We all agree that traffic can be exhausting. But it can also simply be exhaust. Vehicle exhaust emissions originate from their tailpipes and have been strongly regulated to tackle emissions of air pollutants. However, Maltese researchers recently found that this type of emission is not the major contributor to particulate emissions from vehicles. THINK takes a closer look under the hood.

Transport-related air pollution has an adverse effect on public health. Current policies have been addressing this problem, aiming to improve air quality by decreasing concentrations of transport-related pollution.

To date, only contaminants which originate from vehicles’ tailpipes – also known as vehicle exhaust emissions – have been regulated. The increased use of electric cars will lead to decreased emissions of pollutants such as carbon monoxide, benzene, and nitrogen oxides. While we can breathe a collective sigh of relief, exhaust emissions are not the only culprits that need to be tackled, nor are they the worst.

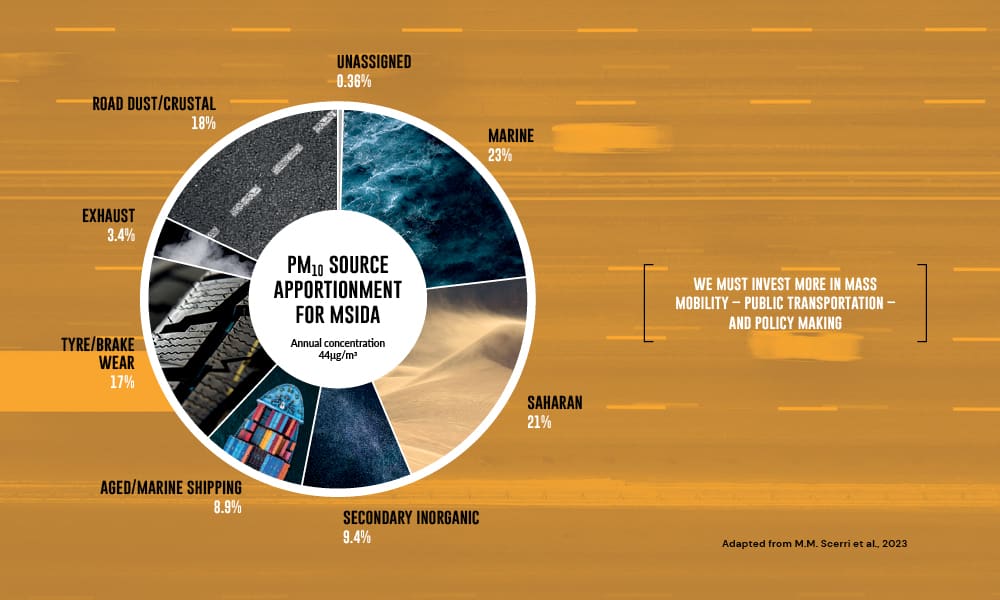

‘Shifting to electric cars will only solve the exhaust part of particulate matter from road traffic. We still face a major problem regarding other sources of particulate matter,’ highlights Dr Mark Scerri, lecturer at University of Malta’s Institute of Earth Systems. In a recent study, local researchers demonstrated that for Msida (a town in the Central Region of Malta), traffic-generated particles are the main pollution source to be considered (38.4% of total emissions). However, only 3.4% of traffic-related particles were due to exhaust emissions. The remaining 35% were due to road dust, tyres, and brakes. These are collectively known as non-exhaust emissions. These non-exhaust emissions constitute 87% of yearly traffic-generated particles and are considered detrimental to public health in particular. But what do we really know about non-exhaust emissions?

Non-Exhaust Emissions

To understand which sources could be contributing to emissions, the researchers collected data at an Msida traffic site with a sampler over the course of a year. The particles were subsequently analysed chemically in a lab, allowing researchers to identify the source of these particles. Interestingly enough, a portion of these particles came from natural sources, such as sea salt and Saharan dust. ‘A logical contributor since we live on an island near to North Africa,’ laughs Scerri. However, the most surprising result was that the bulk of traffic-generated pollution was not released from exhaust pipes, but from non-exhaust emissions.

Non exhaust emissions are caused by friction between the tyre and the road surface, the resuspension of dust particles previously deposited on the road, and the abrasion between the brake pad and the wheel.

These emissions consist of particles suspended in the air, also known as suspended particulate matter (PM). Particles with a diameter of approximately 10 micrometres (microns) or smaller are referred to as PM10, while particles with a diameter of approximately 2.5 microns or smaller are PM2.5. To put this into perspective, a human hair is around 70 microns wide. Both types of particles are small enough to penetrate deep into the respiratory system, aggravating symptoms of asthma or even leading to lung cancer. Contrary to PM10, PM2.5 levels in Malta have decreased over time. ‘It seems a small detail, but we have to remember that the longer we are exposed to these emissions, the worse the outcome will be,’ reinforces Scerri.

Impact on Policy-Making

While electric cars do reduce exhaust emissions, they still cause non-exhaust emissions through tyre erosion, road particle resuspensions, and brake-pad abrasion. Since these are not effectively regulated, the change to electric cars will not have a major effect on PM10 levels in the environment. In fact, by carrying a rechargeable battery to provide energy, the electric vehicles’ additional weight could provoke equal or higher PM10 emissions than conventional cars.

‘We are not saying that we shouldn’t change to electrical vehicles. We do believe that the use of electric vehicles should be considered, but as part of a basket of measures to control the emission of harmful particles and gases into the atmosphere. However, both electric and non-electric vehicles are impacting our health,’ the researcher explains. ‘We must invest more in mass mobility – public transportation – and policy making.’

At the European level, discussions addressing non exhaust emissions and their proper regulation are ongoing. Considering the extreme difficulty in achieving this goal, it is crucial to understand transport demand and traffic activities; ambient air quality, exposure, and effects; as well as urban planning. This requires information from several research areas, often creating transdisciplinary studies and teams.

Decision-makers and risk managers often ask what is the significance of the various components of the pollution emitted by transport that produce adverse health effects? Identifying such components would help risk managers focus their efforts and enable a more forceful reduction of adverse effects on health. The elimination of lead from petrol is an example of this approach; it has resulted in a substantial reduction in exposure to lead and its harmful effects on the neuronal development of children.

As mentioned by the researchers to THINK magazine, risk-reduction measures should be extremely calculated, as they may inadvertently have both positive and negative effects. For example, reducing exhaust emissions by increasing the proportion of electric cars may lead to increased PM emissions.

By discovering that the bulk of traffic-generated pollution is due to non-exhaust emissions, local researchers have helped identify one of the main pollution sources related to traffic in Malta. Understanding which pollutants people are involuntarily exposed to is crucial in order to improve the effectiveness of further action. ‘That’s why science should play an important role in policy-making decisions on – amongst other issues – transport-related matters and in evaluating its benefits and costs to society,’ states Scerri.

Comments are closed for this article!