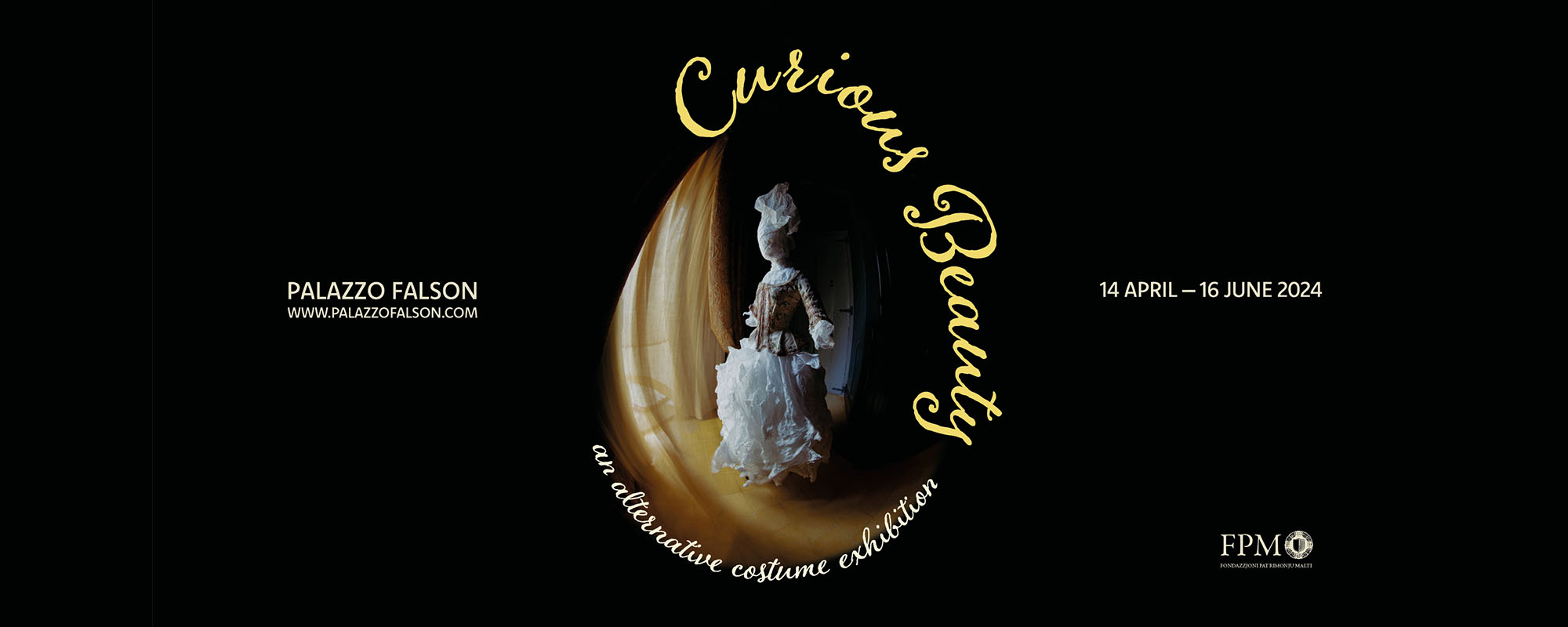

THINK had the opportunity to visit Palazzo Falson in Mdina to see an exhibition on historical costume and accessories as well as ecclesiastical mitres. This dazzling exhibition offers a glimpse into the fabulous fashion worn by the Maltese nobility throughout the 18th–20th centuries!

‘The University of Malta gave us the tools, and we built up from there. It gave us the background to be creative,’ Caroline Tonna and Francesca Balzan (Artistic Directors by Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti) warmly tell me before we start the Prosecco Tour of their exhibition Curious Beauty: An Alternative Costume Exhibition.

It’s the perfect window into their mindset to start off the tour. As artistic directors, Tonna and Balzan understand and respect the rules and conventional wisdom of curating a historical exhibition. However, they have used their know-how to playfully break the rules and present us with something unexpected. Tonna and Balzan, who both served as curators in the past at Palazzo Falson, were given free rein to put up an innovative exhibition in a museum that they know like the back of their hand. The self-imposed restraints were that the permanent exhibits at Palazzo Falson had to remain fully visible, and that they would display the temporary art installations of unique period costume and accessories in harmony with the set-up of the museum’s richly decorated rooms. Most of the objects on display have not been seen by the public before.

For months, they went through the collections of Heritage Malta, the Mdina Cathedral and Gozo Cathedral museums, and many private collections to unearth treasures, most of them from the 18th–20th centuries. The exhibition is a rare chance to see delicate pieces of clothing and accessories, usually stored away, brought to life and displayed with a bold, creative vision. The audience is given the opportunity to see skilled and detailed handiwork up close. We are trusted to appreciate the exhibition with respect because the pieces are literally within reach and not displayed behind glass cases.

Image courtesy of Lisa Attard

Threading the Past with the Present

At the start of the tour, while standing next to a resplendent Edwardian skirt and blouse set made entirely out of Maltese lace, Balzan delightedly explains the rarity of the ensemble. The Maltese lace has been delicately assembled on a bespoke Perspex mannequin and purposely lit up from the inside to further enhance the intricate lacework that may be examined closely by visitors. In fact, these beautifully crafted lace pieces were probably never worn. Instead, they were likely displayed as a bravura showpiece. After inspecting the handiwork on the Maltese cross and Festun tal-Istilla lace motifs, we are invited to continue the tour in the courtyard.

Tonna and Balzan wanted to have something displayed in the courtyard, even though displaying items outside, exposed to the elements, proved challenging. They came up with an ingenious solution: displaying a monumental star motif – inspired by the beauty of the Edwardian lace ensemble – in contemporary art. They asked Anna Maria Gatt, a skilled lacemaker, to make a huge Festun tal-Istilla in rope instead of thread, which they then mounted on the veranda framework to display against the cream of the Globigerina limestone.

Image courtesy of Lisa Attard

Observing how the rope snakes through multiple loops and complicated knots, only visible when looking at the pattern up close, I find a new appreciation of lacemakers’ skills. The art directors explained that the workspace took up the entire room, so Gatt needed to pin the ropes to the floor and reach for different ropes across the room to work. Usually, lacemakers start a pattern, and if the thread runs out, they simply tie a small knot to the new thread. With rope, it is impossible to make a small knot, so Gatt had to ensure that she had a long enough rope before starting a new section.

Hats Off

The exhibition continues to surprise and delight throughout. The pieces, displayed in conversation with each other, are not only shown as historical artefacts but also functional objects once used by people. The clothes and accessories become imbued with life and character, inviting us to imagine why the people who wore them picked these particular items: what they liked, what was chosen with taste, what pieces reflected their identity and status, what they could afford, and what was fashionable at the time.

Baroque and Rococo bodices and waistcoats stand around like a gossiping group at a ball. 18th Century gloves gesticulate at each other. Hats hanging from the ceiling hint at their wearers coming up the stairs in a jolly group: sombre ladies from the 1940s in evening wear, the summer hats of young women from the 1950s, scattered sailors, gentlemen in bowlers and felt, and even a Monsinjur’s biretta and saturno. The additional advantage of seeing hats displayed this way is that you can spy the labels on the inside. Some of them have their makers’ names, while others bear the names of their wearers. One example of the latter is the hat of Barone Giuseppe de Piro Gorugion, a noble gentleman whose headwear might have been connected to his uniform as a Knight of Malta from the Casa Rocca Collection.

Image courtesy of Lisa Attard

When I think of historical Maltese people, I think of farmers, fishermen, and other workers who lived in humble circumstances. A lot of them had difficult lives that revolved around the Catholic faith. They were often dependent on nature’s providence and entertained each other with cheaper amusements. They would never have laid hands on the objects displayed, except maybe to put them on their masters. While that was the majority of the Maltese population, the exhibition gives us a glimpse of Malta’s small bourgeois class. These people led lives full of art, beauty, and fun. They carried handbags covered in delicate feathers or made entirely of adorned metal. They wore elasticated shoes, like the ones that Queen Victoria favoured. They were well-connected and fashionable, importing the latest styles from Europe’s finest houses.

Meanwhile, the clergy were not to be outdone. A selection of exquisitely decorated mitres (a bishop’s ceremonial headwear) are displayed together to form an impression of a large mitre, clouded by the smell of incense for added atmosphere. Some of the mitres date back to the 1600s and are loaned from the collections of the Cathedrals of Malta and Gozo. One of the mitres is attributed to Augustus Pugin by Dr Mark Sagona. Pugin was an English architect and designer who pioneered the Gothic Revival style of architecture and was renowned for the interior design of the Palace of Westminster and Big Ben in London.

Images courtesy of Lisa Attard

Tonna and Balzan ‘broke’ another rule by deciding to display items non-chronologically. Their smiles as they explain how they put together items from different centuries reveal how much they enjoyed the process. The juxtaposition highlights how fashions have changed through time. This contrast was prominent at the corset display, where we could see how the structure of the corset changed to emphasise the breasts or hips in different centuries. The art directors decorated the corsets with feathers, conjuring images of powerful Amazonian women, challenging our view of the corset as a restrictive item. The women who wore these corsets had their own perspectives and might not have shared our modern opinion on the corset being a sign of oppression.

Creativity and Collaboration

The benefit of touring the exhibition with the directors is a new-found appreciation for their work. This is only possible by knowing the thoughts and the sheer number of decisions made when setting up an exhibition. Tonna and Balzan explain how they found an alternative to using expensive museum mannequins to display bodices and waistcoats. They used wrapped and folded acid-free paper, typically used to wrap clothing in storage, to imitate skirts and cravats and stuff the bodices and waistcoats. The acid-free paper was wrapped around regular mannequins bought from a clothes shop that was closing down. These mannequins were shaped, modified, and padded as necessary to fit the clothing. The result is truly eye-catching.

Tonna and Balzan are not stingy with praise for their collaborators. ‘In Malta, we have some truly talented people!’ says Balzan, while inviting us to admire the delicate work of ganutell (an artform of making delicate flowers from wire thread and beads), the flowers hand-made by Anna Balzan to adorn the epoch wigs skillfully made by Marcelle Genovese. As I am about to leave, we talk about collaborative work and how the best results often come from teamwork. Tonna and Balzan have been discussing this exhibition for two years now, and for many things, ‘we don’t even know who came up with the idea because we build on each other’s ideas.’

Image courtesy of Lisa Attard

Seeing this exhibition was a joy, and I learned more than a few things. I would recommend it to anyone, in particular the Prosecco Tour, not just for the bubbly, but for the wonderful insights that can only be provided by the artistic directors themselves. You are assured you will spend the evening in great company!

The exhibition is open every day except Mondays until 16 June at Palazzo Falson Historic House Museum, Mdina. Visit the webpages of Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti and Palazzo Falson for the dates of the next Prosecco Tour and other activities.

Comments are closed for this article!