friend of mine, let’s call him Frank, proposed an idea that has since then lived rent-free inside my head. Frank posited the idea of gathering a small group of friends, pooling resources together and buying a block of flats or a large property together. Thanks to increased purchasing power, a group of trusted friends could buy something that individually would be impossible. Plus, you avoid playing the neighbour lottery and have your friends as neighbours. Win-win!

Effectively, what Frank was suggesting was a commune between friends. Rather than living within the traditional home dynamic of husband/wife/children, this type of commune would expand to incorporate a closer bond between friends/neighbours, creating a strong sense of community. Other alternative housing arrangements include intergenerational housing, where older and younger generations live in the same household, or housing co-operatives, in which members of a community or residential organisation collectively own and control their living spaces.

Beyond our borders, these alternative domiciles are more widespread. In her book, Home and Sexuality, The ‘Other’ Side of the Kitchen, Dr Rachael Scicluna (Visiting Lecturer with UM’s Faculty for the Built Environment) explores alternative domiciles in contemporary Britain. She notes, ‘Contemporary British home settings, especially in London, have moved beyond the boundaries of ethnicities and traditional domestic settings; they comprise of divorced families; interracial marriages; informal and formal household arrangements, such as same-sex unions, co-habitants, single parents, solo living, and shared households with non-kin.’

If we want to tackle the struggle of finding property in Malta, we need to start by re-examining what makes a home.

Leaving the Nest

In Malta, children typically move out of their parents’ house after marriage. Ranier Fsadni, (Assistant Lecturer from UM’s Anthropological Sciences) points out how getting married served as a major transition, almost a ‘liberation’ for the young couple. However, he also points out that, ‘following the 2008 economic recession, it was also the tendency for younger people both in Europe and the US, to keep living with their parents.’ The main issue here is the expense, whether people are thinking of buying a permanent home or a temporary one, a married couple will probably find it easier to secure a home (or a loan) than an individual.

Yet, it is much more common for young adults abroad to move out of their parents’ homes when they turn 18. One of the main reasons is that students might leave to study at a live-in campus for example. In Malta, there is no need for a live-in campus for local students since UM is easy to get to. However, studying at University is not the only reason young adults abroad are more likely to move out compared to their local counterparts. ‘Pooling resources and living together is common in the EU. It ties to the rise of the singleton (a single individual living alone), and you’ve long had that in Germany, for example,’ explains Fsadni.

A Closer Look at Vienna

Casting our gaze towards mainland Europe might offer a glimpse into housing practices that could alleviate our local difficulties. The Austrian capital of Vienna has become the world’s most liveable city. In a recent article, The Guardian interviews a 26-year-old master’s student who, for barely €600 a month, lives in a 54sq metre, two-bedroom apartment, a mere 10 minutes from the central station. Such prices are absolutely unheard of locally. Furthermore, the master’s student did not need to put down a deposit and their rental contract is unlimited. How is this possible?

‘Vienna has a policy where the municipality owns the property and rents them out, and what it tries for is a mix of residents in terms of means, while others would be subsidised. It sees this as a way of being antispeculative,’ explains Fsadni. It is important to note, that these properties do not tend to have the stigma of poverty and crime associated with social housing. To do so, the city aims to mix people from different backgrounds and on different incomes in the same estates.

Such a system is hardly perfect and has its flaws, including debt issues. Furthermore, as the city owns a large swathe of property, repairs and damages can take a long time to be carried out. And, simply because such a system works in Vienna, does not necessarily mean it would turn out the same way locally. Yet, there are lessons that can and should be learned, such as introducing antispeculative measures with regard to property and moving away from private developers towards something like a cooperative.

Alternative Housing

Moving away from the current property model of having predominately private developers might just be the key to addressing Malta’s housing issues. Take a cooperative, for example, in which building blocks are typically owned by the state or the non-profit sector. These are then rented out to individuals at more affordable rates. There is also the possibility of co-ownership. Having tenants co-own the shared spaces can encourage and foster a strong sense of community. By involving the non-profit sector (as opposed to a private developer), it ensures that the goal of such residential co-operatives is social or public benefit, rather than generating profit.

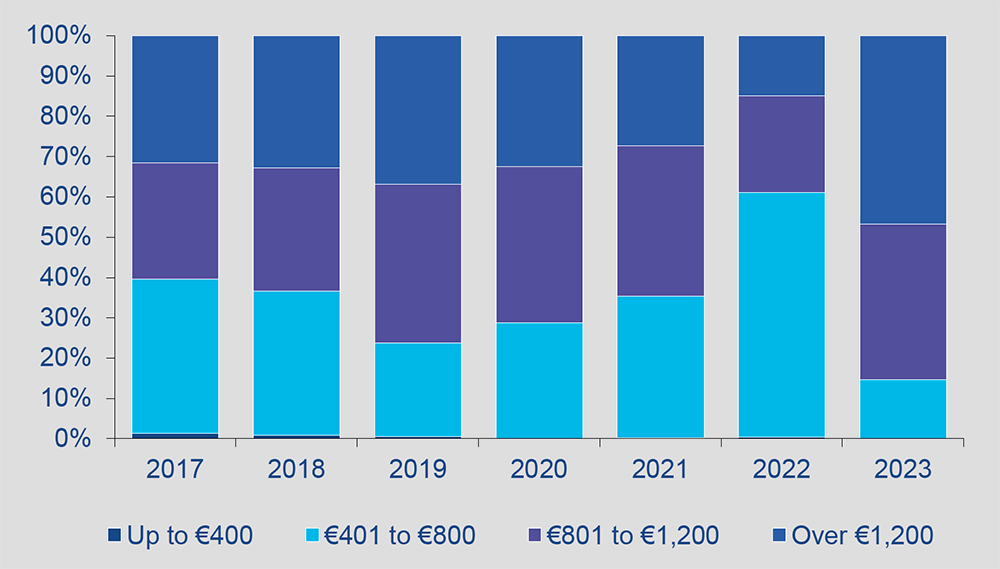

Another option worth considering is implementing a similiar policy to the UK’s Section 106 of the Town Country Planning Act 1990. Essentially this Act obliges developers to include a certain proportion of affordable housing in new developments. While the exact percentage differs according to region, the goal is to use developer contributions to keep properties available for people with lower incomes. This is especially pertinent when taking a closer look at the local rental market and the shortage of affordable housing. KPMG’s MDA Construction Industry and Property Market Report 2023 highlights how overall rental rates are increasing. Apartments with a monthly rent of up to €400, which made up less than 5% of the rental market in 2017, are practically non-existent in 2023. Apartments with a monthly rent of between €401 to €800 have also decreased since 2022, while those with rents from €801 to €1,200 and over €1,200 have increased. The figure below illustrates not only the composition of the local rental market by rate per month but also the drastic change from 2022 to 2023. According to the report this may be attributed to the ongoing shortage of residential properties for rent in comparison to the demand.

Source: KPMG Analysis

During our interview, Fsadni mentioned an idea he had discussed with colleagues. He makes it clear that this idea has not been tested at all, but merely discussed. It starts by trying to tackle the issue of putting the elderly in elderly homes. However, rather than putting the elderly in homes or large council estates, complexes are created that would feature bedrooms and bathrooms for residents but no kitchens. Instead, food is prepared by a cafeteria, catering for allergies and nutritional needs. By doing so, the state is investing in community health by ensuring that people eat well. This idea could also be expanded by having the complexes open to younger generations. In such a way, you are creating a strong, intergenerational community, while simultaneously addressing the issue of parents needing to come home and cook, for example.

‘I would be surprised if it worked without any significant revision after A/B testing,’ explains Fsadni, ‘but there is certainly room for imaginative policy development that can creatively address other problems too. What you need is lateral thinking sessions between experts and professionals, and experiment accordingly.’

Problems such as housing are complex as they are an integral part of a broader web of interdependent socioeconomic factors. One cannot attempt to address housing issues without considering the surrounding area, for example. How can the surrounding area be developed to improve the quality of life for residents?

If you’re trying to find an apartment or your forever home, you are experiencing first-hand the struggles of the local housing market. While the current system is a nightmare to navigate, the one silver lining is that there are alternatives. Unfortunately, until policymakers decide to seriously engage in some creative problem-solving, you might want to consider Frank’s suggestion – or find an easier way to live with your parents.

Comments are closed for this article!