Graziella Vella for the Valletta 2018 Foundation

A successfully regenerated area improves citizens’ quality of life by enhancing physical, social, and economic wellbeing. The process is similar to walking a tightrope, where positive impacts can easily cross over with negative outcomes.

Cities are using culture as a tool to regenerate themselves. Events are commonly used to generate impact. Large scale events, such as the Olympic Games and the European Capital of Culture (ECoC) have become a significant catalyst of urban change. In staging these events, considerable investment is required. The huge impact they need is not always sustainable if cities plan development exclusively for a single event and do not consider long-term impact.

The European Capital of Culture (ECoC) was originally created to celebrate established cultural cities, but has developed into an opportunity for cites to create urban, cultural and social regeneration. Today, ECoCs mainly focus on achieving the following: sustainable long-term development, urban regeneration, infrastructure development, social inclusion, and more visitors.

Recent ECoCs’ capital expenditure budgets from 2005 onwards range from €984 million in Liverpool to a €30 million in Essen (2010). Investing in cultural infrastructure is a prime objective, but this investment often lacks a long-term perspective. Many times, ECoCs end up with ‘white elephants’, infrastructure which is under-utilised or not utilised at all after the event.

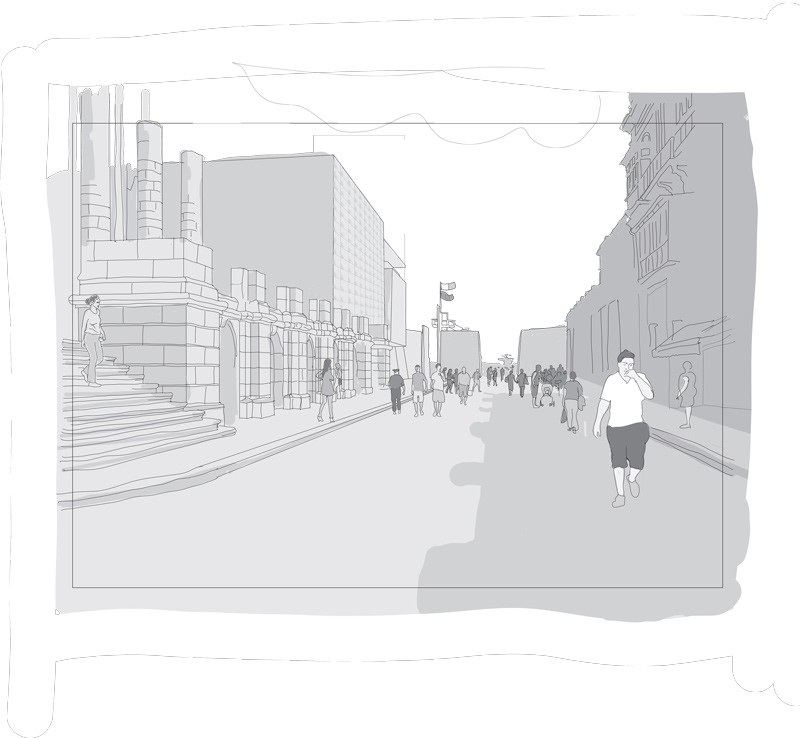

One of the most common types of infrastructure development is the construction of landmark buildings in decaying areas of a city. They attract increased visitor attention but can remove the element of creativity and innovation, which is an essential ECoC element. In contrast, the ‘Barcelona model’ takes a different approach. During the 1992 Olympic Games, Barcelona wanted to regenerate itself, using the games as a catalyst for urban change, transformation and renewal. Contrarary to other Spanish cities, like Bilbao with the Guggenheim Museum and Valencia with its City of Arts and Sciences, Barcelona did not choose to be associated with one building but looked at an overall picture of sustainable long-term investment, which 20 years later is still going strong.

ECoC cultural infrastructure development is not only about large-scale investment. The creative industries can be used to showcase the uniqueness of a city. The development of cultural quarters has often been used to regenerate cities and specific areas in a sustainable manner with a long-term vision. Urban regeneration can take place through the re-creation of a vibrant city space.

Culture should be integral to the vision for the regeneration of an area. A cultural infrastructure strategy that places culture-led regeneration at the centre of this strategy will give a city and its citizens what they really need after ECoC is over. Strategies include the re-use of existing buildings and local engagement to ensure full project ownership. It is vital to focus on developing human capacity in the Creative and Cultural Industries. Developing human capacity will make ECoC sustainable.

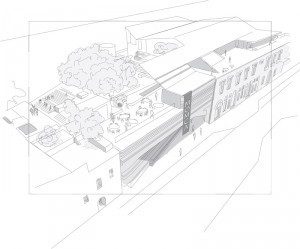

Malta’s capital city, Valletta has recently won the ECoC title for 2018. The bid, V.18, encompasses the whole of the Maltese Islands spreading investment, activities, and events throughout the whole territory. One of its most immediate concerns is the development of cultural infrastructure. V.18 has recommended a number of projects after a wide engagement process. These recommendations reflect the needs for Malta’s cultural and creative scene in the long term. Overall, one has to look at the importance of optimal governance and management to ensure that these projects are implemented in the best way possible. This is ultimately the challenge faced by V.18 and the Maltese Islands to ensure that 2018 leaves a long lasting legacy. The way Malta devises the road to 2018: the planning, management and coordination involved, will ultimately reflect how its citizens will feel on 1st January 2019.

This article has been adapted from a paper presented at the Vth University Network for the European Capitals of Culture (UNeECC) General Assembly and Conference in Antwerp (2011). UNeECC is an international non-profit association which works at fostering inter-university cooperation in former and future ECoCs. Since 2011, the University of Malta has been a member.

Find out more:

Ministry for Tourism, Culture and the Environment, 2011. National Cultural Policy,

www.maltaculture.com

Creative Economy Working Group, 2012. Draft Strategy for Malta’s Cultural and Creative and Industries,

www.creativemalta.gov.mt

Palmer, R. 2004. European Cities and Capitals of Culture: Part I and II. Brussels: Palmer/Rae Associates, http://ec.europa.eu

Richards, G. and Palmer, R. 2010. Eventful Cities: Cultural Management and Urban Revitalisation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Valletta 2018 Foundation, www.valletta2018.org

Comments are closed for this article!